Kyoto is known as Japan’s cultural capital for its abundance of temples, shrines and historical landmarks. Lesser known is the fact that it’s also a thriving hub for indie game development. Well embedded in this scene is Liam Edwards, creator and director of the upcoming golf-like adventure game Cursed to Golf. We recently chatted with him about his career in the industry and the increasing interest in video games over the last few years.

1. Tell us about yourself and your background in the video game industry.

I’m currently a game designer and game director at Chuhai Labs in Kyoto. Growing up, I played a lot of video games and have naturally always had an interest in them. I knew that I wanted to do something within this industry and originally went to study computer science at university, which I was terrible at. This was back in the mid-2000s where the indie game scene wasn’t a thing and the only way anyone could conceive working in games would be by going to work for a triple-A company like Nintendo or Playstation.

I started freelance writing about games and managed to get an internship at GameSpot in the UK. I learned a lot and was able to meet some really talented individuals there but I still had a desire to work directly on a game. Around this time, a friend of mine reached out to me about a quality assurance position at Rockstar Games. I did their interview, waited three months to be rejected and then miraculously got a call-back to start my first official job at a video games company.

2. How did you go from Rockstar Games to Kyoto?

I was working on Grand Theft Auto 5 when I started and I also went on to work on Grand Theft Auto Online, as well as the San Andreas and Vice City ports for mobile. But after four years of shipping GTA titles and the numerous DLCs (downloadable content), I really needed to take a break. I had ideas around prototyping my own games and making video game-related podcasts, plus I also wanted to explore Japan for longer than the two-week holidays I had taken in the past.

I ended up coming to Japan to teach English for a year which gave me a lot of freedom and time to pursue what I wanted while earning a bit of money. After deciding I would stay long-term, I began transitioning back into working with games. Having the podcast was really helpful for me to be introduced to people in the industry and I was eventually offered a job at Q Games, another indie game studio here in Kyoto.

3. The term ‘indie game’ gets thrown around a lot these days. What do you think makes a game indie?

It’s quite tricky to answer. Originally, I think it was a classification just to differentiate between the scales of budget that different game studios may have. The line gets blurred in some cases. Games like Hades and Spelunky are called indie but those games have full production teams, take several years to build and actually cost millions of dollars to make. There’s also the more traditional understanding of indie as in, independent developer. Chuhai Labs is a relatively small studio, but would we be considered indie in comparison to someone making games from their bedroom?

The real challenge comes when you’re marketing your game because you could be featured alongside huge games that have had way more investment and it’s hard to make the average gamer understand the difference in scale. Two games could both be sold for $20 but one has had the benefit of professional auditing, programmers and incredible talent working on it, while the other may receive negative feedback because it has less content or is less polished.

I wish we had a more unique classification to account for the range of different studios to set player expectations. But the general consensus seems to be that if you’re not a triple-A studio like Nintendo, Ubisoft or EA, then you’re probably indie.

4. Could you talk about the process of creating a game?

It varies from studio to studio. For a place like us, we’re a small operation and depending on the stage we’re at, our team can vary in size from six to 15 people. Almost everyone wears multiple hats,. That includes me. I’m the designer, director and I have to do project management work to ensure everyone is on track. It’s exciting because we get to try different things.

We make games in Unity, which is a real-time development platform that everyone has access to now. Our process is quite freeform. It can start with a concept for a game mechanic that one takes to the wider team. A programmer will then try to build it and we’ll test the prototype. If it’s fun and it works, we’ll figure out how it can fit into the game. Other studios that are larger may have a more streamlined pipeline where there’s a specific task and it gets passed along like an assembly line.

The perks of a smaller team are that we can spend less time worrying about the process. You don’t want to be too disruptive but this freeform approach does open us up to possibilities that we didn’t expect. Larger studios may go from the beginning to the end without even realizing if something is fun or not. And people are less likely to interject because there is such a rigorous schedule and process to adhere to.

