On the day we are scheduled to meet, I arrive early, impatient and restless. It has been nearly a decade since I first envisioned this moment – sitting face-to-face with the second (out of only two) Japanese woman to fly in space and the only woman from Japan who achieved this while raising a child. As a college student concerned about my future, I first spotted one of Yamazaki’s books at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) souvenir store in Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture. The book had Yamazaki on the cover, in her signature orange uniform, smiling with the type of confidence an uncertain kid like myself at the time looked up to for inspiration and assurance. The cover read, “Things will work out,” and the strong image Yamazaki was portraying, as natural as she looked, gave me some reassurance that, indeed, it would all work out.

Fast forward to 2020, my fate crosses paths with Yamazaki once again: although this time instead of seeking professional confidence, I am reaching out to learn what her experience in space — the universe’s most isolated place — can teach us about how to handle the new reality we are living amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Japan had just emerged from nearly two months of self-isolation under the national state of emergency imposed to battle the virus. The world had it worse. Thousands were losing their lives to the virus daily; millions were locked in their homes battling loneliness, isolation and uncertainty. The pandemic had hit the globe hard and the unfortunate reality was that we were utterly unprepared to face it. We were also equally not prepared for the second, much more profoundly rooted pandemic of rampant global racism that people across the world were simultaneously starting a revolution against, for yet another time in history. The world felt divided on so many fronts and the confusion it had brought with it was profoundly alarming.

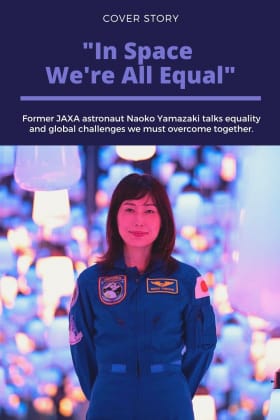

Naoko Yamazaki at teamLab Borderless’ “Forest of Resonating Lamps” room, Odaiba, Japan, June 2020

“Sometimes we just have to accept what’s happening,” Yamazaki tells me as we sit down to talk in a soft but convincing voice. “But there is always something we can do in every situation.” I take out my note pad, ready to hear it all as I find myself imagining what it’s like being out there in a completely isolated place surrounded by uncertainty — and yet, filled with so many possibilities.

Initiating the change

Born in Matsudo, Chiba Prefecture in 1970, Yamazaki grew up partially in Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island, where she discovered her passion for the stars at an early age. “The sky was so clear and beautiful,” she recalls. But it wasn’t until she witnessed the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986 on TV — she was 15 at the time — that she considered a career in space. “I remember thinking that this wasn’t science fiction. The people who perished in the disaster were real.” She was quick to focus her thoughts on those who had worked tirelessly to support the Challenger crew from the ground. “That’s when I first thought that I wanted to become a part of future space programs.”

