Surveys related to sex and marriage in Japan have made quite a few headlines over the past few months. A recent poll taken by the Japan Family Planning Association (JFPA) revealed that 45% of women aged 16–24 “were not interested in or despised sexual contact,” while a questionnaire in Spa magazine showed that 33.5% out of almost 40,000 respondents thought that “marriage was pointless.” Hardly reassuring figures for a country facing a population crisis.

By Matthew Hernon

Last year Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Administration decided to act, assigning 3 billion yen for birthrate boosting programs that included marriage consultation and information as well as funds for local matchmaking events. It’s a proactive step which is encouraging, but will it really make a significant impact? Mariko Fujiwara—a research director and sociologist at Hakuhodo Institute of Life and Living—doesn’t think so. She believes both marriage rates and birthrates are decreasing because of various socioeconomic factors rather than a lack of opportunity for couples to meet.

“The whole notion of the government financially assisting konkatsu (marriage hunting) parties is absurd to me,” Fujiwara tells Weekender. “The main reason why fewer people are tying the knot these days is because of the prolonged recession and the increasing disparity among the young here in Japan. Between WWII and the 1980s people felt [like a part of the] middle class together because of a fairly successful redistribution of wealth: if you had a steady job you could expect a similar level of economic prosperity as your neighbor. This started to crumble in the nineties when the bubble burst and many companies went bankrupt. Since then the disparity between the rich and poor has been growing.

“For those in the lower economic strata, becoming financially stable is a difficult enough challenge when you are on your own; the prospect of then having to support a partner and kids seems impossible. Kindergarten, school and college fees can place huge financial demands on families. In a country like Japan, where people are quite prudent about planning for the future, many are choosing to forgo marriage altogether.

“It is a troubling situation that the government, in my opinion, has done little to aid. One of the main components of the 2015 tax reform package, for example, was a tax exempt scheme for presents of money—up to ¥10 million—from parents or grandparents to their adult children or grandchildren. That is fine if you have the money to begin with, but what about less-privileged families who have nothing to pass on? These are the people the government should be helping if they really want to see an increase in wedding ceremonies in this country.”

It is not just marriage rates that are falling, but also the number of people actually going out on dates. A growing number of young male adults are finding romance with characters like Rinko, Nene and Manaka on games like “Love Plus” for the Nintendo DS. Set in a Japanese high school, the game allows players to take their girlfriends on trips, give them expensive presents or even help with their homework. Whilst it may all sound like harmless fun, Chuo University Professor Masahiro Yamada is concerned that in many cases people “are being satisfied virtually,” and as a result don’t have the desire to find a real partner.

“It is no exaggeration to say that virtual romance is standing in for the real thing,” writes Yamada in his essay, “Japan’s Marriage Crisis and the Future for Young Singles.” Examples include the “JK” (joshi kosei, or high school girl) services, in which men pay expensive fees to enjoy a romantic walk with a female high school student. … Similarly, single women in their thirties and forties are often to be seen among the crowds of adoring fans swarming around the latest boy bands.”

Yamada, the man who coined vogue phrases like konkatsu and “parasite singles”—a single person living with their parents beyond their late twenties to enjoy a carefree life—believes the three main causes of the current crisis are “(1)the dwindling earning power of young men, (2) the persistence of the idea that a man should support his family financially; and (3) the maintenance of the norm according to which unmarried people continue to live with their parents.”

The three factors Yamada talks about are all closely related. In a survey carried out by the Cabinet Office in 2012, 43.9% of the female respondents agreed with the statement that “a man should go out to work while the woman looks after the home.” For many young females in Japan, bringing up children while continuing to work is not really an option. Revisions to the childcare leave law in 2010 helped—obliging companies to allow shorter working hours for women with children under the age of three—but childcare support for working mothers remains insufficient, meaning they have to give up on their careers after giving birth. A report by Goldman Sachs, titled “Womenomics 3.0: The Time is Now,” revealed that 70% of women in Japan leave the workforce after their first child, compared to around 30% in America.

