Seventy-nine years ago this week, the world changed forever. The United States unleashed the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 — the first time that nuclear warfare had ever been used. Just three days later, on August 9, Nagasaki suffered the same fate. Japan surrendered on August 15, with the formal agreement to bring the war to an end signed on September 2.

The advent of nuclear warfare, however, didn’t just end the war; it ushered humanity into the Cold War. With nine nations now armed with nuclear arsenals, the threat of mass destruction looms constantly over our collective consciousness like a perpetual Cold War. For many, however, the true scale of an atomic bomb’s devastation remains an unimaginable horror, confined to the annals of history.

The Collective Denial of Atomic Horror

The depth of that lack of knowledge, as well as the sheer refusal to confront the reality of the atomic bomb, has come to light lately. Just yesterday, on August 8, 2024, the U.S. and other Western allies announced they would be boycotting the Nagasaki Peace Ceremony due to Japan not inviting Israel to the event.

Notably, Israel is currently on trial for genocide in the International Court of Justice. The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court has requested arrest warrants for Israel’s leaders for crimes against humanity. The United States, the very nation responsible for the atomic bomb, is refusing to attend a peace ceremony on the grounds of reasonable diplomatic exclusion.

Additionally, Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer premiered in 2023, and in 2024 in Japan. This blockbuster, chronicling the story of scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer and the creation of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, garnered seven Academy Awards and five Golden Globes.

Conspicuously absent from the story was the impact the two bombs had on the two Japanese cities. When questioned about his choice to omit images of Hiroshima, Nagasaki and their victims, Nolan claimed that “less can be more,” implying that subtext and audience imagination are more powerful than explicit visuals. This rationale rings hollow in a world where few films dare to show the true horrors of the bombings or the faces of the survivors.

In a pivotal scene, Oppenheimer himself turns away from images of Hiroshima’s ground zero, shown to him and his Manhattan Project colleagues. As I watched, I couldn’t help but wonder if this decision subtly encouraged the audience to look away as well.

Barefoot Gen Vol. 2 by Keiji Nakazawa

An Introduction to Barefoot Gen

Keiji Nakazawa couldn’t look away, no matter how much he wanted to. When he was just 6 years old, an atomic bomb was dropped on his hometown of Hiroshima. He decided to start writing about the reality of what he experienced when his mother died. As he saw the tiny bone particles at the crematorium, Nakazawa thought about his mother, who raised her three remaining children despite her life being ruined by the atomic bomb.

“Once her body was cremated, my heart became filled with fury. There were no bones among the ashes. All I could find were tiny bits of bone, and I wasn’t able to tell whether they came from her head or her feet. I was outraged. The atomic bombing even deprived me of my mother’s bones,” he told The Chugoku Shimbun’s Rie Nii during a 2012 interview.

Nakazawa went on to author the autobiographical manga Barefoot Gen, with its first volume published in 1973. The series ran for over a decade and was adapted into three live-action movies and two anime films. The most notable adaptation, also titled Barefoot Gen, premiered on July 21, 1983, 40 years before Oppenheimer premiered in the States.

The Unflinching Brutality of Barefoot Gen

This film, directed by Mori Masaki and written by Nakazawa, follows Gen Nakaoka and his family in Hiroshima in the final months of World War II. Gen, a 6-year-old boy, lives in a modest, weathered house with his younger brother, older sister, mother and father.

He and his younger brother, Shinji, are typical boys — brimming with energy and mischief. They often fantasize about feasting on rice balls and sweet red bean paste. Their young minds escape into dreams. They are nearly inseparable, sharing everything from their scant meals to the thin, fraying futons they sleep on.

Their mother, Kimie, is gentle yet weary. She’s also pregnant with another child. The family eats simple meals of watery rice gruel, eked out with a few pickled vegetables. The Nakaokas are a poor but tight-knit family.

All of this changes on the morning of August 6, 1945. The day dawns hot and clear, the oppressive heat of summer pressing down on the city. Gen and a friend arrive at school as usual. In an instant, the world is bathed in an unnatural, blinding white light, as if the sun itself has descended upon them. The air crackles with an eerie silence, the calm before the storm. Then, the bomb drops.

