For most international families living in Japan, the question of whether they should send their children through the Japanese schooling system or an international — or an alternative (does that exist?) — is a common topic of discussion and one they are most likely to struggle with. Each system has its obvious benefits: a regular Japanese school would offer a Japanese native environment and culture, where children can grow within, along with their peers. The children would enjoy joining club activities and find many Japanese friends. When it’s time for the university exams, the process of applying and enrolling would likely be smoother. On the other hand, international schools offer diversity; their curriculum calls for an open mind, and they have a global approach to many subjects — something that Japanese schools are often criticized for lacking. So what is the best approach? And what aspects should parents consider first when making this life-decisive choice on behalf of their young children?

I came to Japan in the summer of 2001, at the age of 15, and got immediately enrolled at a public international Japanese high school, jumping straight into the Japanese education system with no mental or physical preparation whatsoever. At the time, I spoke not a word of Japanese and did not know what to expect. The positive person in me imagined that my experience would be similar to the ones I had seen in movies — the new girl transferring to a new school, struggling at first, but eventually ends up making life-long friends and all’s well when it ends well. I imagined that Japan, being one of the most technically advanced nations in the world, would have the latest technology in its classrooms, too, and that the school would be very globally-minded. On my second day, I found myself at the school bathroom, silently crying because my entire class had gone somewhere and I had no clue where they were. (Eventually I understood that they had all gone to the gym for an orientation, which I was also told of, but had failed to understand.) I felt utterly lost, with no verbal ability to ask and no one around to help. Three years later, however, I graduated from that same school, speaking Japanese fluently (I took JLPT N1 in my senior year) and having life-long friends whom I still treasure as some of my dearest and nearest. But was I prepared to compete on a global scale? Perhaps not yet. Which is why, now as a parent of a bicultural child myself, I am already beginning to think about what system we should choose for him when the times comes. Because it makes a drastic difference.

