“Our country, as a special mark of favor from the heavenly gods, was begotten by them, and there is thus so immense a difference between Japan and all the other countries of the world as to defy comparison. Ours is a splendid and blessed country, the Land of the Gods beyond any doubt.”

The 19th-century theologian Hirata Atsutane may have been describing the splendor of pre-industrial Japan, but you could, at only a slight stretch, supplant his impassioned panegyric onto Japan’s jazz scene. Not necessarily because Japan has produced the greatest jazz musicians — though the likes of Sadao Watanabe and Toshiko Akiyoshi may have something to say about that — but because of the reverence with which the country has treated the genre and its pioneering virtuosos.

No matter how expertly you played the drums or how transcendent your saxophone melodies were, if you were Black in the 1960s, America was not an auspicious place to be. So, you can imagine Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers’ amazement when they arrived on the tarmac of Tokyo’s Haneda Airport in 1961, their music blaring from the airport’s speaker system, while fans clambered over one another to present them with gifts and bouquets of flowers. Miles Davis, Ray Brown and Charles Mingus were equally enamored when they performed at sold-out venues across the country, while Duke Ellington made his love of Japan clear after hearing the rapturous applause at Shinjuku’s Kosei Nenkin Kaikan during a 12-day tour in 1964. Similar stories follow the legends of John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, Bud Powell and Elvin Jones.

Because of the segregation and unequal treatment they were subjected to at home, these musicians sought recognition for their talents abroad and felt duty-bound to spread the spirit of the American civil rights movement. Perhaps surprisingly, they found common ground in Japan, a nation that had freely adopted jazz and was in the midst of its own sociocultural revolution.

Jazz Kissa: An Ode to Times Past

Jazz kissa, cafés where people would go to drink coffee or alcohol and smoke cigarettes while listening to imported records, arose to meet the growing demand for modern jazz. By the 1970s, there were more than 250 jazz kissa in Tokyo alone. Even Haruki Murakami owned one called Peter Cat in Kokobunji before an epiphany at a baseball game in 1978 inspired him to become an author.

But as musical tastes changed and owning a jazz kissa lost its fashionable luster, the culture embarked on a steady decline. Tokyo has lost around 100 of these establishments over the past half-century. And with many proprietors still in business since the halcyon days of the 1970s — and no successors waiting in the wings — more will soon close their doors forever.