5. What was the inspiration behind Cursed to Golf?

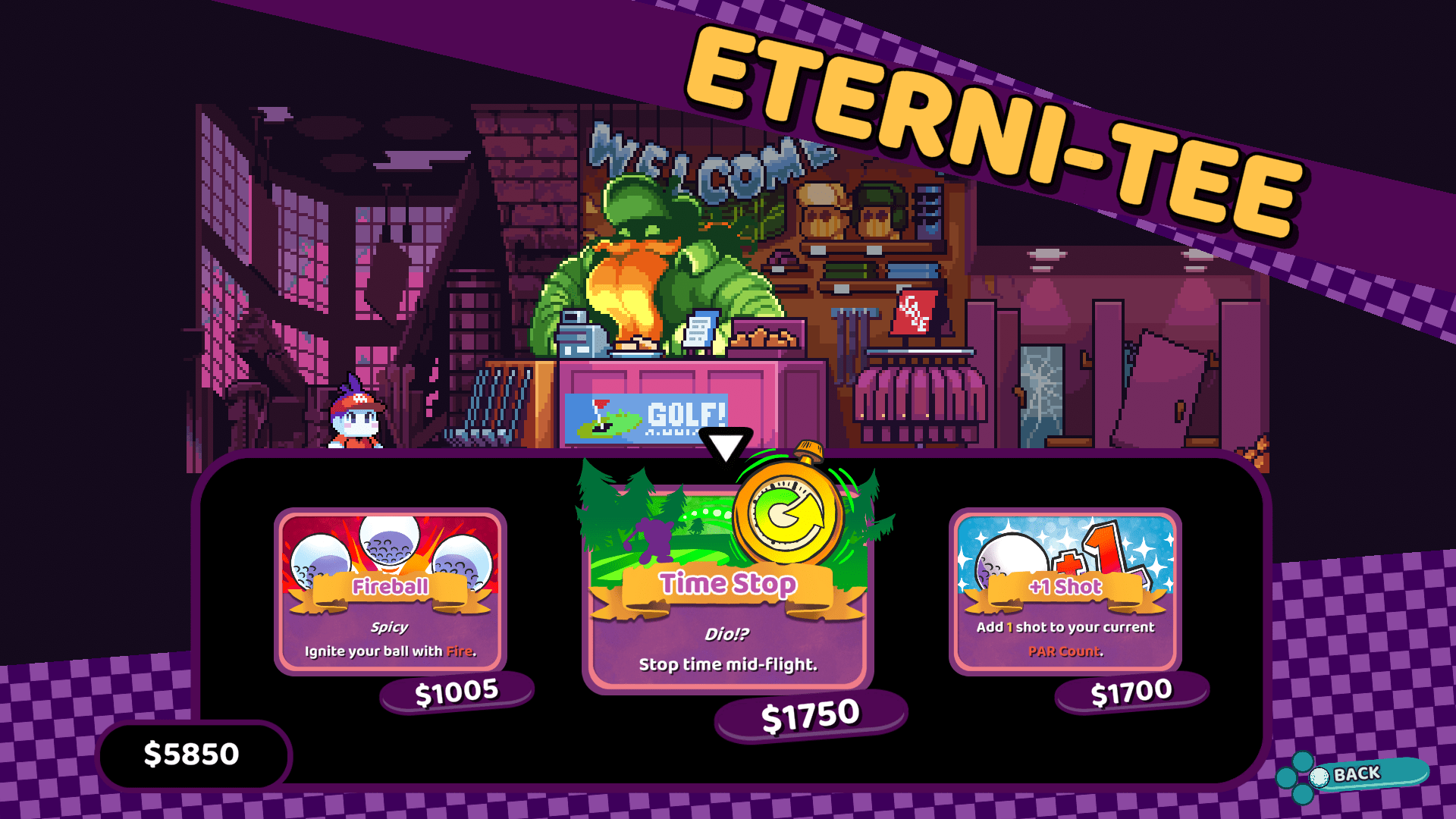

Cursed to Golf is based on a prototype I made myself last year in the middle of the pandemic. I was trying to think up interesting design ideas while listening to a podcast and came up with this concept of a rogue-like built around physics. I start with bouncing a ball around in a dungeon, which made me think of golf. Golf has a pretty long history in video games and I also saw parallels between hitting a ball in golf and combat movement in a game. All of this culminated into the first iteration of Cursed to Golf which I made in Game Maker and released on itch.io. Luckily, the game caught on and was shared on Twitter enough that it got noticed by a publisher. They reached out to me about creating a budgeted, larger-scale version of Cursed to Golf. This is what brought me to Chuhai Labs.

Because I’d already developed the first prototype, building the new version of Cursed to Golf has been relatively smooth as we have the ‘blueprints’ so to speak. We’ve not had to question things like how many levels or bosses or power-ups because we already have a good idea of what it needs. We’ve been very on top of our schedule and as a result, we’re able to scope it a little larger to include a compelling story and unique characters. A lot of people have played the demo and they’re surprised to know we only really started developing in January 2021. As we all know, 10 months in the video game world is nothing.