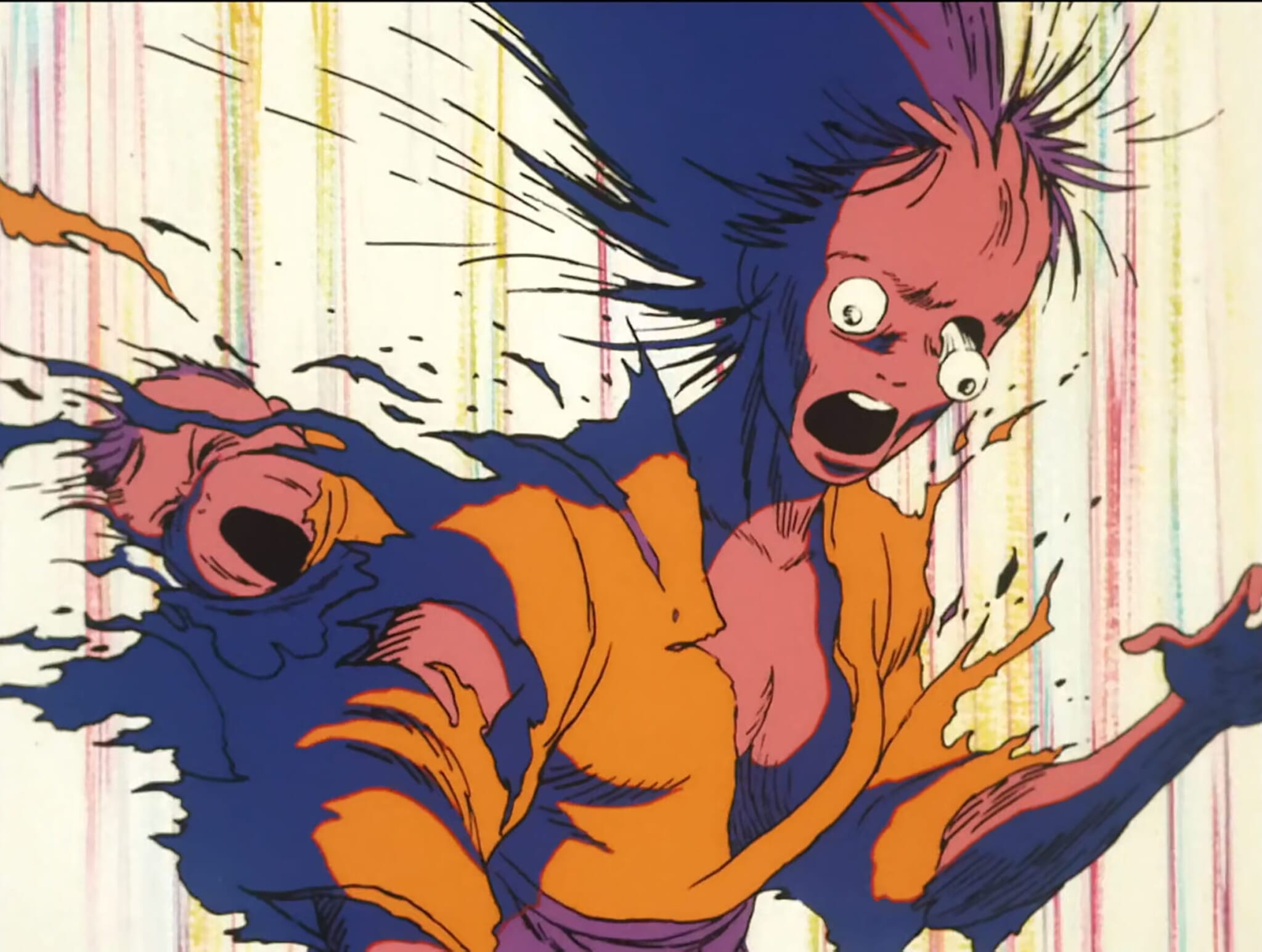

The explosion is a cataclysm. The film captures the moment in agonizing detail: the searing heat wave that radiates outwards, vaporizing everything in its path. People are not merely killed — they are erased, reduced to shadows burnt into the walls, their forms etched in a final moment of existence.

A young girl is incinerated, her eyes bulging and oozing from their sockets as they liquefy, her skin bubbling, blistering and peeling away in agonizing layers until all that remains is a husk of ash. A postman, an elderly man, a mother clutching her newborn and a dog all suffer the same fate.

Gen is hurled to the ground. When he opens his eyes, he is confronted by a vision of hell. The sky, once a brilliant blue, is now a churning mass of black and red, as if the heavens themselves are weeping blood. His friend lies lifeless in the carnage.