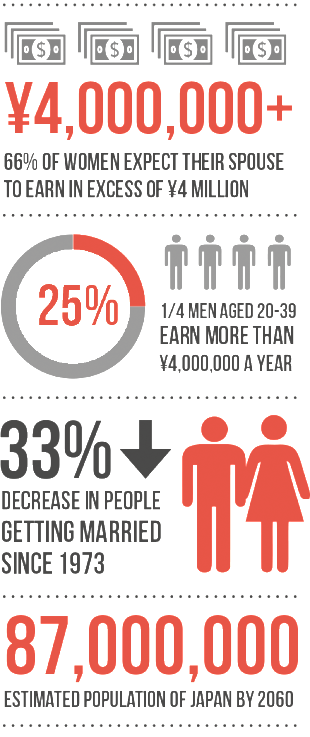

That puts extra financial pressure on the husband to earn enough to support the whole family. A poll by the Meiji Yasuda Institute of Life and Wellness revealed that two thirds of women expected their spouse to earn in excess of ¥4 million yearly. However, according to their findings, only a quarter of men aged 20–39 made that much. The consequences of this, according to Yamada, is that “many young men with poor economic prospects give up on the idea of finding a girlfriend altogether, while women continue to wait stubbornly for an attractive partner with a steady income.”

Yamada informs us that things started to change after the 1973 Gulf Oil crisis—when incomes began to stagnate. Back then, the annual number of weddings in Japan exceeded one million with a “crude marriage rate” (marriages per 1,000 people) of more than 10.0. In 2013 it stood at 5.3, with around 661,000 couples walking down the aisle. A massive drop certainly, but it’s not an anomaly. In the vast majority of OECD countries around the globe, crude marriage rates have fallen sharply over the past three or four decades and in many European countries like Spain, the United Kingdom, France, Germany the rate has been lower than 5.0 for the last few years. Just this month, Italian Health Minister Beatrice Lorenzin lamented low birthrates in her own nation, dubbing Italy a “dying country.”

The reason why people are more concerned about the situation in Japan is the alarming drop in fertility rates. In the aforementioned European countries, the proportion of births out of wedlock is usually somewhere between 30 and 50%; here it is around 2%. In 2014 the estimated number of newborns in Japan fell to 1.001 million—the lowest birthrate ever recorded in this country—while at the same time it has the world’s oldest population with a quarter of its citizens aged 65 and over. According to government estimates if current trends continue that percentage could well double by 2060, while the population will decrease to around 87 million.

That doesn’t necessarily forecast doom and gloom. As Nicholas Eberstadt—a demographer at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington DC—argues in New Scientist, “fewer people in the future will mean … [Japan] has more living space, more arable land per head, and a higher quality of life. Its demands on the planet for food and other resources will also lessen.” The conventional view, however, is a much bleaker one: a shrinking workforce will result in a huge drop in productivity; this in turn will lead to a decline in investment and savings, while the increasing number of retirees will put an ever bigger strain on the public pension and health systems.

It’s a vicious cycle: Japan’s economic downturn leads to fewer people settling down and having kids; fewer people settling down leads to even more economic misery. It’s a problem that all the match-making parties in the world won’t be able to fix.

What does the man who coined the word konkatsu have to suggest, as a possible way out? “We need to act now to break society’s attachment to the idea of clearly defined gender roles,” says Yamada. “We must get rid of the gulf in pay and benefits that exists between regular and non-regular employees, and cultivate a more tolerant attitude toward different types of families. Unless we act to implement these policies now, in a few decades’ time Japan risks becoming a nation of isolated and impoverished old people.”

Sources: 1.Population Statistics of Japan 2011, the National Institute of Population and Social Security research. 2. “Seikatsu Fukushi Kenkyu” No. 74, 2010, Meiji Yasuda Institute of Life and Wellness.