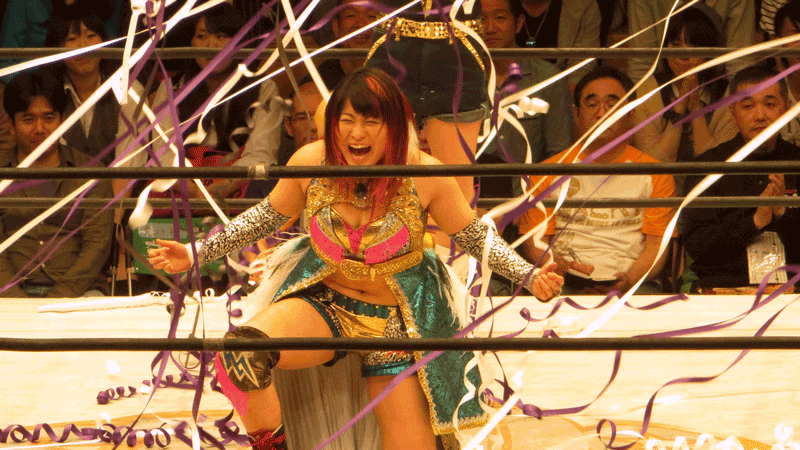

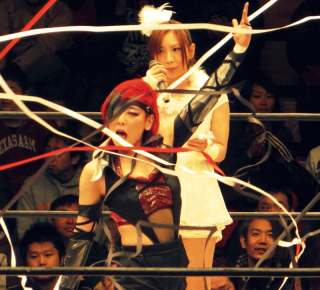

Getting up close and personal with the gorgeous ladies of joshi puroresu.

Text and images by Leslie Lee III

If you want to understand a few countries, watch their pro wrestling. In America you’ll see super-heroic musclemen—inexplicably portrayed as underdogs—defend the US against foreign behemoths. In Mexico there’s a similar battle of good versus evil, but instead of lone heroes, you find groups and multiple generations of families taking part in an endless struggle. In the twilight years of British wrestling you saw its aging stars slowly succumb to injury while its most promising youth failed to find glory outside the United Kingdom.

Like any great art, pro wrestling lays bare the myths a society is built on, the aspirations of its people, and the harsh realities that govern them all. The hopes and dreams of Japan’s schoolgirls created one of the most vibrant and influential forms of pro wrestling: it’s called joshi puroresu.

Japanese pro wrestling began as a post-war effort to reinvigorate the country’s wounded psyche. The legendary Rikidozan, who happened to be a Korean immigrant, wrestled to defend Japan’s honor against American grapplers in wildly popular bouts. When it was the ladies’ turn the same pattern was followed. Top US star Mildred Burke toured Japan in 1954; she and her cohorts staged more occupation-influenced drama for eager Japanese audiences. Joshi puroresu, literally “girl’s pro wrestling,” became an established form of performance art and All Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling (AJW) emerged as the pre-eminent joshi promotion.

The story of Japanese wrestlers overcoming the odds to defeat Americans, only to succumb to their dastardly tactics on the next show, repeated itself for the next decade. However, as the occupation faded into memory and Japan looked towards its future as a post-industrial world power, a new means of expressing Japanese pride was needed.

In the 1970s puroresu turned inwards and pitted Japanese wrestlers against other Japanese wrestlers. The art of puroresu advanced as more athletic wrestlers joined the fray. Wrestlers of this era put on complex matches that showed that wrestling could be exciting even without national pride at stake.

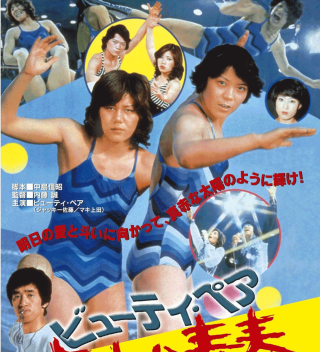

Jackie Sato and Maki Ueda, The Beauty Pair, dominated joshi in the late 70s. They became a genuine pop culture phenom: they had hit singles, won music awards, and starred in their own film. The Beauty Pair’s popularity garnered AJW a fantastic TV deal and brought in a rush of new fans, most of whom were teenage girls.

It’s easy to see why The Beauty Pair connected to the young Japanese women of that time. Sato and Ueda challenged suffocating gender norms: they were both beautiful and muscular; they were tomboyish and elegant; they were highly skilled athletes and platinum selling pop stars. They embodied the dreams of a generation of young Japanese women who saw a future that held more options for them.

As popular as the Beauty Pair was in the late 70s, The Crush Gals were even more so in the 80s. Chigusa Nagayo and Lioness Asuka had all the pop culture success of the Beauty Pair, but were also next-level athletes. The Crush Gals were tougher, meaner, and badder than their predecessors. Their enemies—The Atrocious Alliance of Dump Matsumoto, Bull Nakano, and Crane Yu—wore face paint and mohawks and carried weapons to the ring.

The story joshi puroresu told then was of strong, powerful, athletic good guys facing off against brutal, weapon-wielding cheaters: nice girls in the judo club versus the bad girls who smoked in the bathroom and bullied everyone. The good guys didn’t always come out ahead but the more the Crush Gals were beaten, the more fans loved them.

The art of pro wrestling is a violent one and careers are short. The Beauty Pair only existed for three years before Ueda was forced to retire due to injury, and Sato soon followed. AJW’s retirement age of 26 forced both Crush Gals to leave at the height of their popularity. The loss of the Crush Gals was especially damaging to joshi, as no later wrestlers became crossover stars on a similar level.

