I grew up in North London, and pride myself on my encyclopedic knowledge of the capital’s tubes and buses. Very much a city girl, I’d bet I could name an honorable portion of the city’s 272 tube stations and feel confident in my capacity to guide tourists to their most favorable shining red double-decker. But these worthless brags are, of course, just a cover-up for something I am embarrassed to admit: At the ripe old age of 25, I still can’t drive.

While this definitely hasn’t been a problem living in central Tokyo, one of the world’s best-connected cities, when I plotted a tour of the Kyushu countryside last year, the question of how I would navigate more remote terrain became pressing. On my student budget, the shinkansen was out of the question; the driver’s license-shaped hole in my wallet provided no way out. I was considering taking my whole journey by highway bus, when I remembered a book I had been given before I first moved to Japan, Hokkaido Highway Blues by Will Ferguson. I suddenly had an idea: I would hitchhike my way through Japan’s southwestern island.

Hitchhiking in Japan

This decision was met with some bemusement when I told my friends, who wondered whether hitchhiking in Japan was even possible. My ever-concerned mother expressed fears for my safety. While hitchhiking is technically legal in Japan, I was worried about its place in wider Japanese society, unsure of how the sight of a hopeful foreigner’s thumb on the side of the road might be received. But after hours scouring travel blogs and YouTube videos, I felt bolstered in my decisions. The incredibly low crime rates across the country certainly worked in my favor, and my (albeit loose) grip of the Japanese language would also be a plus. While anyone should proceed with caution before hopping into a stranger’s car, those who’d detailed their experiences online reported that they were met with kindness and a heavy dose of curiosity.