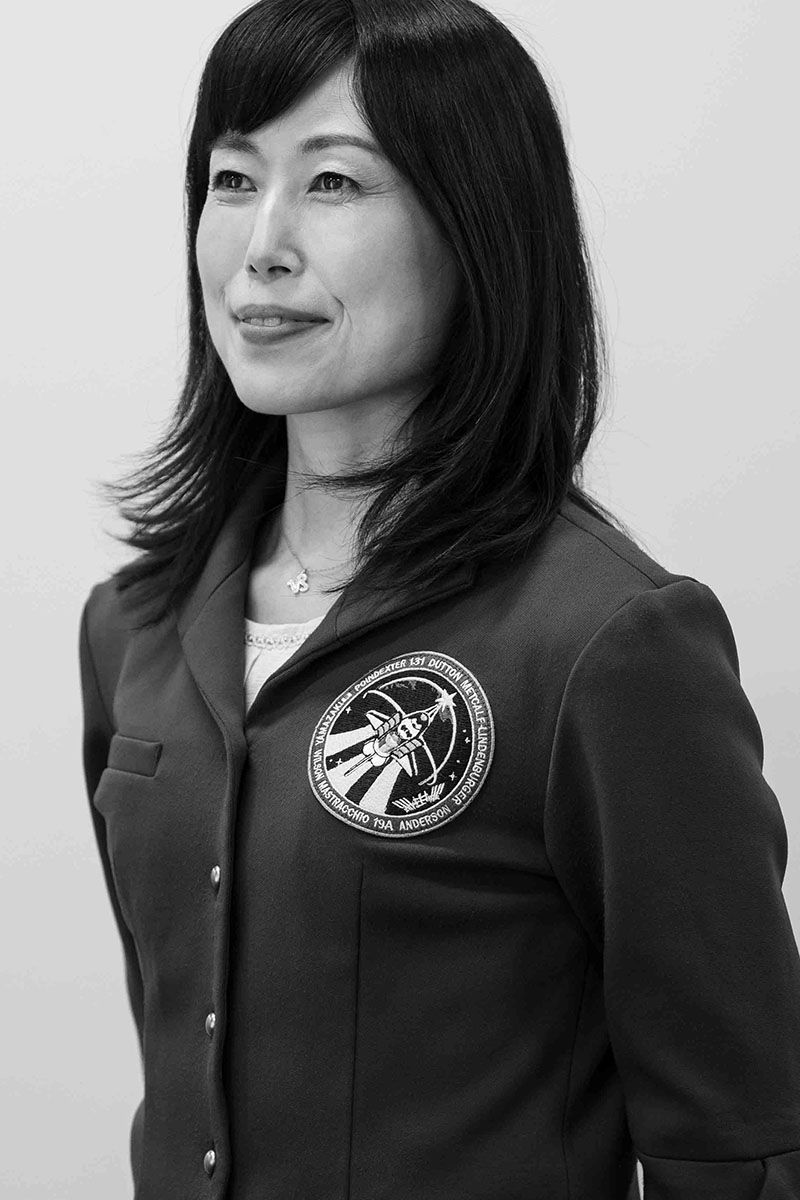

Naoko Yamazaki talks to Tokyo Weekender in an interview in late June in Tokyo

After her graduation from Tokyo University with a master’s degree in Aerospace Engineering in 1996, Yamazaki joined the National Space Development Agency of Japan (currently known as JAXA) as a member of the development team for the system integration of a module developed for the International Space Station (ISS). Following one failed attempt (she was eliminated in the first screening), in 1999 Yamazaki became one of only three members, out of 864 applicants, to pass the national astronaut candidate selection test. The final test, she recalls in her second book, Naoko Uchuhikoshi ni Naru (Naoko Becomes an Astronaut), was to be locked for a week in a simulator spacecraft with seven other candidates — all men. They had no privacy. And no windows. This, she recalls, was her very first encounter with complete isolation from the rest of the world.

Naoko Yamazaki

She passed the test, however, becoming an officially selected astronaut candidate in February 1999, along with fellow Japanese astronauts Satoshi Furukawa and Akihiko Hoshide. From then on it was a constant battle of preparation: she attended the ISS Astronaut Basic Training program, undergoing nearly two years of extreme training – including a survival camp in minus-20 degrees Celsius in Russia, where she and other candidates had to cut trees to start a fire; and another in the United States where she had to escape out of a simulated crashed helicopter sinking in water. The harshness of these training sessions, however, is what made her stronger, she recalls. “Thanks to those lessons in failure, we could get ready for almost all emergencies in space.”

“We are facing common global challenges that concern us all: global warming and Covid-19, to name just two.”

In 2001, Yamazaki was, at last, certified as an astronaut. She embarked on a steady journey toward space while participating in numerous missions and further training. In 2004, she joined NASA’s Astronaut Candidate Training, and in 2008, Yamazaki received the good news about her first mission in space via a phone call from NASA.

“At first, I thought I had done something wrong — it wasn’t common to get a phone call from the head of NASA’s Astronaut Office,” she says, laughing. The call was followed up by a short congratulatory message informing her that she was going to space for the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-131) mission set to launch in April 2010. She would later be appointed a mission specialist and her role was to deliver a multi-purpose logistics module filled with science racks that were transferred to laboratories on the International Space Station. “It was extraordinary. I had been waiting for this moment for years.”

It takes two – and more – to tandem

On April 5, 2010, Yamazaki reached space in eight minutes and 30 seconds. Along with six other crew members and seven technicians, Space Shuttle Discovery was on its longest flight in history and Yamazaki was there, making the headlines. It was the first time that four women — a vast minority in the aviation industry — stayed in space simultaneously and the first time a Japanese mother had achieved the mission. “It was a rollercoaster of emotions. As I approached the window, I saw the Earth above my head. It was shining and reflecting the sunrise and it looked alive. It was simply breathtaking.”

