Over 30 years ago, the world-renowned choreographer Maurice Béjart made history with his groundbreaking piece The Kabuki, a two-act spectacle that combines two long-standing traditions: ballet and kabuki. Based on one of kabuki’s most important works, Kanadehon Chushingura, The Kabuki was exclusively created to be performed by the Tokyo Ballet, and it has become one of the most notable pieces in their repertoire.

Tokyo Ballet Revives Béjart’s Masterpiece “The Kabuki”

Though internationally famous, The Kabuki isn’t performed frequently — the Tokyo Ballet’s last international tour took place five years ago. This is because it’s an incredibly intricate production, with a significant number of dancers and complex choreography; the costumes and sets, too, are known for being elaborate and grand. But now, the show is back on home ground, with its first domestic performance in six years — the Tokyo Ballet will perform it three times at Tokyo Bunka Kaikan at Ueno in October. For those in Tokyo, it’s a rare chance to see an exquisite composition, known to be one of Béjart’s masterpieces.

“A show happens once and once only. Even with the same dancers, you never get the same show twice,” says Dan Tsukamoto, a principal at the Tokyo Ballet. He’s been portraying the dance’s lead, Yuranosuke, for 14 years, traveling all over the globe in the process. There’s something special, though, about returning to the place in which the piece originated and in which it’s set.

Revenge of the 47 Ronin

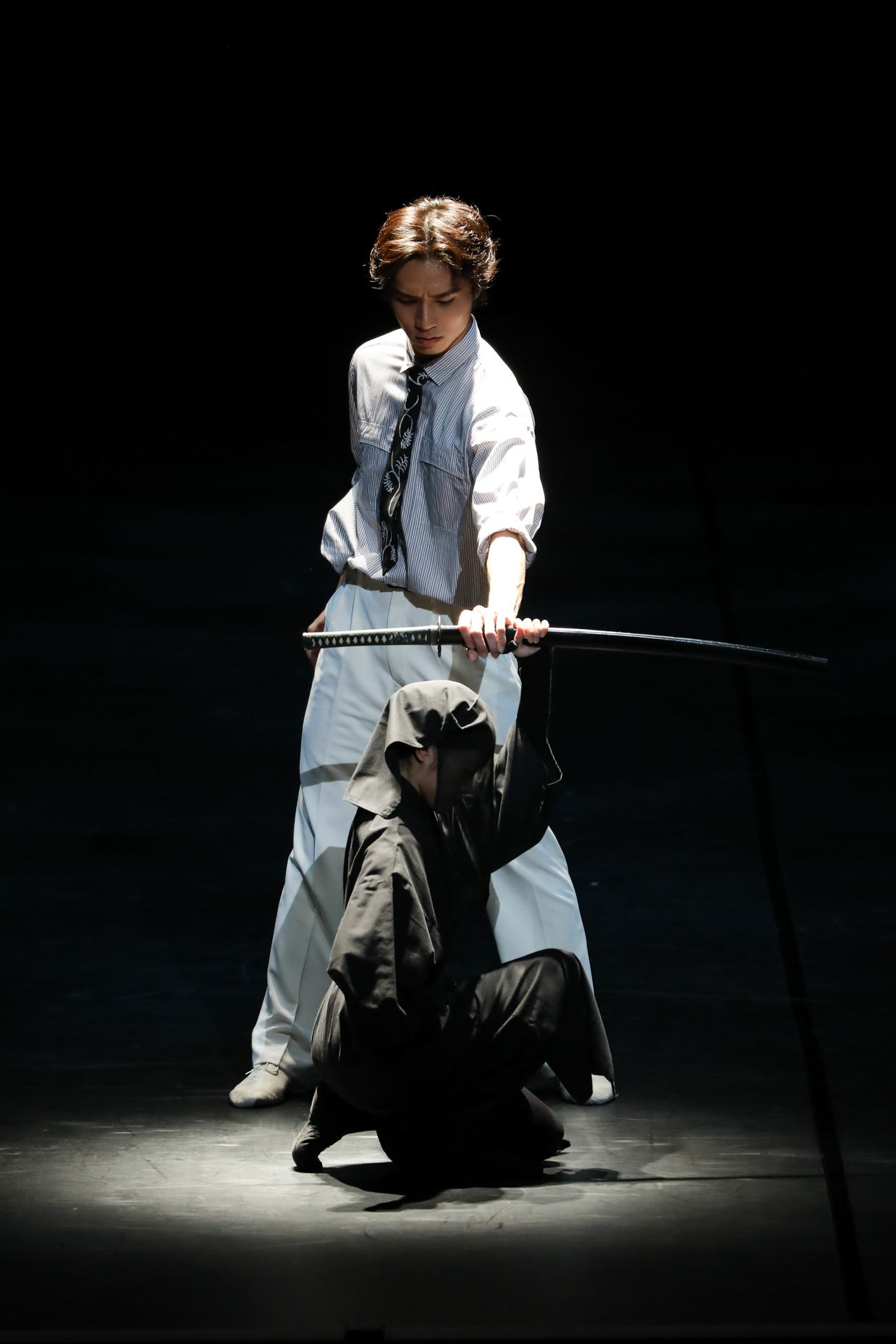

The story of The Kabuki centers on a young man who travels back in time to the setting of Kanadehon Chushingura, an incredibly popular kabuki play that was performed for the first time in 1749. Though fictional, Kanadehon Chushingura has its roots in reality: It’s based on the Ako incident of 1702, when 47 ronin (a word used to refer to a samurai without a lord) avenged their late master’s wrongful death, resulting in all of them having to commit seppuku. Béjart translated this incident into ballet, creating a powerful military sequence with an astonishing 47 male dancers on stage simultaneously.

