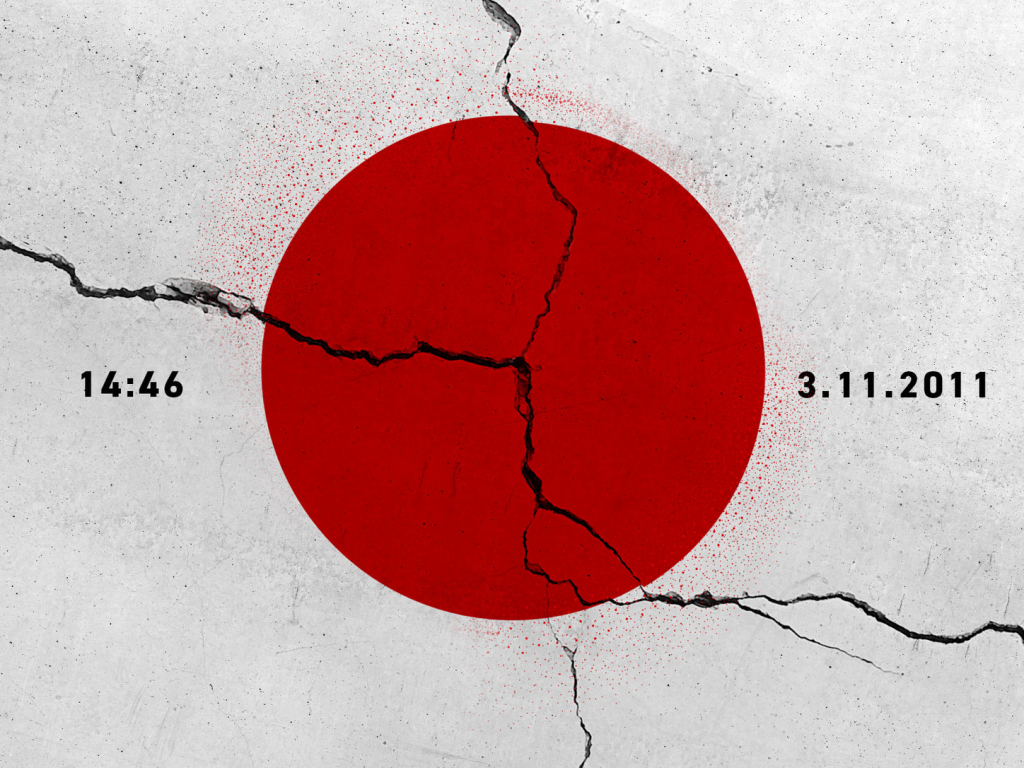

Thirteen years ago today, the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Japan struck off the northeast coast of Tohoku, 24 kilometers below the surface of the water. The ground started to shake at 2:46 p.m. on March 11, 2011, and lasted around six minutes, shifting the Earth’s figure axis by 17 centimeters, moving the island of Honshu more than two meters eastwards and shortening the length of a day by 1.8 microseconds.

The 9.0 tremblor triggered a devastating tsunami with run-up heights close to 40 meters. The waves, which reached as far away as Chile and caused large chunks of ice to break off from part of Antarctica, traveled inland 10 kilometers to Sendai. More than 1 million buildings were damaged with over 400,000 of them either half or totally destroyed. The estimated number of people who died or are missing is around 18,500, though some have the final death toll in excess of 20,000.

Heroic Acts Following the Tohoku Earthuake

As the water headed towards the small town of Minamisanriku in Miyagi Prefecture, 24-year-old Miki Endo called out over the community loudspeaker system warning locals of the imminent danger ahead. “A 6-meter tsunami is expected. It’s an abnormal tide, please go to a safe place.” She continued with the warnings for around 30 minutes until her boss said it was time to evacuate to the roof. Of the 40 people who tried to make it to the top, only 11 survived. Endo wasn’t one of them.

A posthumous national hero, she was credited with saving a huge number of lives. “She must have wanted to run away,” said Mieko Endo of her daughter who had only just married a few months earlier. “I wanted her to run away. I’m proud of what she did and who she was.” The skeletal remains of the local disaster management center where she and many of her colleagues continued working despite the risk will remain in the town as a memorial until 2031. Some feel it should be demolished as it brings back painful memories.

Like Endo, Motoko Mori had tied the knot a few months before the disaster and had told the principal at the school she worked at in Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture that she was preparing to have a baby. When the tsunami alert sounded, she first helped her own students evacuate and made sure they were okay before speeding off in her car to look for a group of swimming club members who were practicing at a pool on the coast around 500 meters away from the school. The huge wave overcame the embankment and swallowed the city. Tragically Onodera and the swimmers were never found.

As days and weeks passed a growing number of stories of individual heroism by mostly ordinary people continued to emerge from the tragedy, including that of Mitsuru Sato, a managing director at a seafood company in Onagawa, Miyagi Prefecture, who rushed to the aid of 20 Chinese students, leading them to a shrine on higher ground before returning to the affected area to look for his wife and daughter. He was last seen climbing to a roof to avoid the tsunami but was carried away by the water.

The Fukushima 50

The sacrifices made by people like Endo, Onodera and Sato, as well as countless others who risked their lives to save those in trouble, must never be forgotten. The same goes for the gallant actions of a group of employees at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant who put their lives on the line to prevent a nuclear meltdown. Reactors 1-4 at the plant proved robust seismically but were flooded by the tsunami which swept over the seawall. It led to a triple nuclear meltdown, three hydrogen explosions and the release of radioactive contaminants. The situation would have been much worse had it not been for those workers who kept going while surrounded by potentially deadly doses of radiation.