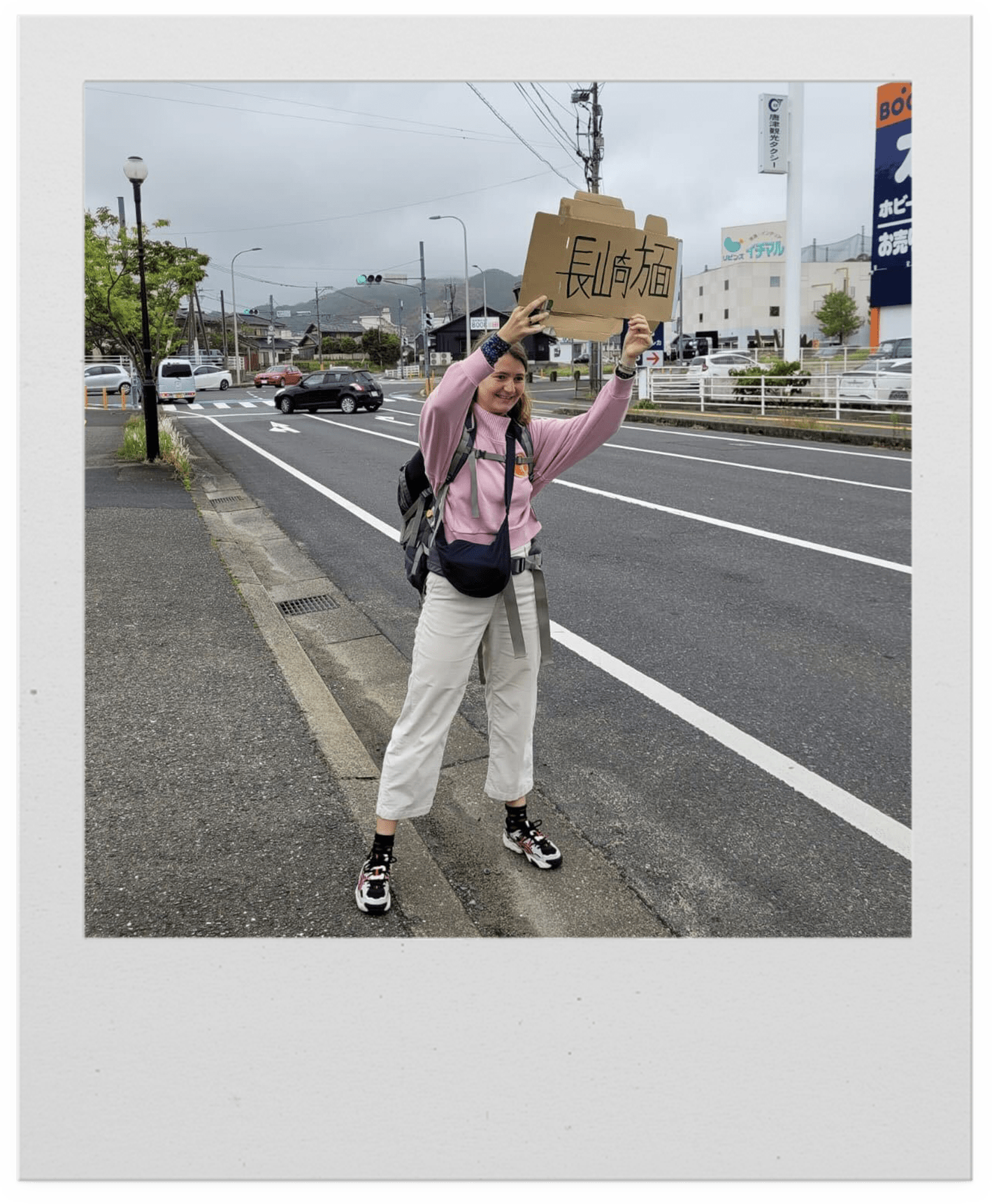

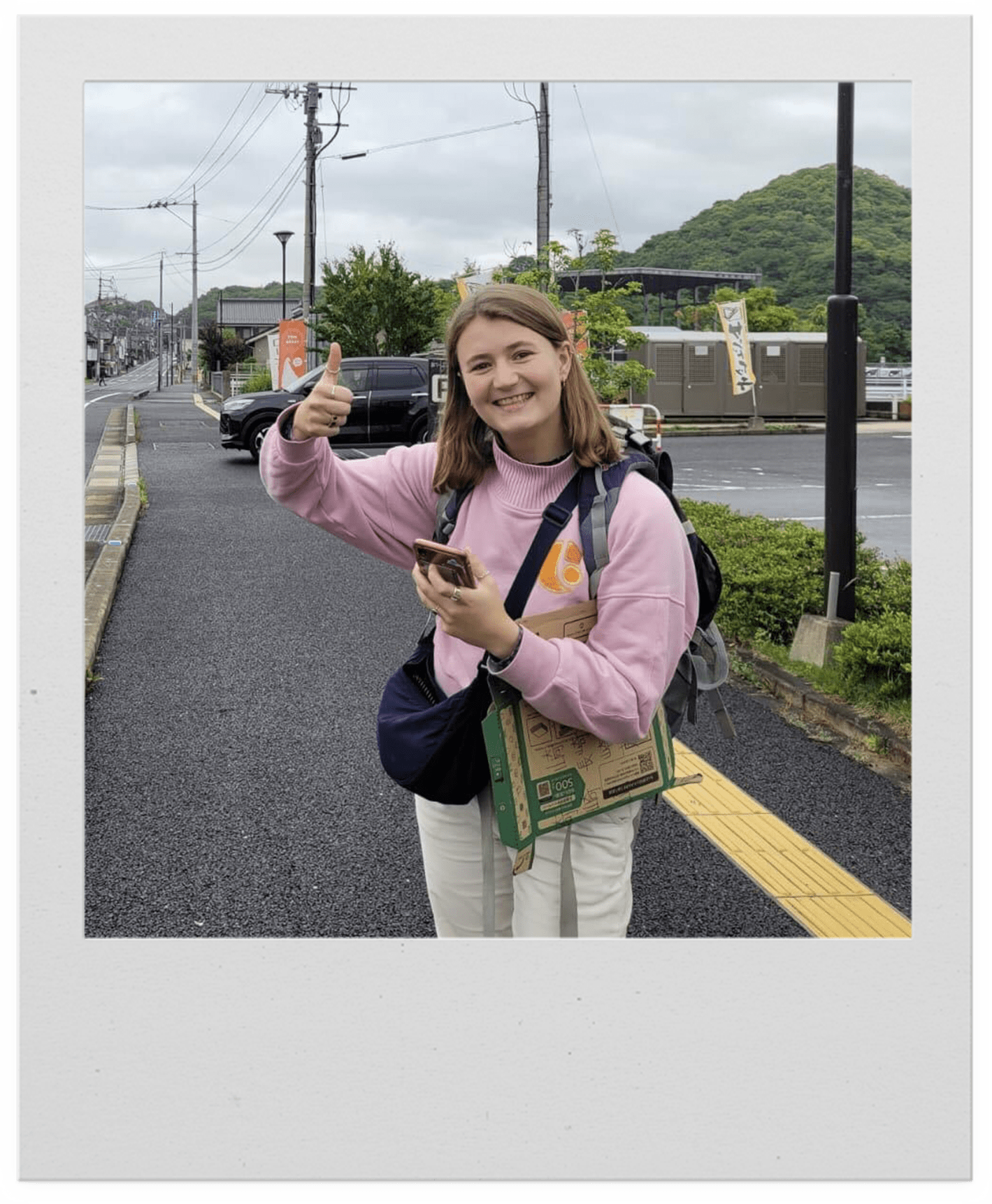

I flew from Tokyo to Fukuoka, and then caught a bus to Karatsu, a small pottery town on the northern coastline where I would begin my quest. Armed with some Tokyo omiyage as potential offerings, I stood on the side of the highway holding aloft a deconstructed Kirin box, on which I had gracelessly scrawled four kanji, loosely translating to: “The Direction of Nagasaki.”

During the first 15 minutes or so, I had absolutely no luck. I started to wonder whether my Karatsu hostel still had rooms for the night. After about 40 minutes, though, I caught the attention of two women about my age, one of whom was incredibly pregnant. Stopping the car beside me, they rolled down the window and offered me a lift further into Saga Prefecture. I eagerly accepted, and we spent the journey discussing potential baby names and Harry Potter, all of us gently giddy with the spontaneity of the encounter. When we said goodbye near a little town called Igaya, I resumed my posture at the side of the road, buoyed by the experience.

The next generous soul to scoop me up was an older lady about half my height. This driver seemed slightly calmer about the whole incident than my Karatsu friends; she told me later that she had picked up hitchhikers before, and enjoyed the company. As we wound our way through the Saga hills, I noticed the stacks of CDs spilling out of the car doors and asked her what kind of music she enjoyed. An enthusiastic conversation about jazz ensued, only briefly forestalled by my discovery that the name “Ella Fitzgerald” requires a careful attentiveness to each syllable in its katakana-ized form. We parted ways near Takeo Onsen.