“It’s rare to see male military dance at such a large scale in classical ballet, so I think it’ll leave quite an impression,” Tsukamoto says.

The Unlikely Marriage of Ballet and Kabuki

While creating The Kabuki, Béjart worked closely with composer Toshiro Mayuzumi and the Tokyo Ballet. And though its costuming, set design and gestures all heavily pull from traditional Japanese dance theater, The Kabuki still maintains its identity as a ballet.

The Kabuki’s choreography draws from nihon-buyo, a classical Japanese performing art that took inspiration from kabuki. In many ways, nihon-buyo and ballet seem polar opposites; ballet emphasizes fluidity, with movements that are meant to seem smooth and effortless, whereas nihon-buyo utilizes stylized and dramatic gestures and poses. “In ballet, you have to pull your center of gravity up, open your hip joints and imagine being as lean and long as possible, but in [nihon-buyo], it’s all the exact opposite, and you stay lower to the ground,” explains Tsukamoto.

However, this piece merges the two seamlessly, infusing the art of ballet with new power, perspective and possibility. “I had to learn movements and gestures that I wasn’t used to,” Tsukamoto notes. “Holding a fan properly, the way to hold the knife when conducting the seppuku or suri-ashi (sliding one’s feet on the ground) were movements I would never do in ballet.”

Leading the Troops

Tsukamoto, who was first selected to play Yuranosuke at only 20 years old, has been playing this role for nearly half his life. In many ways, Tsukamoto has grown with Yuranosuke, both professionally and emotionally. When he took on the role, he was one of the youngest members of the company. “At first I was surprised — I never thought I could get such a big role so early in my career, and to be chosen to perform the world-famous Béjart’s choreography that was made exclusively for the Tokyo Ballet was such an honor,” he says. “I was happy, but there was even more pressure on whether I could perform well or the audience would accept me.”

At first, he struggled with the leadership role. “I had no capacity to look at the people around me because I was at capacity just focusing on my own tasks,” he recalls. “I received advice from a senpai to work hard so I can lead by example, [so I took] the lead boldly, with my back to them.”

Fourteen years later, Tsukamoto has mastered the role of Yuranosuke, and become a brother-like figure in the Tokyo Ballet that his fellow dancers look up to. “Now, as a principal and mostly working with dancers younger than me, I’m able to pay attention to them. I take the lead, but I also dance in tandem with them to help them perform emotionally, as well as giving them a nudge if they need.”

In many ways, Tsukamoto’s growth parallels that of the character he plays. “Yuranosuke is not very strong at the beginning, but ultimately becomes confident enough to lead 46 men into battle. In performing Yuranosuke, I value his growth process, and I perform that in my acting — how I pause or deliver my gaze. The gaze of someone who’s insecure and confident is very different; it’s really detailed work, but I pay close attention to it.”

The Aesthetics of Limits

Tsukamoto is humble and may not outwardly say it, but Yuranosuke is an almost unimaginably difficult role that pushes the limits of a dancer. “At the end of the first act, Yuranosuke has a solo where he decides to go to war, but this solo is seven and a half minutes long,” Tsukamoto explains.

In classical ballet, even the longest of male solos are usually no more than three minutes, and even in contemporary productions, seven minutes is all but unheard of. Tsukamoto has his own theory of why Béjart decided to create a variation that was so physically taxing on the dancer. “Bejart’s works often have a theme of ‘the aesthetic of giving it all out and being at one’s limit.’ I entered the Tokyo Ballet after Béjart had already passed away, so I’ve never had the opportunity to meet him, but in those seven and a half minutes, I experience the limits of a dancer, as well as the beauty and strength that’s found there.”

Come as You Are

The Kabuki attracts a wide audience, including enthusiasts of history, traditional theater and classical ballet. However, Tsukamoto wants to reach guests who may be coming to the theater casually, too. “Some audiences new to ballet worry about whether they’ll understand the story, but I don’t really want people to do any review or studying before a performance,” he says. “I want audiences to experience the moment, even if their takeaway is simply, ‘That battle scene was powerful.’ It would be amazing if people’s interest in ballet could bloom from there.”

The Kabuki will be performed in Tokyo from October 12–14, and once in Osaka on October 18. Purchase tickets online at bit.ly/The-Kabuki.

Updated On August 30, 2024