Those selfless and mostly anonymous individuals were labeled the “Fukushima 50” by the foreign media as they worked in shifts of 50, though the actual number eventually ran into the hundreds. Working 12 hours at a time, they survived off crackers and vegetable juice in the morning and rice in the evening as the high levels of contamination meant it was hard to get food to them. “My eyes are filling up with tears,” posted NamicoAoto on Twitter after discovering her father had volunteered for Fukushima duty despite being near retirement. “At home he doesn’t seem like someone who could handle big jobs… but today, I was really proud of him. And I pray for his safe return.”

The employees on site were asked to start injecting seawater into Reactor No.1 around 28 hours after the tsunami struck to keep it from overheating and going into meltdown. Masao Yoshida was the man overseeing the perilous operation. Just over 20 minutes after giving the command, Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) officials directed him to stop as they were concerned that the seawater would render the reactors commercially useless. Disobeying headquarters, Yoshida instructed the men to continue. His refusal to bow to pressure from above helped rescue Japan from what could have been a much bigger catastrophe.

Speaking to CNN in 2011, nuclear physicist Doctor Michio Kaku said that, “if they didn’t put that seawater in at the right moment, we would have lost Northern Japan. That’s how close we came to a national worldwide tragedy.” Yoshida, who died in 2013 after being diagnosed with esophageal cancer, was hailed as a hero for his actions. As were the plant workers, who were honored with the Prince of Asturias Award for Peace handed out by the Crown Prince of Spain. Tepco and the government, meanwhile, were seen as the villains of the piece.

The Aftermath

A report by Tepco on the disaster said there was no way they could have prepared for a 9.0 magnitude earthquake and the tsunami that followed. A government-commissioned study, however, concluded that a lack of preparedness for a disaster exacerbated the effects of the accident, stating that the electric power company had failed to “take precautionary measures in anticipation that a severe accident could be caused by a tsunami such as the one that hit… Neither did the regulatory authorities.” The 506-page document also said that there were delays in relaying information to the public, managers lacked knowledge of procedures in how to deal with emergencies and overall communication was poor.

In 2008 an in-house study by Tepco identified an immediate need to better protect the facility from flooding by seawater as a large tsunami could hit the complex. Despite the warning, officials felt it was an unlikely scenario and subsequently didn’t take the prediction seriously. Protection measures were shelved to avoid additional spending. In 2016 charges were filed against three former executives at the company for professional negligence resulting in death and injury of 44 patients whose health deteriorated following forced evacuations from a nearby hospital and nursing home. The decision to acquit the three men in 2019 angered many Fukushima residents.

An evacuation zone with a radius of 20 kilometers was announced in the days after the disaster. It led to the evacuation of around 154,000 citizens in total. Several towns including the co-hosts of the Daiichi Nuclear Plant, Futaba and Okuma, were abandoned, becoming homes to wild boards and packs of stray dogs. The town of Tomioka had one citizen at least. Naoto Matsumura, a fifth-generation rice farmer, returned to the no-go zone to feed pets and livestock left behind with supplies donated from support groups. He initially escaped with his family but was turned away from relatives for fear of contamination and then couldn’t get into evacuation camps as they were full up. Describing it as “a hassle,” he decided to head back.

“It was crazy at first,” said Matsumura in an interview with Vice. “No lights, no sound. The first week I was uneasy. It was too quiet. I’m used to it now, but the emotion I felt when I realized I was alone is indescribable. ‘Loneliness,’ doesn’t quite capture it. That was the toughest thing to get used to… In the beginning I was worried about getting cancer or leukemia in five to 10 years. Now I don’t worry. …. I was told I had the highest radiation level in Japan, but that I wouldn’t get sick for 30 or 40 years. I’ll be dead by then anyway.”

More Than a Decade On

The evacuation order was lifted for much of Tomioka in 2017. The station, which was washed away by the tsunami, was rebuilt with a shop and restaurant inside. Officials expected somewhere between 3,000 and 5,000 people to return within two years. As of June 1, 2023, the town has an estimated population of 1,326 in 5,578 households. That’s less than 10% of the population in 2011. It’s a similar situation in nearby areas such as Namie and Okuma.

Futaba, the last town to be completely off-limits since the disaster, opened its entrance gate in March 2020, allowing access to a space of around 2.4 square kilometers near the reopened train station. All of the approximately 7,000 residents were forced to leave the town following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. Currently, there are 102 people are living there as 85% of the town remains under evacuation orders On March 7, 2024, a local post office finally reopened after 13 years. A survey of over 1,400 households taken in 2019 revealed that only 10.5% wanted to go back home.

Over the past 10 years a huge effort has been made to rebuild the Tohoku region. Roads and other public infrastructure have been restored, buildings have been rebuilt and new industries have emerged. Due to weathering effects and the natural attenuation of radioactive cesium, radiation levels have dropped off significantly meaning the no-go zone currently occupies approximately 30% of what it was at its maximum. Despite this, the number of evacuees from the region is said to still be around 29,000.

According to Tepco, the process of decommissioning the crippled power plant is likely to go on until 2051, yet with so many technical difficulties, some feel that time frame may be too generous. In August of last year, Japan began releasing treated radioactive water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant into the sea. The controversial move was criticized by several groups, including local fishermen and neighboring countries. China was the most vocal of those critics, describing it as “an extremely selfish and irresponsible act.” Adding that it was like “passing on an open wound onto the future generations of humanity.”

In the 13 years since the Tohoku region was hit with what was a devastating triple disaster, great progress has been made yet for some, the nightmare is ongoing. A significant number are still unable to return home while several others, who are now allowed to go back, feel it’s not safe enough to do so or have already settled in a new location.

Related Posts

- How Photographer Mayumi Suzuki is Honoring Her Parents A Decade After March 11

- What to Do During an Earthquake in Japan

- More Earthquakes Expected in Chiba in Coming Days

Updated On March 11, 2024