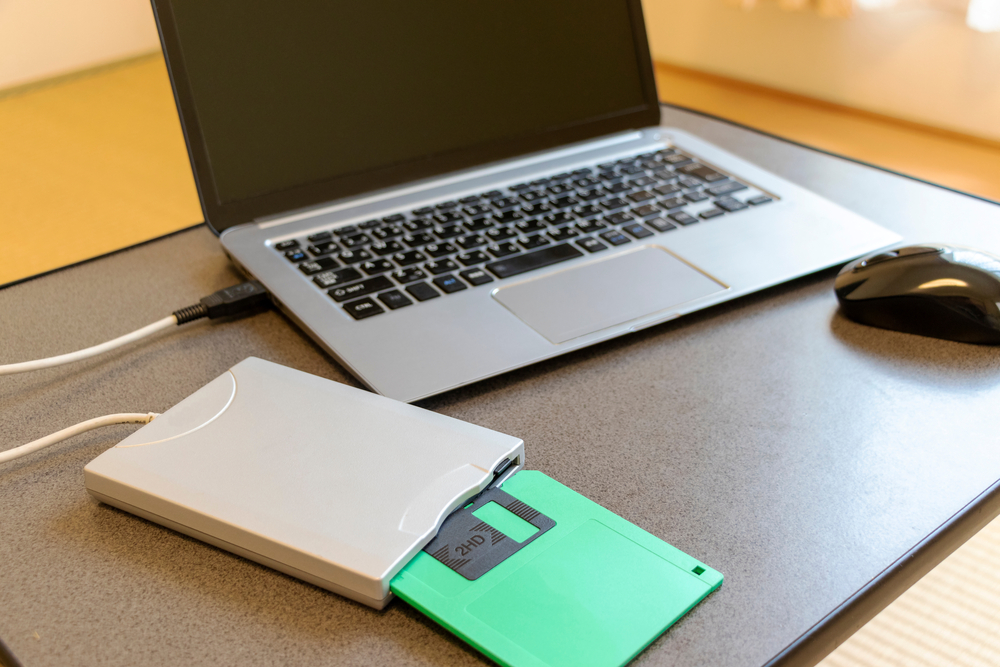

“Where does one even buy a floppy disk?” a rhetorical Taro Kono asked a room full of reporters.

Ironically, the answer is Japan. In fact, anyone who’s shuffled along the basement aisles of an Akihabara retro store, perused the shelves in a Tokyo Hard Off, or fumbled around in a Japanese office desk will tell you as much.

But I appreciate Kono’s point. I also fall right in line with the sentiment — it’s about time the government rid itself of antiquated technology.

The digital affairs minister posed the question as part of his opening gambit to “declare war” on the floppy disk. Kono, who narrowly lost out in the race for the Japanese premiership to Fumio Kishida last autumn, is arguably the nation’s highest profile political maverick; running counter to the prevailing winds with a reformist, straight-talking style that has curried little flavor with the all-powerful bureaucracy.

This came to the fore during his tenure as administrative reform minister in Yoshihide Suga’s cabinet, when Kono waged similar conquests on fax machines and hanko — which reports suggest are still used by up to 95 percent of local businesses. Japan’s paper and ink culture had been in the headlines for much of that pandemic-riddled year, with public officials and private employees trudging en masse to the office to print, stamp and fax documents they didn’t have the means to do from home.

“Why do we need to print out paper? In many cases, that’s simply because the hanko stamp is required,” Kono said in late 2020. “So, if we can put a stop to that culture, it will naturally obviate the need for printouts and faxing.”

Japan residents will be well familiar with the cognitive dissonance between its cutting-edge consumer technology exported to global acclaim versus the office spaces and government procedures that have scarcely changed since the bubble economy. Unfortunately, this resistance to change is to be expected in a deeply bureaucratic government largely presided over by old men who grew up in another era and still hold value in the perceived safety of physical media and the sanctity of the hanko-carving tradition.

Updating Japan’s digital infrastructure to be attuned to its tech-savvy image could benefit procedural efficiency, economic growth, communication channels and stakeholder experience — as has been noted in several studies (see here, here and here). Moreover, it will surely send a message to any corporation hellbent on resisting change that it’s time to wave farewell to the analog era.

Yesterday’s World

It’s little surprise the floppy disk was the next piece of arcana to fall foul of Kono’s ire. Floppy disks — used for no fewer than 1,900 government procedures, including submitting applications — hold around 1.4MB of data. That’s enough for almost one high resolution photo or a handful of thumbnails (depending on their size). Even USBs, which already feel antique due to the proliferation of SD cards, portable hard drives and cloud-based storage software, are equal to thousands of floppy disks.

It’s true, however, that the floppy disk represents a slice of Japanese history. Supposedly invented by the eccentric and prolific Yoshiro Nakamatsu — a claim disputed by the world’s first distributors, IBM — it soon become the de facto data storage device in a rapidly digitizing world. The floppy’s heyday lasted at least 30 years — I can even recall using them in the mid-1990s — before the new century ushered in an inevitable decline. Then in 2010, Sony, the last company still producing the disks, announced that manufacturing would officially cease.

The establishment and certain strands of the media have levied criticism against Kono, stating that axing floppy disks altogether overlooks their importance in Japan’s digital past.

Now, I am a sentimental sort — the type of person who buys wooden electronics, pines for the days when Snake was the only worthwhile diversion on my phone and can’t resist a good typewriter display in a shop window — so I get the nostalgic appeal. But then again, I am not operating a 120-million-strong democracy and my old-school foibles therefore affect nobody beyond my social circle. The “those were the days” argument, doesn’t really hold up in the face of technological innovation.

It’s also worth noting that floppy disks, like most pieces of technological equipment, deteriorate over time — and, frankly, weren’t that durable to begin with. So, an inflection point sits on the horizon, whether we like it or not. Necessity will have to be the mother of invention, or at the very least, change.

“Pepper” robot assistant with information screen.

Changing the Law

Legislature will pose a stumbling block in Kono’s war. The government is required by law to use floppy disks (or similar technologies, such as CDs) for certain procedures. This necessitates a legal overhaul which won’t be straightforward in the face of bureaucratic pushback.

Revised regulations are expected to be drafted within the year, upon which they’ll be presented to government agencies for compliance. Until then, we won’t officially know the floppy’s fate.

If Kono can overcome this challenge and successfully catalyze a digital shift, which his PM has already supported, then expect similarly obsolete technologies to be targeted in the future. Because if Kono’s reputation is anything to go by, plans are already being devised in the war room.

Retrophiles will, however, have a silver lining to cling to, as every time you hit “save” on a word doc or excel sheet, the floppy disk icon will be there to remind you that this is where it all began.