Japan’s next generation is saying no to study opportunities abroad, with the latest government figures telling us that after six continuous years of decline, the number of Japanese international students is at a 15-year low.

by Henry Watts

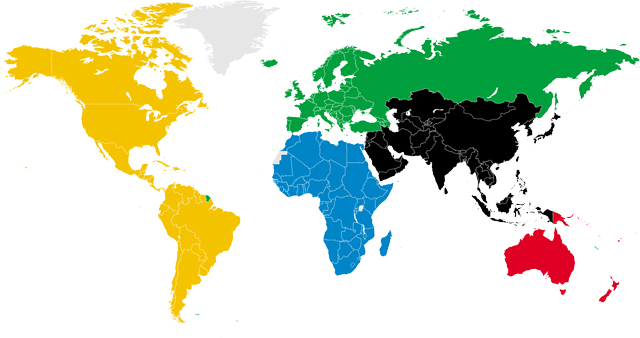

As China, Korea and India continue to lead global figures in cosmopolitan education, the situation in Japan raises concerns over a revival of its age-old reputation as an inward-facing nation. So, what is at the root of the problem?

There is a correlation, admittedly one that doesn’t prove causation, between the first year the so-called “yutori generation” reached university (2005) and the numbers of Japanese international students starting to decline.

The policy of Yutori Education, or “pressure-free education” was introduced in the 90s (and discontinued since), cutting school hours by 10% and the curriculum by 30% in order – it was hoped – to produce more well-rounded children who would be unsullied by academic rigour and competition. It even changed the value of pi in primary school textbooks to “about three”! Some commentators have blamed it for a drop in academic standards, as well as for its having produced unambitious and unmotivated students who, among other things, are less willing to test themselves in foreign environments.

Recent trends in employment could also be a factor. With companies turning increasingly away from more expensive, highly-protected, life-time employment (seishain) and towards cheaper, less-protected, contractual employment (keiyakushain), the stakes have been raised for Japanese students entering domestic job markets in the hope of securing sought after but scarcely available lifetime work.

This has arguably had the effect of turning studying abroad into something of an unwelcome distraction, especially when there is a lack of career support available to Japanese international students, and when “studying in an overseas university offers no benefit to job-hunting in Japan”, as a survey by Genron NPO, a policy think tank, found to be the second most common reason (46.2%) for the lack of interest.

It is true that studying abroad has not traditionally been considered an employable attribute in Japan, since Japanese companies have long preferred “blank canvas” new recruits who are easily moldable and trainable into the desired company image. Unlike the “ready-made labour force” that Americans, for example, present themselves as, Japanese students form, to borrow from author and anthropologist Chie Nakane, a “potential labour” force that relies on companies for tutelage but whose lack of experience is by no means a disadvantage.

The rich experience of studying abroad appears to offer little practical gain in Japan and thus justifying its price tag becomes a struggle.

Daiki Kumano, a business student at Rikkyo University, thinks conversely that there is plenty to be gained from studying abroad and enough appetite in the job market for students with such experience. He says, though, that the “traditional” character of his university actively discourages wander-lusting students like himself from studying abroad. “Senior professors said we should prioritize job-hunting … and take part in an internship program instead,” Daiki says. He has instead, though, opted to take his chances in Seattle.

The path to work in Japan is indeed very narrow and one-dimensional – precisely why study abroad students cannot get the support they need. Nanami Fukuda, who came back to Japan after studying for four years at a university in England, says she “felt left out of the system.”

“The job-hunting madness hit me when I came back,” she says. “It was like a culture shock. I was completely removed from the job-hunting process that everybody goes through at Japanese universities, and had to find a job on my own. And the longer I spent looking for a job, the more it looked to interviewers like I was doing nothing.”

Other paths to work may conceivably be forged when employers look to initiatives such the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and step up efforts to recruit young Japanese with international skills. Then, labour markets will liberalise and become more fluid, and job seekers, in the long run, will be forced to pitch themselves more as self-reliant ‘ready-made labour’ and less as moldable ‘potential labour’.

Efforts to globalize, such as those undertaken recently by Rakuten and Uniqlo (speaking English in the boardroom, for example), will seem rather cosmetic unless educational institutions overturn the kind of structural bias and marginalization that Daiki, Nanami and others like them have faced.

Aside from the obvious need for more access to information, more scholarships and more careers support for students, universities might also consider more forcefully bringing their academic calendars in line with most other countries and changing enrolment to autumn, as Tokyo University has half-achieved.

Above all, Japanese universities could really use a more robust liberal tradition – one that can break the inertia of the last several years and promote the rewards of study abroad.

A country is only as good as its young, and if that generation is inward looking, then so too must be the institutions that helped to shape it.

Updated On January 30, 2023