6. How has living in Japan influenced your career and creative direction with games?

I’m not a very sentimental person but sometimes I reflect on where I am and it’s like “Wow, I make games in Japan.” Not many people can say they do that. My boss Giles Goddard worked on games like Super Mario 64 and 1080 Snowboarding. It makes me think about what it must have been like for him to work here in the ’90s. Not only to be working for Nintendo but as one of the rare foreigners during a time period like that.

Even today, there aren’t many of us non-Japanese working on games in Japan. Here in Kyoto you’ve got studios like Chuhai Labs, Q Games, 17-Bit and Skeleton Crew. In Tokyo there are lots of localization companies who we all work with as well. It’s a great community where everyone knows each other and there’s a high level of professionalism. You’re constantly surrounded by talented and hard-working people who raise you up a little higher. It’s cheesy but true, when you’re playing with the best, they inspire you to be the best.

7. What do you think is the role of indie developers in the wider video game industry?

It’s not our responsibility to do so but we are able to experiment on ideas that bigger companies cannot take risks on. Some of the most interesting games in the world right now are indie games and it’s because they encourage players to think outside the box or explore what might seem like a stupid idea.

We get amazing games that take what might be a small aspect of a larger game, but they unpack it with great detail. Games like A Short Hike is simply about climbing a mountain. And it’s one of the most beautiful and wonderful experiences I’ve had in gaming. It’s condensed as well so the playtime is only two hours, but it’s two hours that will stay with me for a long time.

The other thing that indie games can show to people is that there is an accessible way to get into the industry. You can start right now on your own by searching for Unity, Game Maker or Unreal tutorials on YouTube to build your own games. You don’t have to go to school for it or to have lots of money to buy expensive equipment. Indie games have reduced the barrier to entry for video games as it’s now cheaper and easier to build and to play, in some cases they can even be free.

8. The Covid-19 pandemic led to a growth in video gaming. Do you think it’s a trend that’s here to stay?

I think the popularity of gaming will continue as it’s more accessible and no longer has the stigma of being a nerdy hobby. We have so many different types of gamers now, of different backgrounds and ethnicities. So, more games are being made for a broader audience. There are also different ways to experience gaming. Previously it had to be through buying a console but now lots of people are watching game streams on Twitch or jumping onto YouTube for reviews and walkthroughs.

Once you like games, you never really stop. You might go through a period of being really invested in a particular game, finishing it and then taking a break but sooner or later, you’ll be picking up another one and the cycle continues.

9. The video game industry has a reputation for having “crunch time,” often to the detriment of employees’ physical and mental health. How can the industry change to prevent this from happening?

I’m glad we are now in an era where people are shining a light on how video games are made. They are documenting the behind-the-scenes work which is really interesting in itself but with that, also highlighting the problems within the industry. These conversations have likely made it easier for game developers to raise their voices. They previously might have feared being blacklisted, may not have had an outlet, or the public might not understand what they’re going through. If someone talks about unfair working conditions today, there will be consequences from the public and we can hold companies accountable through social pressure.

Crunch, overwork and exploitation seem to happen more in triple-A companies. A lot of indie developers are actually people who’ve experienced this at big companies and gone indie because they don’t want to work under those conditions anymore. It’s what happens when there are these multi-million-dollar projects at stake that have to be delivered on time and there isn’t any thought given to how that affects the lives of people working on it.

Having worked at Rockstar, I learned a lot about what I don’t want to happen to my team. Now that I’m in a position where I can impact someone’s day-to-day work, it’s important to me to make sure they’re happy, have a good work-life balance and enjoy working with me. Hopefully more people get treated this way, go on to foster that in their future roles and we can see some more significant change in the industry.

10. Any advice you would like to give to those interested in a career in video games?

Just do it. Games are so accessible right now. There are game jams happening everywhere and it doesn’t matter if you’re a programmer, artist or project manager, there are so many ways to jump in. You’ll find hours and hours of content on YouTube that will teach you the rudimentary basics of how to make a game. Of course, persistence is needed but don’t overthink it. The first game you make probably isn’t going to be the one that you sell on Steam. Focus on making 100 small games instead and you’ll learn so many things and be able to start selling games or land yourself a job at a games company.