I am not typically given to romantic proclamations about transport. But when people from abroad ask me about Tokyo, it’s only a matter of time before I gush over the trains.

I know I’m flirting with cliché here, but I’ll say it anyway: Tokyo’s rail networks are shining examples of fine-tuned efficiency. The trains are not simply a service that helps society function, they are a foundational cornerstone of Japan’s post-industrial landscape. The one congruent thread in a decentralized city that feels otherwise vast and unevenly designed. And let’s not forget how reliable they are, rumbling into the station right on cue, waking snoozing commuters with their familiar jingles and cocooning passengers in ambient silence as they move from one destination to the next.

This brings me, in a somewhat unwieldy manner, to the topic at hand. The trains are so central to urban life in Japan, so inextricable from most inhabitants’ day-to-day experience, that to see them used as a venue for violent crimes — as happened again last month on a train in Osaka — is to witness attacks on Japanese society itself.

Terror on the Railways

The Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attack of 1995 remains the most terror-inducing incident to take place on Japanese trains. Featuring a backstory plucked from a Hollywood brainstorming session, it involved the devotees of a near-blind yogi with a Christ-like beard, Shoko Asahara, who recruited members from Japan’s elite universities using the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism, Christian millennialism and Nostradamus. The perpetrators released sarin, a chemical weapon created by the Nazis, killing 14 people and injuring up to 5,800 in five coordinated attacks on three Tokyo train lines. There was an appropriate level of symbolism too: using a deadly nerve agent to strike the central nervous system of the nation’s capital was a metaphor that required little decoding.

The attacks of recent years may not have been quite as dramatic. But even so, their increased frequency and brutal nature are a little worrying.

In August 2021, a 36-year-old man went on a slashing frenzy on a commuter train in Tokyo, injuring 10 people, which led to an hours-long manhunt culminating at a convenience store in Suginami. He later said he felt rejected by society and had desired to “kill a happy woman for the past six years.”

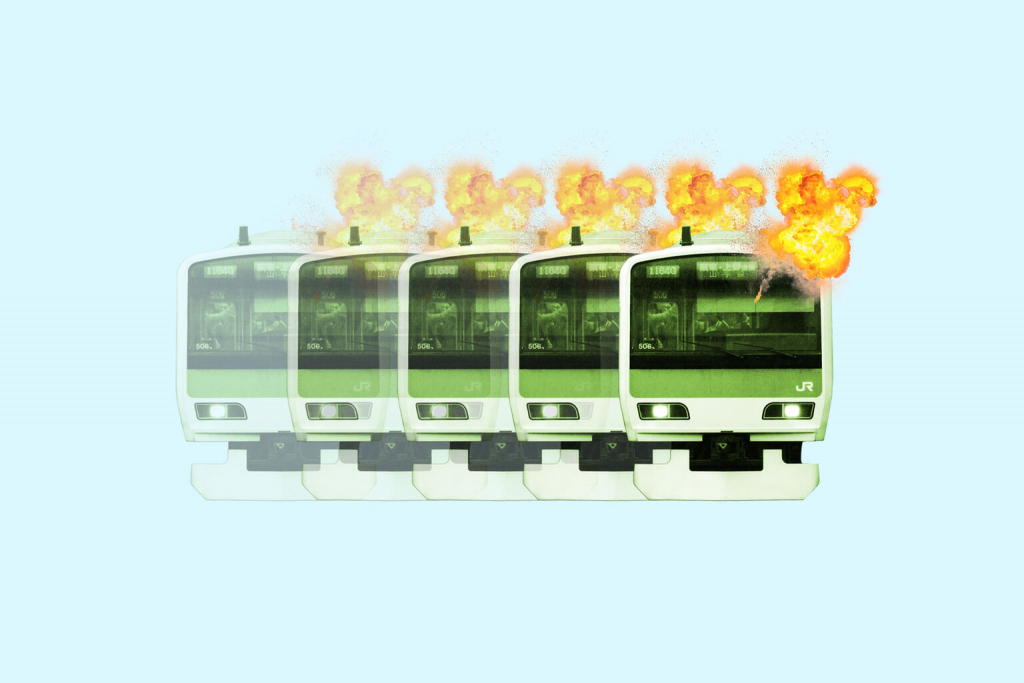

When a 24-year-old man dressed as the Joker, the eccentric villain from the Batman comics, set fire to a packed train on the Keio Line on Halloween night the same year, commuters fretted over whether railways were still safe to use, while media speculation was rife about potential “others out there like him.” Such speculation proved prophetic when a copycat attack took place on a Shinkansen a week later as a 69-year-old pensioner tried to set fire to the train using lighter fluid and a receipt, later telling police officers he “wanted to imitate” the Joker.

Following the most recent train attack in Osaka, in which three people were wounded with a knife, speculation has turned to why this keeps happening, and what Japan can do to prevent it.

Cast Adrift from Society

The recent attacks have two obvious commonalities: their setting and the aggrieved male perpetrators. Violent crimes committed by antisocial “loners” in public spaces provide fertile ground for debate. One could draw on Sigmund Freud’s model of the id (primitive instincts), ego (reality-oriented consciousness) and superego (morality and conscience), which pits the self and society in constant conflict. Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the “will to power,” suggesting individuals commit crimes to assert dominance over others, offers another interesting thought experiment.

Social outcasts are not a new phenomenon in Japan. We see it in the prevalence of hikikomori, the rising number of suicides nationwide, Japan’s low social capital ranking in the Legatum Prosperity Index and the fact that the government employs a cabinet minister tasked with combatting loneliness.

Shock value also plays a role in these crimes. The Joker attack captured the imagination more so than others, partly because of its attention-seeking, cinematic design. He may not have killed anyone, as was initially intended, but he managed to create a memorable scene, inciting fear in his fellow train users as they scrambled out of the half-opened windows to escape the flames and billowing smoke. His name was subsequently splashed across the front pages, lending credence to his actions.

This is why some analysts predicted a copycat attack in the following days. Publicizing detailed information about a crime alongside the criminal’s name is tantamount to celebration; projecting their name in lights, giving them the kind of social recognition and status their prior behavior had never warranted. And where better for a like-minded criminal to generate such publicity than on the train? That most familiar facet of modern life, ferrying millions of potential victims across the country, every single day, without fail.

Train attacks are not opportunistic, random or the machinations of people with psychopathic tendencies. They’re typically planned in advance, inspired by those that came before them and preceded by aberrant behavior, or “pre-incidents.” Some of these are transparent, such as posting threats on social media or online forums. Others are more opaque and manifest in the form of suicidal tendencies which are later directed outwards.

Increased surveillance is unlikely to deter criminals who want — who need — their crimes to be witnessed. But you can’t just profile every male citizen on the fringes of society, either. Only by addressing the root cause — social isolation — can Japan provide the best safeguards against train attacks in the future. Unfortunately, that task looks as insurmountable as ever.