Staggering to his feet, Gen begins the search for his family. The air is thick with ash and the acrid stench of burning flesh. Returning home, Gen claws through the debris, his hands raw and bleeding. He finds Kimie trapped under the wreckage of their home and pulls her out, but his brother, sister and father remain trapped inside their burning house.

Gen and his mother are forced to leave their family behind. The fire consumes everything in its path, including the fragile bodies of his father and brother. His father’s last words are a plea to Gen to survive. To protect his mother and the unborn child she carries. It is a charge that will weigh heavily on Gen’s small shoulders.

Some might call this too graphic, but it mirrors the very horrors Nakazawa lived through firsthand.

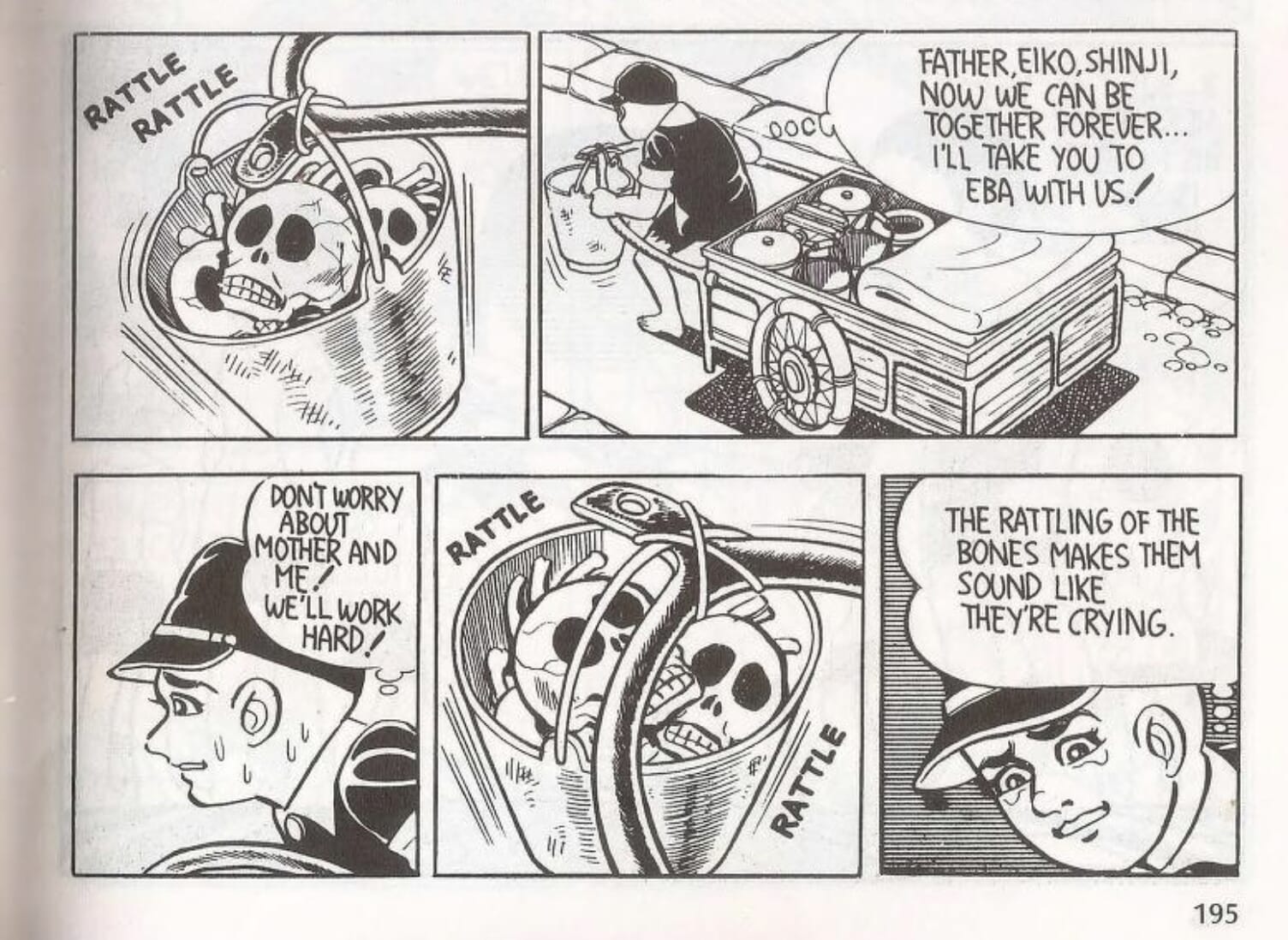

“We found a child’s skull at the entrance to the house, like my mother had described. I can’t forget that moment I held Susumu’s skull in my hand. Even in the scorching heat of August, I felt an overwhelming chill, as if a great pile of ice was poured down my back. My younger brother was still conscious when he burned to death,” he told The Chugoku Shimbun. “My mother told me she could hear my brother’s screams from the blaze. His screams continued to echo in her ears. Throughout her life, she was haunted by the cries of Susumu and my father.”

“In the room next to the entrance, we found my father’s skull. Digging in another small room, we found my sister’s skull, too. The bucket became filled with their bones,” he continued.

