On this day fifty one years ago, Yukio Mishima completed the final instalment of his tetralogy of novels The Sea of Fertility. Addressed to his publisher Shinchosha, he left the papers in an envelope on a table at his western-style home. Alongside his work was a note that read, “Human life is limited but I would like to live forever.” A few hours later, he was dead.

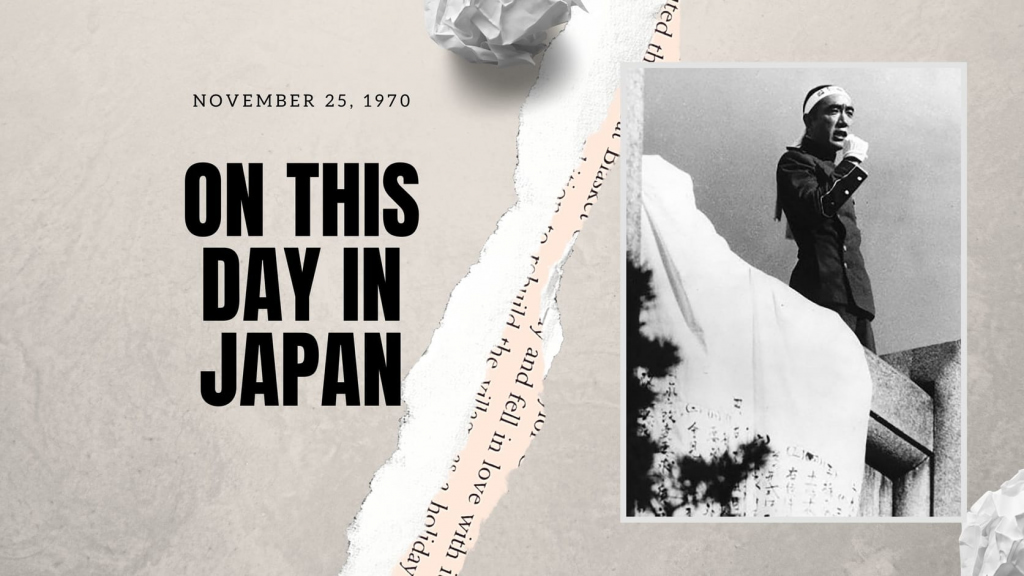

After leaving his house in the morning, the renowned author and four other members of the Tatenokai (a private militia founded by Mishima) stormed a military base in Tokyo and tied the commandant Kanetoshi Mashita to a chair. Mishima then gave a speech to a group of around 1,000 servicemen intended to inspire a coup d’état to restore the Emperor’s power. It failed and he subsequently performed seppuku (ritual suicide by disembowelment).

The event stunned the nation and sparked fears of a possible revival of militarism and right-wing nationalism in Japan. In his book Yukio Mishima, Damian Flanagan describes the incident as a “never-to-be-forgotten JFK moment,” for Japan’s postwar generation. “To the general public,” he wrote, “Mishima’s eccentric stunt could only appear as a grotesque anachronism…. an expression of ultra-nationalist sentiment that Mishima adored but which the Japanese nation would frankly rather now forget.” Five decades on and the incident, as well as Mishima’s life and work, is still being scrutinized by scholars and critics.

A Troubled Genius

Born Kimitake Hiraoka on January 14, 1925, Mishima was mostly raised by his enigmatic yet overbearing grandmother until the age of 12. She wouldn’t let him play sports with other boys or go out in the sun. At 16, he was given the nom de plume Yukio Mishima by a group of editorial board members to prevent a potential backlash from his anti-literary father. This came after he had impressed them with The Forest in Full Bloom, a short story about a deep connection he felt to his ancestors. It was published in Bungei Bunka magazine and was later released in book form in 1944.

He started working on his first full-length novel Thieves after World War II, though it was his second book: Confessions of a Mask that launched him into national fame in his early twenties. A critically acclaimed tale, widely seen as semi-autobiographical, it tells the story of a tormented adolescent named Konchan who struggles to fit into Japanese society after being kept away from boys his own age. He wears a metaphorical mask to present his false personality to the world and hide his homosexuality.

Following the success of Confessions of a Mask, Mishima continued to enhance his reputation with books such as The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Thirst for Love and David Bowie’s favorite The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea. A prolific writer who never missed a deadline, he penned around 50 plays and 34 novels, receiving three nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature. His magnum opus was the four-part epic series The Sea of Fertility that he started working on in 1964. It was completed on the day of his death, six years later.