Amid this unforgettable experience, however, Yamazaki’s mind was with her family back home. Although her then seven-year-old daughter Yuki had gotten used to having a busy mother (she was only 11 months old when Yamazaki first left for training in Russia), Yamazaki’s former husband Taichi Yamazaki, a flight controller at the time, had become the primary carer of their child while also caring for his aging parents. “I think it was really hard for him at the time,” Yamazaki says, admitting that she frequently felt guilty for being unable to be with her family.

Naoko Yamazaki at teamLab Borderless’ “Forest of Resonating Lamps” room, June 2020

“I couldn’t make it on my own – none of it,” she says. While in space, Yamazaki remembered how long the road had been to make her dream come true. Her daughter Yuki was still a toddler when they moved to Houston for Yamazaki’s training. Alone there, while Taichi was sorting out his work back in Japan, the two were sent on another training mission — this one for Yuki to understand her mother’s work and for Yamazaki to get used to being a working mother in space. “I would often take my family to my training site to see what I do every day,” Yamazaki recalls. Whether because of this or not, Yuki grew up understanding her mother’s work. “She sometimes cried, wanting me to stay home, but she has never told me not to go to space.” Yuki now wishes to work in science too, Yamazaki says with a smile.

“The Earth is our spacecraft and we are all its members, each carrying their own unique role and responsibility.”

After her return to Earth, Yamazaki was here to settle: she took some time off to give birth to her second daughter in 2011 before she began working as an educator, an advisor at Japan’s Space Policy Committee and a developer of the future of Japanese space aviation. In 2018, she co-founded Space Port Japan, an association whose final mission is to send manned spacecraft from Japan to explore space further. “Our goal is to send Japanese manned spacecraft – in addition to our already set satellites — to space by 2027,” Yamazaki says, adding that she and her team are now preparing the country’s first legislation on sending human beings in spacecraft from Japan. Her life post-retirement is still living the space dream, but at a slower tempo, one star at a time.

Common goals, common grounds

As our interview comes to an end, I ask Yamazaki the final question: How can we use her experience — of a person who has faced extreme isolation, separation, lack of privacy, pressure from work and parenting, gender misrepresentation, and, as the only Asian woman in her Discovery crew, being an ethnic minority (in most cases, all at once) — in coping with the problems we are currently facing in our lives. She shakes her head, however, looking almost apologetic in preparing me for an unexpected answer.

Naoko Yamazaki at teamLab Borderless’ “Weightless Forest of Resonating Life” room, June 2020

“Astronauts are all rivals — everyone wants to go to space earlier. But we know that we must support each other, not only for the global good but also for purely practical reasons: If we support each other, we can succeed in many missions, which means that our time to go to space will come sooner.” Space teaches you equality, acceptance, resilience and patience, she tells me — and it also teaches you to be grateful.

“I couldn’t make it on my own – none of it”

“In space, we all have the same mission and goal to survive and to succeed. Understanding each other and building unity is essential. Our life in space is supported by many people on the ground, which is similar to life in quarantine. Acknowledging those people’s work and appreciating their contributions is important. Enjoying each change every day, no matter how insignificant, can help you in your battles.”

We can apply this to the world we live in now, Yamazaki suggests. “From space, we can see traces of global warming. It is evident. We are facing common global challenges that concern us all: global warming and Covid-19, to name just two.” Racism, class and societal division, discrimination and “othering” too, I add. She nods. “If we unite our strengths to exchange our information, we can defeat those challenges.”

“The world is bigger than you imagine, you know,” she says, smiling as we head out. Indeed, I think. There aren’t national borders seen from up there, I imagine. Just as there aren’t borders to our weaknesses — or possibilities — when we face a common challenge. Long after my encounter with her ends, Yamazaki’s words stay with me: “The Earth is our spacecraft and we are all its members, each carrying their own unique role and responsibility.”

Photography by Allan Abani. Makeup and hair by Phoebe Lin. Interview venue: teamLab Borderless, Odaiba, Tokyo.

For updates on her career and life, follow Naoko Yamazaki on Twitter at @Astro_Naoko

Updated On July 31, 2020