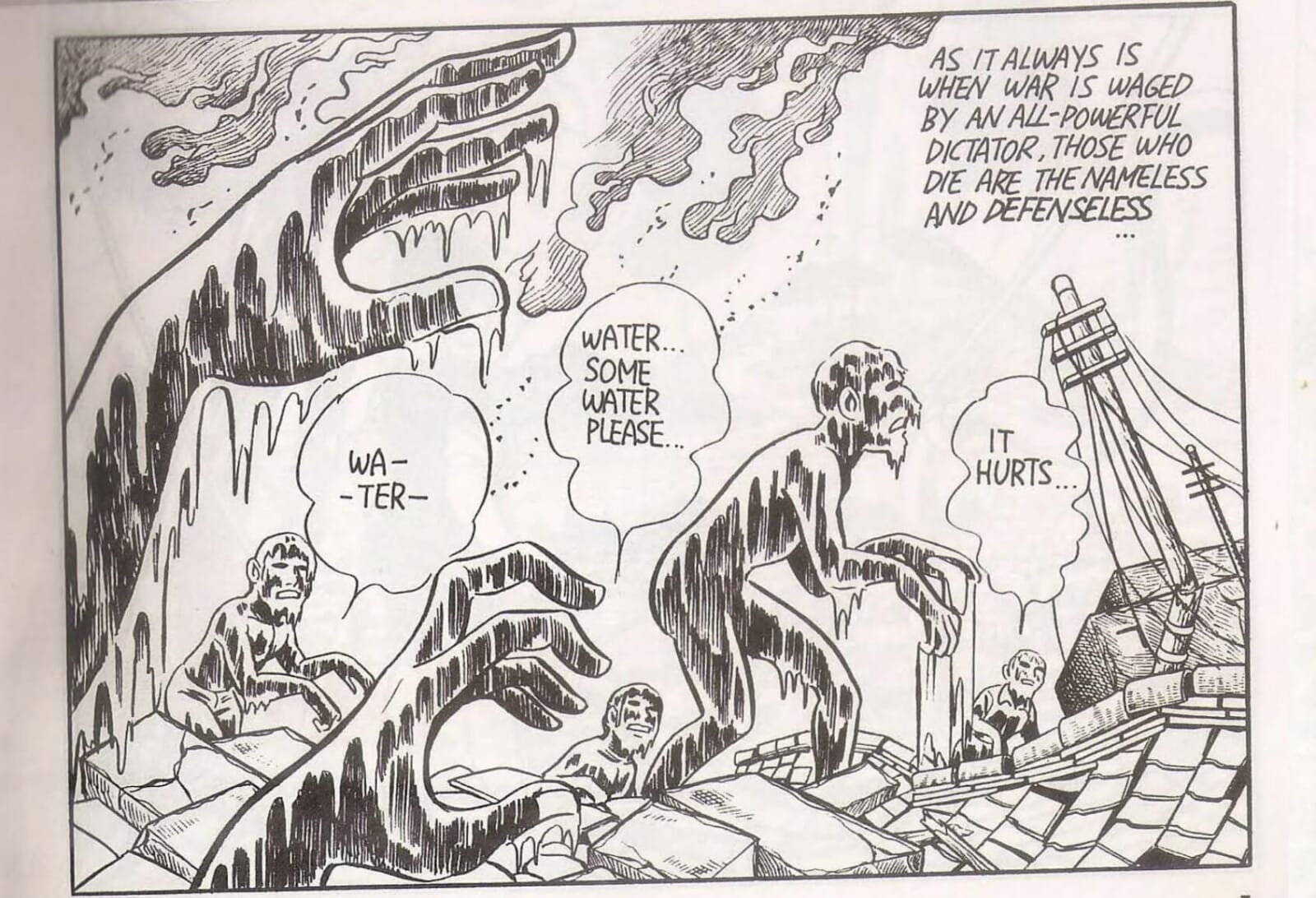

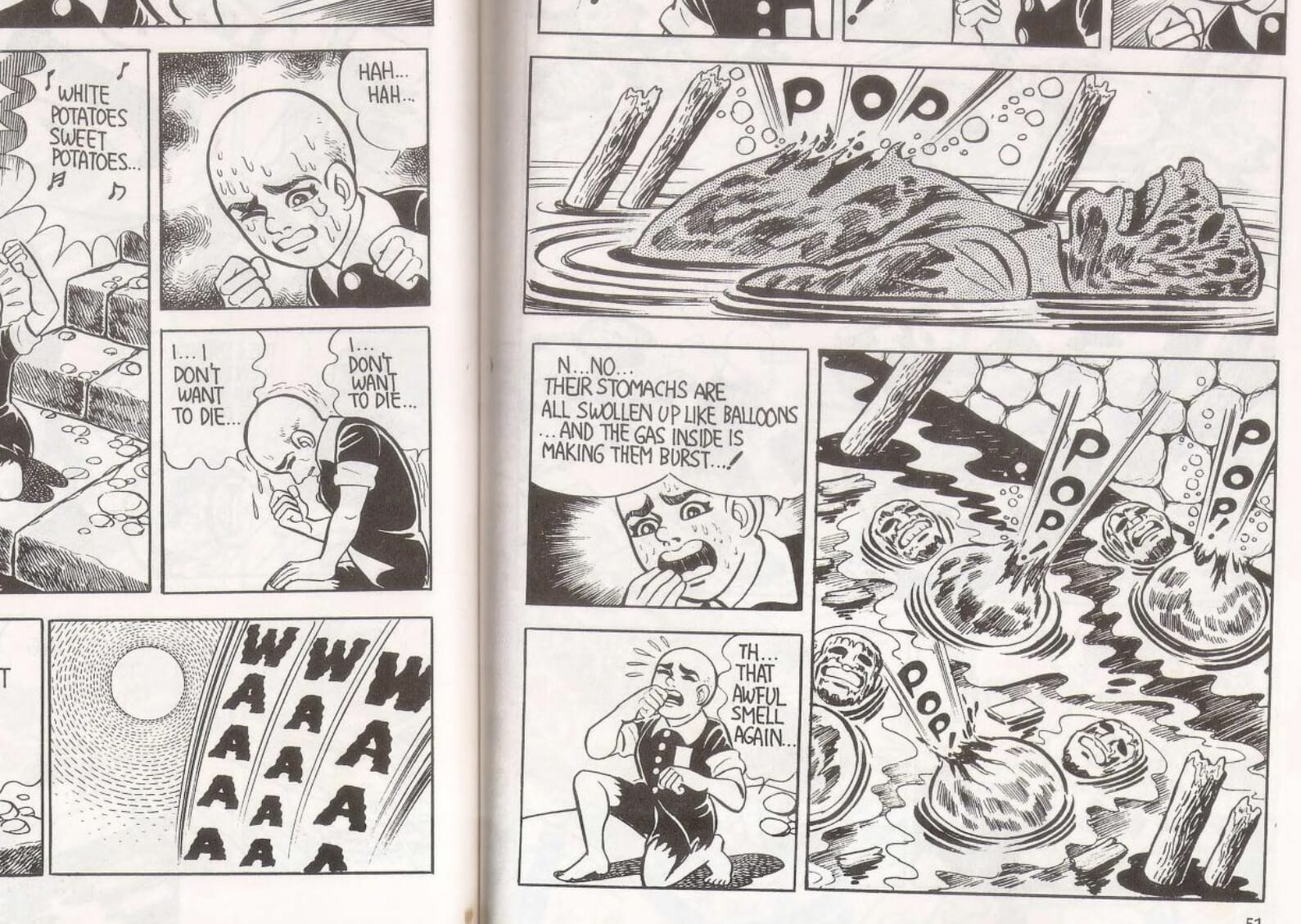

In the aftermath of the bombing, Hiroshima becomes a city of ghosts. The survivors are living skeletons. Their skin sloughing off in grotesque sheets. Their eyes hollow and vacant. The film does not shy away from the gruesome reality of radiation sickness: the hair loss, the open sores that refuse to heal and the maggots that infest them, the slow, agonizing deaths that follow. Bodies litter the streets, some charred beyond recognition, others bloated and disfigured from radiation poisoning.