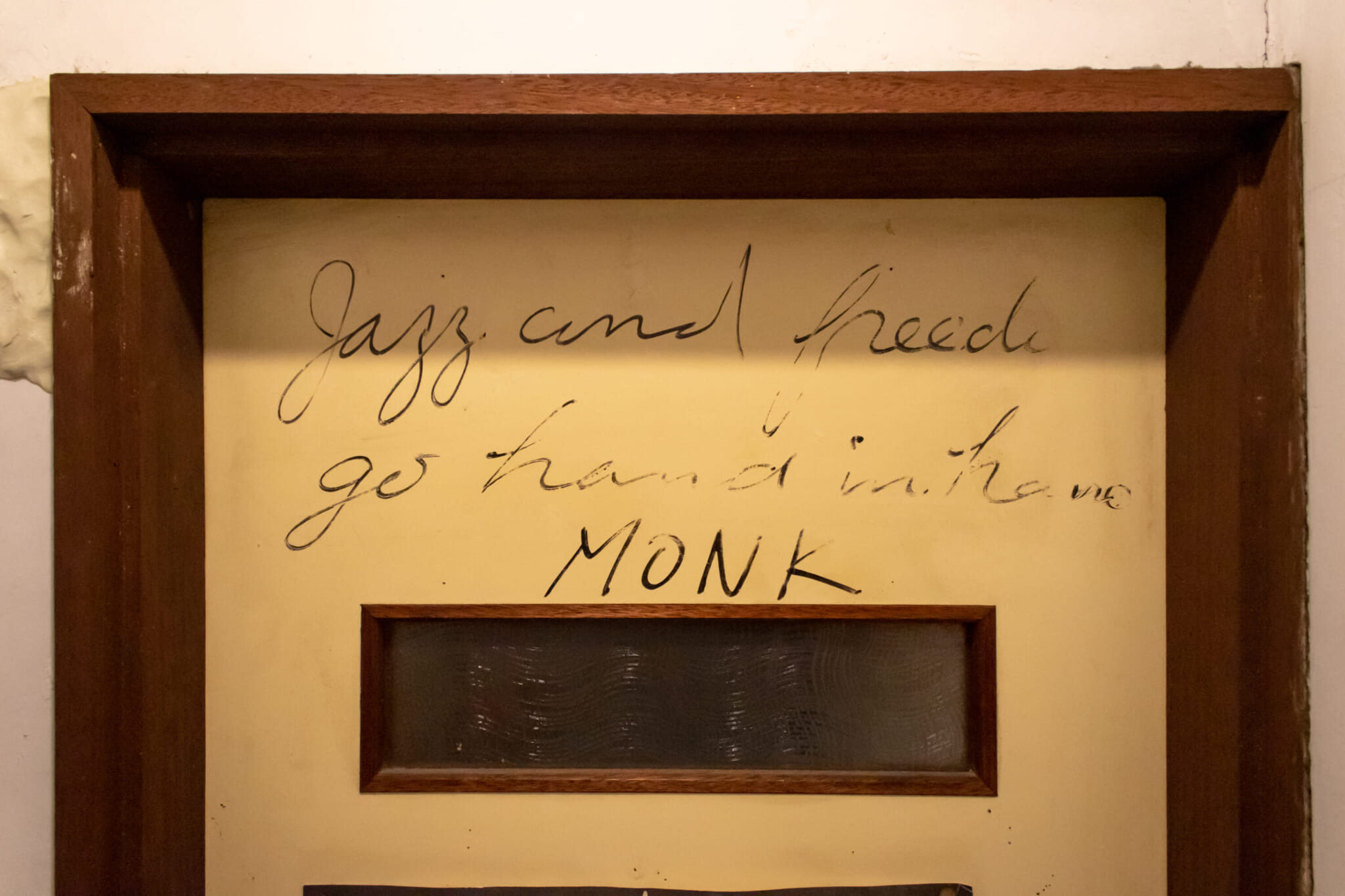

To visit a kissa is to experience a side of jazz culture that is unique to Japan. These atmospheric enclaves, often jaundiced with age and battered by decades of tobacco smoke, hold rich archives of jazz records that reflect the owners’ personal tastes. Low-wattage bulbs illuminate the accompanying memorabilia: signed photos, album covers and old magazines for customers to peruse. Patrons tend to be few and far between, and those that appear are likely regulars: salarymen who while away their evenings in solitude, joined only by the sounds of Monk and Duke, or retirees reflecting on the years when student activism and countercultural jazz blossomed into a spiritual relationship.

Jazz Room Stick, Tokyo (now closed) | ©Philip Arneill

Jazz for Everyone

I recently spoke to Philip Arneill, a fellow Belfast-born Tokyoite and an acclaimed photographer who’s set to release Tokyo Jazz Joints, a photobook on the vanishing world of Japanese jazz kissa. Arneill described these haunts as pseudo-religious spaces. It felt like the perfect analogy. The owner, or “Master,” presides over the music with ceremonial rigor and curates albums with the devotion of a zealot. The vinyl records, though weathered by use and time, are the founding texts of the belief system. They are played on turntables and analog speaker systems that stand sentry in alcoves like musical shrines. The artists themselves are gods in the jazz pantheon, using music as their vehicle to reach the promised land.

Though common themes persist in jazz kissa culture, each establishment has its own defining characteristics. You’ll find kissa that play music in a wide variety of styles, others will focus on hard bop or experimental jazz. Some are in renovated basements, such as Eagle in Yotsuya or Dug in Shinjuku. Some are hidden within decrepit buildings atop rickety staircases, like Pithecanthropus Erectus in Tokyo’s Kamata neighborhood or Ragtime in Setagaya. Others are steeped in lore that’s tied to their regional location: Nefertiti in Chiba, Rondo in Akita, Jazz Inn Okura in Kumamoto, or Ray Brown in Iwate.

Finding these places is no easy feat, which makes the efforts of James Catchpole all the more remarkable. An affable writer and broadcaster from New York, who worked with Arneill on Tokyo Jazz Joints, Catchpole has been exploring Japan’s jazz scene for around two decades. During this time, he created the de facto English-language guide to the jazz kissa, bars and clubs in the Tokyo metropolitan area, called Tokyo Jazz Site. It’s a great starting point for anyone who wants to explore the domestic jazz scene.

However, the thing is, you don’t need to be a bona fide jazz expert to enjoy the kissa experience. I can tell you very little about the under-appreciated artists who belong in the canon and know even less about saxophone ranges, bass chord progressions, or the transition from swing to bebop. It is in the unknown, the chaos, the embracing of entropy in jazz — and the kissa that celebrate it — that one can find the beauty. This explains Japan’s relationship with jazz as well.

Japan has been shaped by social conformity, while jazz flagrantly disregards this kind of convention. This is in part what makes kissa so special: they stand in contrast to the often orderly and pristine streets surrounding them, venerating a musical language in which the rules are both loose and there to be broken. They represent the desire for self-expression that is fundamental to being human. Jazz and freedom, as Thelonious Monk once put it, go hand in hand.

All images courtesy of Philip Arneill / Tokyo Jazz Joints 2023. Check out Tokyo Jazz Joints online or on Instagram at @tokyojazzjoints.