This article appeared in Made in Japan Vol. 4.

To read the entire issue, click here.

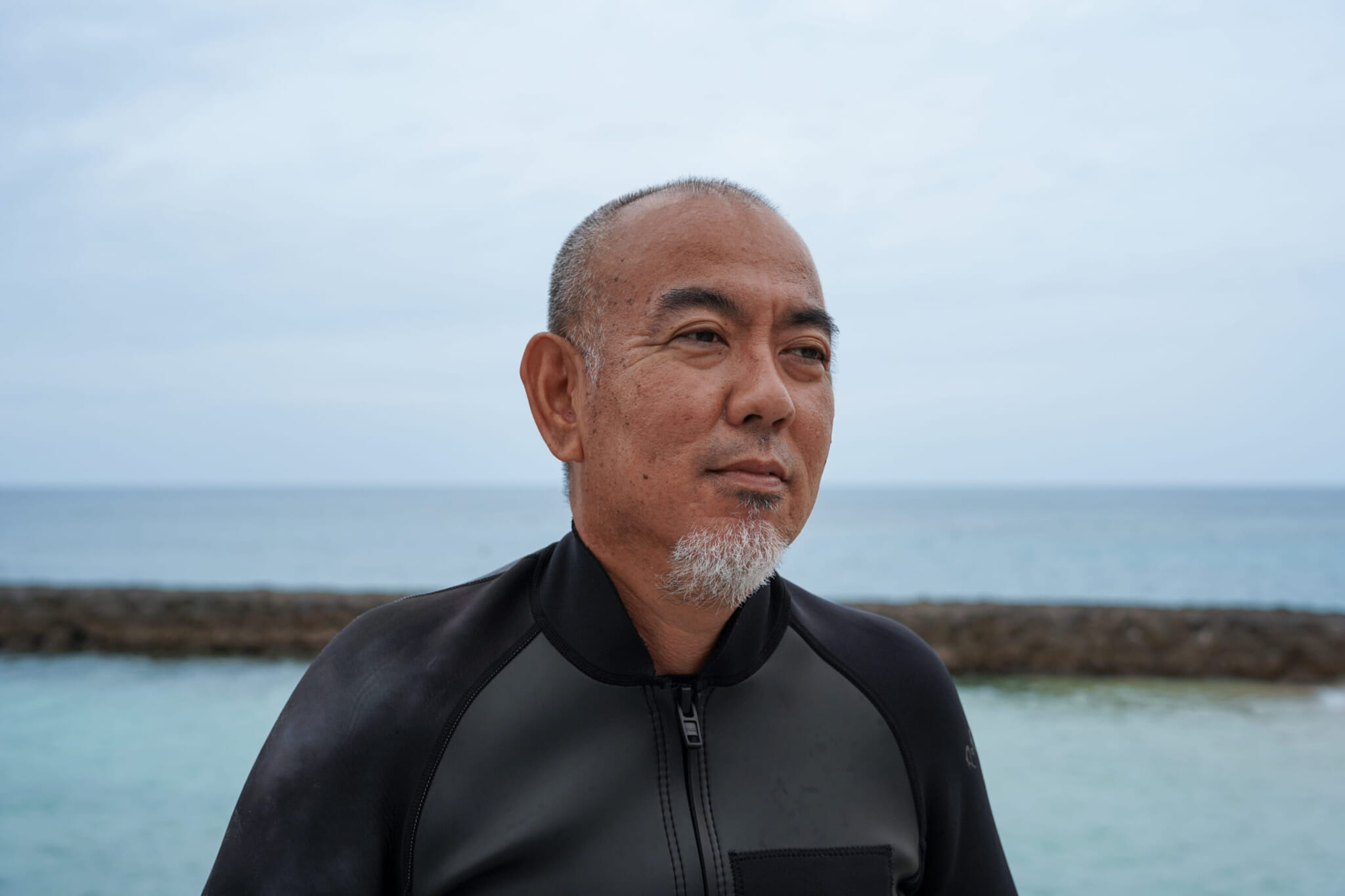

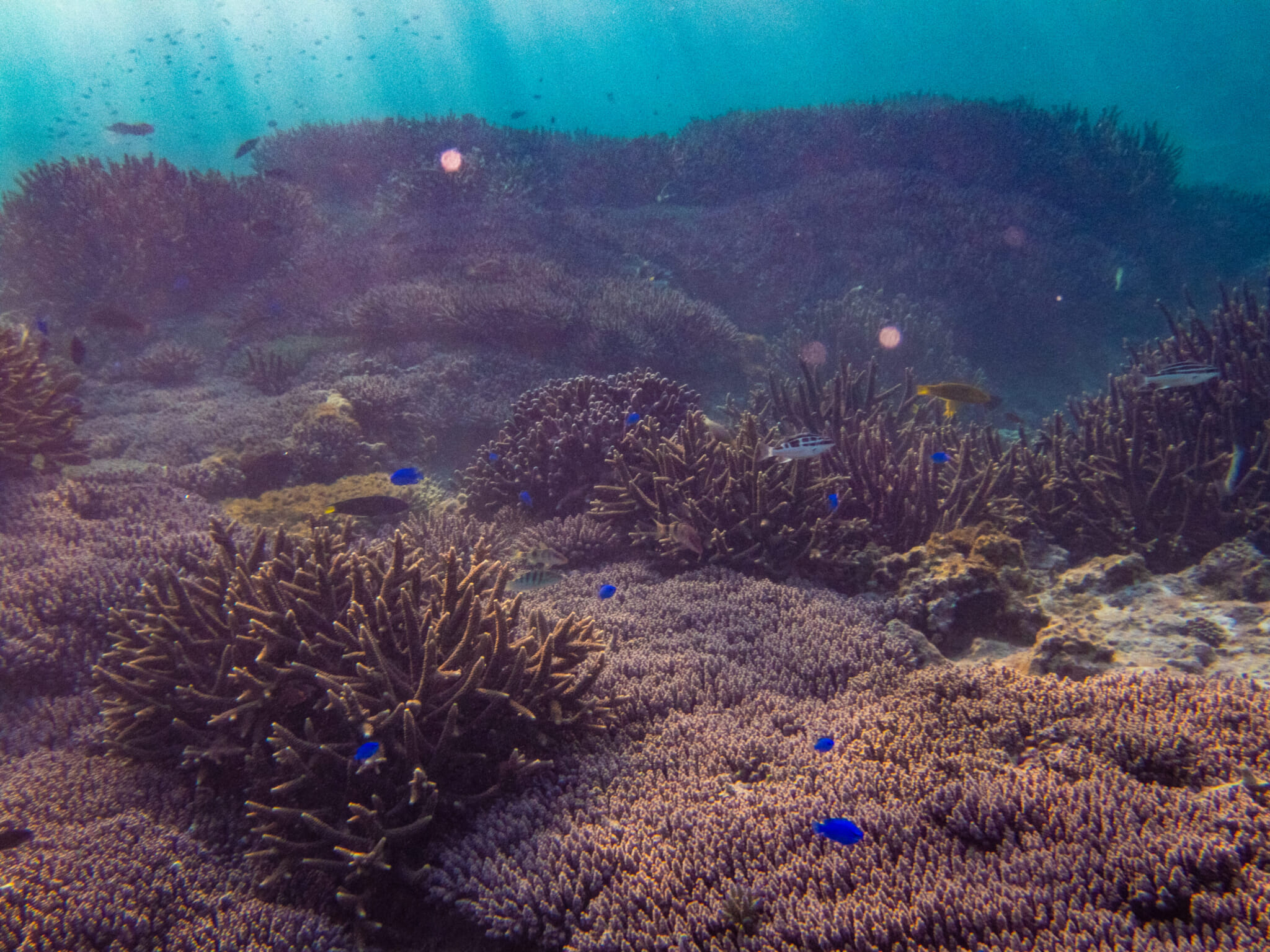

Each year, as spring bleeds into summer, a small universe is born in Yomitan, a village in central Okinawa. Under the full moon, corals commence their annual spawning, creating constellations of pale pink orbs in the dark ocean. As the reef prepares itself for another year, one man hauls a tank on his back and slips into the underwater galaxy to collect these budding coral eggs. The man’s name is Koji Kinjo, a Yomitan native and the patron of this reef, which was at the precipice of eradication over 25 years ago.

Years ago, Kinjo achieved something previously thought impossible: He transplanted coral that had been propagated on land back into the ocean — and, defying expectations, the coral continued to thrive and spawn in the sea. As the founder and director of the Sea Seed coral farm, he dedicates his life to this cause. Thanks to a special permit, he is able to collect coral samples from the wild, which are then cultivated in an aquarium until they reach a certain size. As of 2020, his organization says, they have successfully planted over 150,000 coral plants in the ocean floor.

An All-In Gamble on Okinawa’s Coral

Sea Seed’s work is increasingly vital: Coral reefs are known to have the highest biodiversity of all the marine ecosystems in the world, and Okinawa is one of the world’s most coral-rich regions. Now, however, many of the island’s reefs are under existential threat. This devastation has been occurring for decades, the result of several interlocking and human-caused factors like overfishing, pollution and climate change.

It was a particularly hot summer in 1998 that first inspired Kinjo to act; that year’s scorching heat killed 90% of Okinawa’s coral reefs in a mass bleaching incident. Devastated to see the coral turned ghastly white, Kinjo made the life-changing decision to sell off his businesses and devote his life to saving the colorful ocean that he’d been raised alongside.

