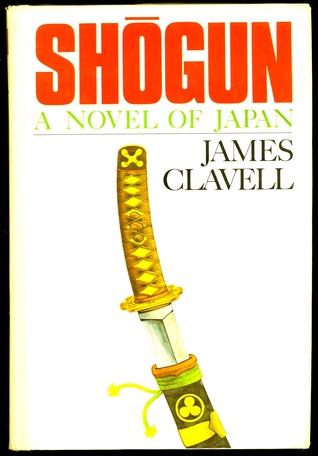

Earlier in August, John Landgraf, CEO of American television network FX, felt the need to let the world know that the upcoming new TV adaptation of James Clavell’s 1975 novel Shogun will not “fetishize” Japanese culture. He also pointed out that among all available gazes the male and Western varieties will be kept to a minimum.

Mr. Landgraf’s anticipatory defense against crimes not yet committed was not entirely unmotivated. Journalists had already been musing and inquiring about how offensive exactly FX was planning to make the new Shogun, so they could plan their level of outrage well in advance (the project has yet to move past the casting stage).

The original book is based on Ieyasu Tokugawa’s historical rise from feudal lord to the head of the Tokugawa shogunate in the 17th century, as witnessed by the first British sailor ever to arrive in Japan.

Allowing more than one viewpoint in a grand tale with more than one character of more than one gender and more than one cultural background is all well and good. It’s a shame about the refusal to fetishize culture, though. It is also highly doubtful that it can be done.

All Art Is Fetishization

Fetishization, the obsessive, often idealized commitment to very particular aspects of a subject, is at the heart of all arts and entertainment. American cinema has always fetishized its country’s culture of cowboys, gangsters, war heroes, politicians and astronauts. Japan does the same on its own shores, churning out historical dramas without much regard for historical accuracy. As science fiction fetishizes outer space and machinery, so does period drama with the costumes and customs of the past.

One might argue that criticism is due when the fetishization takes place outside of the fetishizer’s own culture. That can be correct in some cases, but it’s hardly a universal truth. Nobody cried cultural appropriation when in the 1960s and ’70s the finest Westerns were coming out of Italy.

A few weeks ago I sat down at one of the many Oktoberfests here in Tokyo, where the Japanese routinely fetishize German culture. Compared to those in my home country, they didn’t get it quite right. You might even say they were resorting to stereotypes. Did I stamp my foot and start a petition? No, I grabbed a beer and enjoyed it for what it was. No German culture was harmed that night. Just like no Japanese culture was harmed that time Kate Perry dared to wear a kimono, or when Avril Lavigne had the nerve to shoot a music video in Japan. Both were matters of grave concern a few years back, mostly to non-Japanese outrage chasers. Japanese culture is strong, however. It’s not a delicate flower that will be crushed by a little foreign fetishization.

Sensible Standards

Like any Westerner coming of age in the 1980s, I was glued to the TV when the first Shogun adaptation starring Richard Chamberlain was on. I am sentimental about the experience, not necessarily about the product. I haven’t revisited it since, and if I did, I would fully expect to find something that does not meet my current standards for political correctness or “wokeness.” My standards might be considered slightly below average in our age of hyper-sensitivity, yet I do have some. Still, it wouldn’t cross my mind to approach the new adaptation with a catalogue of demands and a list of acceptable pronouns. We are not entitled to custom-made TV entertainment, carefully tailored around our own personal triggers, tastes and sensibilities.

I will approach the new Shogun only with hope. I hope we will get a damn fine adventure yarn, preferably one featuring daring men and beautiful ladies, but also strong women and handsome gents. Television is a visual medium, after all. And if we don’t like what we see, we can still turn it off.

Photograph: Shutterstock