As well as being a writer, Mishima also worked as a model and actor, appearing in films such as Afraid to Die by Yasuzo Masumura and Kinji Fukasaku’s Black Lizard, which was based on his own play. Known for his muscular upper body, he would often portray strong characters, reflecting the real image he wanted to paint of himself. In his youth, he had a hang up about his lack of height and physicality so subsequently decided to take up bodybuilding in his early thirties. Any potential wife had to obey his prenuptial demands, which included respecting his privacy and not interfering with his writing or weight training.

In 1958, Mishima married Yoko Sugiyama, daughter of famed painter Yasushi Sugiyama. Though they had two kids together, rumors about his sexuality persisted long after he died. In 1998, a book by Jiro Fukushima detailing their affair was banned by the Tokyo District Court for copyright violation. He was successfully sued by Mishima’s children for featuring 15 letters from their father in the book that they claimed should not have been used without their permission.

After the Anpo Protests against the US-Japan Treaty in 1959 and 1960, Mishima’s work began to get more political, including essays, commentaries in newspapers and most famously the short-story Patriotism about a young right-wing ultranationalist officer who committed suicide following a failed coup d’état (known as the February 26 Incident) in 1936. It was later turned into a short film that Mishima directed, produced and starred in.

Tatenokai and the Attempted Coup D’état

In 1968, Mishima established the Tatenokai (Shield Society), a small private army predominantly consisting of around 100 university students that he trained in martial arts and physical discipline. They vowed to protect their “living god” Emperor while also devoting themselves to the bushido code and traditional Japanese values (Mishima has previously criticized Emperor Hirohito for renouncing his own divinity after World War II).

Four members of the Tatenokai — Masakatsu Morita, Hiroyasu Koga, Masayoshi Koga and Masahiro Ogawa — who had displayed unswerving loyalty to Mishima and the Emperor were handpicked to assist the playwright for his final act. Ostensibly, the aim was to get inside the Ministry of Defense headquarters in Ichigaya, Tokyo and persuade the JSDF to join his militia in a coup against the government to overturn the 1947 constitution that he detested. However, Mishima’s biographer John Nathan suggested it was just a ruse and his intention all along had been the ritual suicide.

The five men had an appointment with the esteemed General Mashita who they took hostage before barricading themselves in. Mishima then went out to the balcony to address the soldiers (and some press who had gathered), during which time he decried the constitution that was effectively “denying their existence,” and urged them to join his uprising. The irritated crowd booed and heckled, drowning out much of what he said. A planned 30-minute speech finished around seven minutes in with the words “Long live the Emperor!” three times. He went inside, apologized to the commandant, explained why he had done it and disemboweled himself with his sword. It was the first act of seppuku since World War II.

The “kaishakunin” (assigned to behead an individual who has performed seppuku) was Mishima’s faithful follower (and rumored lover) Morita. Despite three attempts, though, he was unable to complete the task, striking him on the shoulder each time, so Koga took over. Morita then stabbed himself in the abdomen before being decapitated by Koga. Mishima, who had meticulously planned the event over a year in advance, made sure the three surviving members of the coup were left with enough money for their legal defense.

Mishima’s Legacy

Reaction to the Mishima Incident was unsurprisingly mixed. Fans of the writer saw his suicide as a noble and gallant sacrifice needed to revive a nation that had sold its soul to the west. For many others, it was simply a worthless and potentially dangerous act by a narcissistic man who had long been obsessed with a masochistic desire to take his own life. Those in power, meanwhile, were keen to depoliticize his actions and paint him as a deranged radical. “I can only think he went out of his mind,” said then-prime minister Eisaku Sato. “If he had given thought to revising the constitution, there must have been some other method. It is difficult to understand why he resorted to such an act of violence.”

In the 50 years since the attempted coup, Mishima’s posthumous reputation has grown. His name is no longer taboo here. Neither are his views, particularly about the need for constitutional changes that many modern-day conservative politicians (though few if any would associate themselves with him for fear of damaging their reputations). The significance of his work, previously downplayed in Japan, has been celebrated widely in recent decades. Yet, despite being revered as one of the most important and influential writers Japan has ever produced, it is still the dramatic event that occurred on this day in 1970 for which he is most remembered.

“On This Day in Japan” is a new Tokyo Weekender series that retell significant historical events, accidents and incidents that have had a major impact on Japanese society, politics and culture.