But as joshi lost some of its pop appeal, its legitimacy in the larger wrestling world grew. The late 80s and early 90s saw newer stars like Manami Toyota, Akira Hokuto, Aja Kong, Toshiyo Yamada, and Kyoko Inoue claw their way up the ranks in increasingly outstanding matches. AJW had multiple shows each year that drew tens of thousands of fans. They were so successful they even invited wrestlers from rival promotion groups to participate in their events.

The story was simple: joshi puroresu is the best. People took notice.

During this time joshi began to get international attention from die-hard wrestling fans. Male wrestlers began copying the innovative wrestling maneuvers of joshi. US wrestling companies flew over AJW stars. Joshi matches won Match of the Year awards and Manami Toyota was named the most outstanding wrestler, male or female, by Wrestling Observer magazine in 1995.

Like the Beauty Pair and Crush Gals booms beforehand, the pure wrestling-driven joshi high was short-lived. The faltering Japanese economy, the rise of mixed martial arts, and an aging and unhappy locker room caused AJW to splinter, dwindle, and eventually fold in 2005. Numerous other promotions opened and closed during this time period. Names like GAEA, ARSION, and JD*Star came and went with less and less fanfare in Japan.

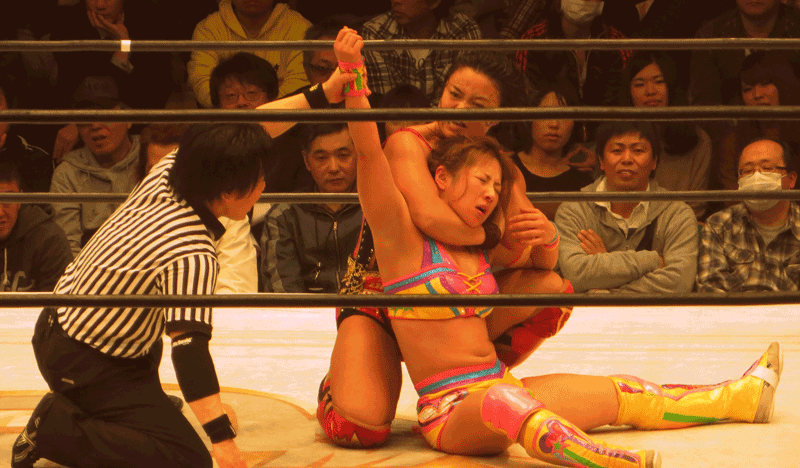

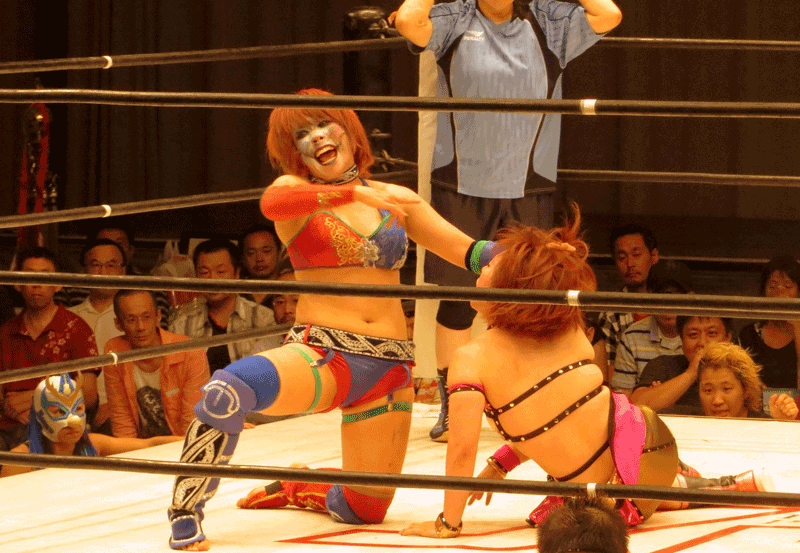

While joshi is nowhere near as popular as it was in the 80s, it has climbed out of the black hole that was the 2000s. Several small but healthy promotions put on dozens of shows each month. The events are smaller and the talent pool is diluted, but joshi puroresu companies still put on fantastic performances.

Pro Wrestling WAVE offers the best pure wrestling of any joshi promotion and is the primary promotion group for joshi’s top star, Kana. Her vicious wrestling style, avant-garde fashion sense, and outspoken nature have brought her legions of supporters, and several critics. Her story? She’s so good she’s above joshi, as she stated in a 2011 interview: “There will never be another wrestler like me. I am the only one in the world. I have no female rivals, as there are none that can fight with matching technique and heart. I can’t measure my abilities within women’s wrestling.”

Lightening the mood in WAVE is Sakura Hirota, a comedy wrestler known for her hilarious impersonations. She’s donned fake lips and noses to spoof her opponents and stuffed her top and worn school girl outfits to mock idols. Her most devastating moves are usually kisses and kanchos (goosing).

Stardom is joshi’s most publicized promotion. Like AJW, its focus is on finding the sweet spot between pop culture and old school wrestling legitimacy. “Joshi needs more media exposure. More people need to see it, not only wrestling fans, but other people as well. That’s what Stardom tries to do,” says Act Yasukawa, one of Stardom’s top wrestlers.

Act is a former actress and model, and the star of a recent documentary about her life called “Gamushara.” In the piece, Act tells how she survived illness, depression, rape, and a suicide attempt to eventually find herself in pro wrestling. “When I was younger I was bullied and unhappy. I survived and now I feel really alive, and I’m living my dream. That’s the feeling I want to give to the audience.”

These are just a few of the intriguing stories being told in modern joshi. Companies including REINA, Oz Academy, ICE Ribbon, DIANA, and LLPW run multiple events each week in the Tokyo area. If you are interested in seeing it live, you can find show listings on newsstands everywhere in “Weekly Puroresu” magazine or on puwota.com.

Top Image: Tsubasa Kuragaki’s patented “Torture Rack” hold