Not far from my final destination now, the final leg of my journey from Takeo Onsen to Nagasaki was just an hour drive. Before long, a rather swish Mercedes pulled up beside me, with a young couple inside. They were headed out on a day trip to a nearby ashi-yu, and could give me a lift along the way.

Like everyone else who had generously stopped for me, they were friendly and inquisitive. Somewhere along the way I must have mispronounced the word for London considerably wrong, though; I found myself knee-deep in a conversation about the wonders of Italian cuisine as the Kyushu scenery flashed past, verdant and almost jungle-like. The couple deposited me not too far from the center of the city, where we took a selfie to commemorate the occasion. Even withstanding the wayward nature of the journey (and the significantly increased travel time), I felt oddly accomplished in what I had managed to do.

While it’s not the most conventional or efficient way to travel — and it certainly isn’t for everyone — there’s something about the mindset required for hitchhiking of which I’m particularly fond. Withstanding a certain degree of risk, hitchhiking is one of the best ways to interact with and learn a little about the local people of a place. Speaking to my various drivers, I got a real sense of the generosity of the Kyushu spirit, as well as the different ways people live. In fact, the whole experience has definitely accelerated my desire to get behind the wheel myself. It’s time to return the favor.

This article appeared in Kyushu Weekender 2024. To read the whole issue, click here.