One of the most gut-wrenching scenes is the sight of infants still suckling at the breasts of their dead mothers, too young to comprehend that the source of their nourishment is no longer alive. The babies cry out. Their tiny hands grasping at cold, unresponsive flesh, their hungry mouths stained with blood.

This, too, parallels the reality that Nakazawa went through.

“Around me were a lot of people whose skin was drooping from their bodies. The skin was peeled from their shoulders to the backs of their hands, where it dangled from their fingernails. The skin from their backs hung from their buttocks like some kind of fabric wrapped around them. As they dragged the skin of their legs behind them, they were unable to lift their feet. A crowd of these people was approaching me,” said Nakazawa to The Chugoku Shimbun.

Amid the ruins, Kimie gives birth to a baby girl, Tomoko: a fragile new life in a world torn apart. Gen, driven by a fierce love for his sister, takes on the role of her protector. He works tirelessly to provide for her. Finally securing a job, scraping together enough to buy her milk. But the cruel reality of their situation is unforgiving — Tomoko, weakened by malnutrition, dies before he can save her.

Yet, in the midst of this relentless misery, the film pulses with a glimmer of hope. Gen and his mother endure, and, against all odds, the possibility of a future emerges. A young boy enters their lives, bearing an uncanny resemblance to his dead brother Shinji, hinting that even in the most desolate circumstances, the Nakaoka family might find a way to rebuild — just like the resilient grass that begins to push through the scorched earth as the film draws to a close.

Barefoot Gen Vol. 2 by Keiji Nakazawa

The Necessity of Remembering

Barefoot Gen is revolting. It’s graphic. And it’s almost unbearable to watch. But that’s exactly the point. The reality of an atomic bomb isn’t something that can be softened for delicate sensibilities. Instead of indulging in saccharine films that gloss over history’s darkest moments, maybe it’s time that we confront the brutal realities we’ve long chosen to ignore. Films like Barefoot Gen wrench our eyes open to the brutal truths of the past, forcing us to reckon with the nightmarish devastation wrought by the atomic bombs.

America must confront its monstrous actions and acknowledge the unimaginable suffering it inflicted. Japan, too, must confront the full extent of the suffering endured and its own wartime guilt. Sanitizing and censoring these painful memories does nothing but spit on the graves of the victims. To learn anything, to pay proper respect, we must face these horrors head-on, with the full weight of their brutality bearing down on us. Only then can we begin to understand the true cost of these atrocities and honor those who suffered.

Keiji Nakzawa passed away on December 19, 2012. He left behind these words:

“I can still speak, so I will definitely keep conveying the idea that Gen is angry. I believe that the Japanese people still need to examine their responsibility for the war and the issue of the atomic bombings.

“I will thoroughly bring to account those responsible for the war and the atomic bombing, whether they are the Japanese government authorities or the U.S. government authorities. Through manga, I will fight them to the last stand.”

For those who suffered through nuclear warfare, the trauma isn’t a relic of the past but a daily reality. The effects of radiation continue to torment not only humans but the environment as well. Scientists remain baffled by the conundrum of managing highly radioactive nuclear waste, whether from power plants or former test sites that are too contaminated to inhabit.

As global tensions escalate and the specter of nuclear war looms ever larger, it is imperative to reckon with the ongoing legacies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. To foster a more balanced understanding of nuclear weapons, we must stop turning away from uncomfortable realities and heed the voices and stories of those who lived through the carnage. Their firsthand accounts are not just historical footnotes but urgent, living testimonies that demand our attention and action.

Barefoot Gen Vol. 2 by Keiji Nakazawa

Related Posts

- U.S. and Other Western Ambassadors To Skip Nagasaki Peace Ceremony Due to Israel Snub

- Tsutomu Yamaguchi: The Man Who Survived Both Atomic Bombs

- Uncover Nagasaki’s Hidden History

Updated On August 9, 2024