“It was hard to make people understand what I was doing,” Kinjo recalls. “People doubted my efforts, and if anything were worried that taking coral out of the water was doing more harm than good. They thought, ‘He’s saying he wants to protect corals but I bet he just wants to make money.’ A lot of specialists actually critiqued me, and I had to have a lot of conversations to get them to understand my logic.”

After years of trial and error, Kinjo had racked up debt and struggled to produce the results that would prove his critics wrong. But he was fueled by his unwavering conviction that what he was doing would be fruitful. “I didn’t want people to look down on me. I kept telling myself that what I was doing was not wrong,” he says.

Then, in 2005, the impossible occurred: Kinjo’s coral, which had survived transplantation in 2003, spawned eggs. “I felt like I could overturn all the doubt and criticism I’d received. I was so moved.” Kinjo became an overnight sensation and local hero; in 2007, he was the recipient of both the Environment Minister’s Prize and Prime Minister’s Award, a recognition of the incredible importance of his work.

Breakthrough in Survival

Kinjo’s success was a result of carefully studying coral for years. “I first raised coral to give it as little stress as possible, but it didn’t survive well in the ocean,” he explains. Coddling the colorful invertebrates, he found, left them ill-equipped for life in the sea. “I realized that coral raised under stress survives in the wild better, so I treated it to withstand extra light and low-sodium water.”

This technique yielded a surprising realization: Kinjo found that coral cultivated in stressful conditions is more likely to survive in high temperatures. “In 2013, there was a coral bleaching incident, and we realized that these coral raised under duress survived when other coral around it didn’t,” he explains. “As an experiment, we put two differently treated corals side by side, and as we predicted, in 2017, when we experienced another coral bleaching event, the coral raised under stress survived. This is when we proved that we succeeded in creating stress-resistant coral.”

This has promising implications for the continued survival of coral in an ever-warming ocean, but Kinjo warns against being too immediately optimistic. Though his findings are heartening, they’re not yet widely known, especially on an international scale. “There are more people and institutions now who want to transplant this stronger coral globally,” he says, “but when I look up initiatives happening now, I realize people are doing things that I did 20 years ago, that I know won’t work. I wish there was some kind of documentation of the newest advancement in coral transplanting that people can access and learn from my mistakes.”

Sea Seed coral farm

Additionally, the conditions in the ocean are worsening at an alarmingly rapid rate, and corals face threats on multiple fronts. “Water pollution can be more serious than rising sea temperatures in some areas,” Kinjo says. “Coral can revive from high water temperatures, but if the water quality is bad at the same time, the coral won’t survive. The stress that agriculture adds to ocean waters is particularly impactful. When it rains, all the fertilizer and pesticides from land drain into the sea; it limits the ocean’s potential.”

If conditions don’t change, Kinjo is convinced that coral populations could be completely decimated in just three decades. “It might be hard to believe that in 20 years something that awful could happen,” he notes, “but 30 years ago, Okinawa was full of coral. If we think about how much coral we’ve lost in the past few decades, it’s not hard to imagine that in 30 years all coral could be gone.”

This would be a devastating loss not just to the seas but to human civilization as well. Coral reefs are home to over 25% of marine life, providing food to billions of people. They also have a crucial environmental role, acting as natural breakwaters to mitigate the impact of waves. “If coral were to disappear from the world, it means the entire ecology of the ocean has crumbled, so we won’t have any access to the ocean’s resources,” Kinjo warns.

Sea Seed coral farm

Resilient Revival

Despite the gravity of the current situation, Kinjo has never been one to lose hope. However, his outlook on coral survival is a little different from most people who work extensively with nature. “I don’t think it’s possible to go back to the ocean from the past,” he proclaims nonchalantly. “But I do believe we can create new technologies to plant coral where they’ve disappeared.”

Instead of holding on to a fantasy of returning to some kind of prelapsarian sea — where oceanic ecosystems thrive in the way they used to, before human contact — Kinjo is convinced we should take a more pragmatic approach. “I think it’s okay to have man-made nature,” he states. “It might sound violent, but humans have made so many things on Earth. I think it’s natural for humans to create things that other creatures will live in. We’ve already stolen so many homes; we shouldn’t get nervous about creating them.”

Kinjo also emphasizes that things aren’t at all hopeless — if that were the case, he wouldn’t be able to persevere. “No expert believed that we could get coral to spawn, that they would grow to be resistant against warmer ocean temperatures, but here we are,” he says emphatically. “As soon as we believed in the coral, they easily overcame the obstacles. Animals aren’t as fragile as we think. If we are optimistic about reviving coral, nature will meet us in the middle.”

Learn more about the efforts to rejuvenate the reefs of Okinawa at miraclecoral.org.

Related Posts

- How Responsible Travelers Can Contribute to Sustainable Islands

- Is It Possible to Live a Sustainable Lifestyle in Tokyo?

- How Climate Change Is Directly Affecting Japan

Updated On July 11, 2024