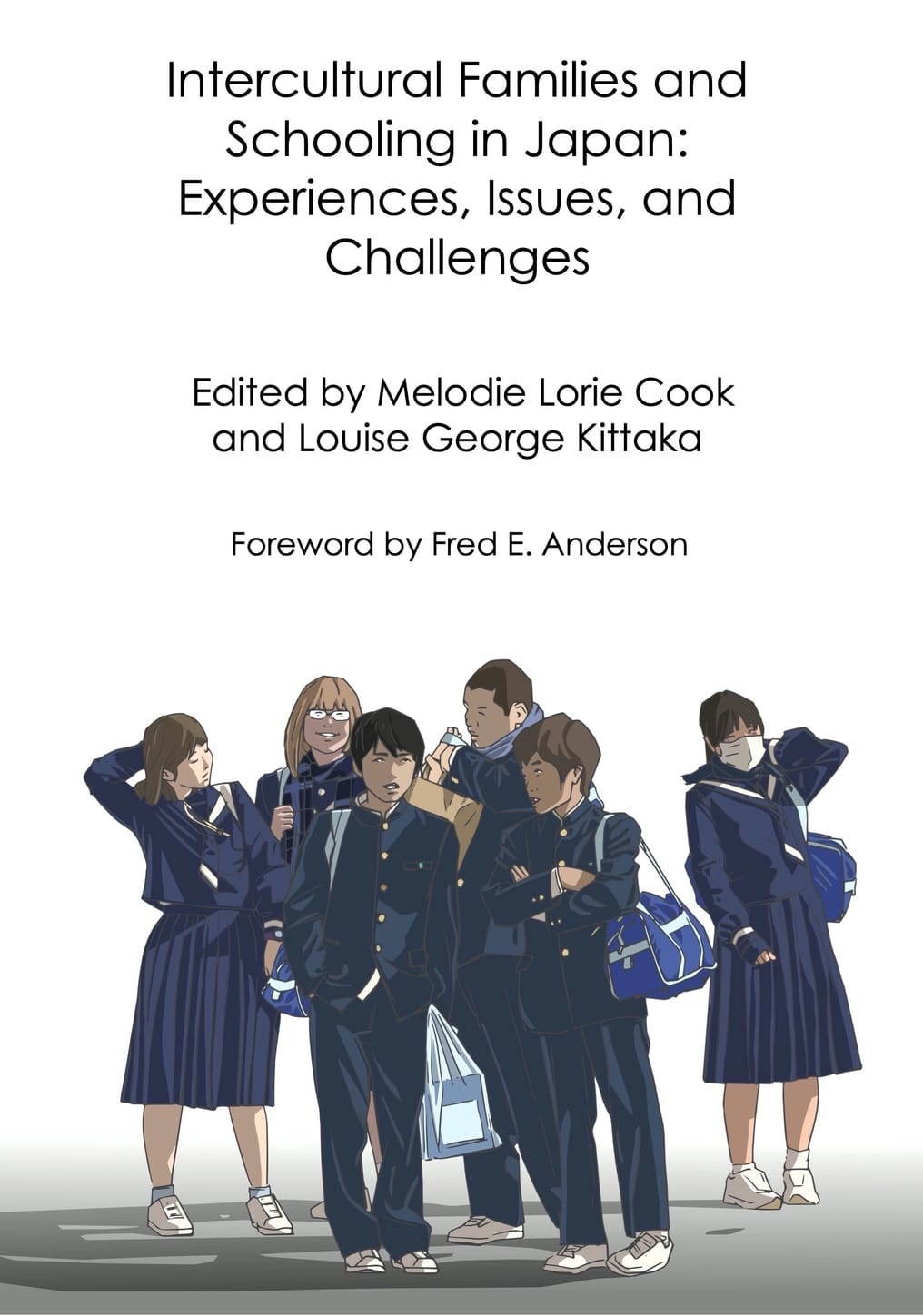

Parents who are debating what system is best for their children will then find the newly released book Intercultural Families and Schooling in Japan: Experiences, Issues, and Challenges, edited and compiled by Melodie Cook and Louise George Kittaka, two long-term residents in Japan who, as mothers, have been through these issues themselves already, of great help. The book, published by Candlin & Mynard, is an academic volume written by Japan-based international residents and researchers of various backgrounds, tackling the issues that most of us have for years had in mind, but the information was lacking. Divided into three main parts, “Finding Our Own Way,” “Dealing with the Japanese School System” and “Coping with Challenges,” the book has 11 chapters, each addressing a personal account based on experience, knowledge and suggestions from parents who have been there, done that for parents who need answers.

In “The Teacher Called me Okaasan: Experiences of a Non-Japanese Single Father With Bilingual Children and Japanese Education Systems,” single father Jon Dujmovich writes about being the primary caregiver for his two children in a system where gender roles and expectations for parents are still quite rigid, while in “An American Mother Raising a Deaf Daughter in Small-Town Japan,” author Suzanne Kamata introduces her struggles as a mother of a deaf daughter also coping with cerebral palsy. Editor Melodie Cook contributes a chapter based on her experience of raising an adopted son and fostered daughter in Niigata, Japan, by providing strategies and tips for foreign parents of similar backgrounds who are about to go through the Japanese system. Last but not least, co-editor Louise George Kittaka, ends the book with a chapter on why she decided to remove her three bicultural (and now fully bilingual) children from the Japanese system and send them to high schools in her native New Zealand.

Above all, this book is a tremendously rich resource based on real stories that we all need to hear when we make future academic decisions for our children in Japan. As Melodie writes in the introduction of the book, “there is a great need for international parents to tell their stories and share what they have learned with others who may benefit from their research.”

We caught up with editors Melodie Cook and Louise George Kittaka to learn more about the book, how it came to be and what it is trying to achieve.

1. Tell us a bit about the book — what is it and who is it for?

Melodie Cook: This book is primarily for intercultural families who are planning to send their kids to Japanese schools, although we do have chapters on sending children overseas for schooling as well. While the chapter authors are researchers, they are also parents and are writing to share their experiences with fellow parents.

Louise George Kittaka: We believe this book will also benefit anyone with a professional or personal interest in intercultural families or the Japanese education system.

2. How and why did you develop the idea for this book and what was it like to work on it? What kept you motivated?

Melodie: A few years ago, I was approached by a publishing representative who asked if I had any ideas for possible books. I mentioned that I was interested in editing a book about schooling in Japan, based on some research I had done earlier on cram schools. From that research, a lot of different issues were raised and I wanted to explore them.

Louise: The book has been more than four years in the making, and at times we wondered if it would ever come to fruition. One big issue was finding the right publisher and we went through several — including one which “lost” our draft! We were thrilled to finally find a home for our book with Candlin & Mynard, who fully supported our vision.

3. How did you two meet and what led to launching such a huge project together?

Melodie: I knew that Louise had a lot of experience writing, in a variety of venues, about family issues for the intercultural community and she had participated in some of my own studies. I am primarily a researcher, but I wanted to ground the book in reality and for it to have a practical focus, so I thought she would make an excellent partner for this project.

Louise: We are also both members of an organization for foreign women with Japanese partners, AFWJ (the Association of Foreign Wives of Japanese), many of whom have kids attending Japanese schools. From our interactions with fellow members, as well as through our own experiences, Melodie and I both know the challenges involved in navigating the education system here as a foreign parent. Melodie is a researcher and academic who also writes, while I am a writer who also teaches at university. We were able to pool our resources and strengths for this project.

4. You both have lived in Japan for many years. How has the Japanese education system changed for international families over the years? What challenges remain — if any?

Melodie: I think schools are starting to be more aware of children coming from intercultural families. There are still challenges for kids who are “different,” whether from being biracial, having disabilities, and so on. However, I think more schools are taking a proactive stance on preventing bullying.

Louise: I agree. I also think in general, there is more awareness of trying to accommodate each child as an individual, rather than just insisting that kids should assimilate for the sake of group harmony.

5. What can international families do to help make school a positive experience for their children?

Louise: Keeping the channels of communication open with your child’s teachers is key. There might be many things that surprise or puzzle you about school in Japan, but showing a willingness to listen and learn can go a long way. If there are language barriers, it is important to try and find someone who can help — a spouse, a friend, a parent of a classmate, etc.

Melodie: I think being active and creating groups with other families in similar positions is important. If kids can feel that they are not “the only one,” they can cope better.

6. How has the book been accepted so far?

Melodie: I think it’s been well accepted! We were #1 on Amazon for a while!

7. How did you collect the chapters? Did you know each contributor personally?

Louise: When we had decided on the basic concept, we put out a call for contributions and selected the chapter ideas that we felt were the best fit. Due to our connections with other writers and researchers and parents, nearly all the contributors were known to one or both of us, and we feel honored that our authors had faith in our concept. Melodie and I also contributed chapters of our own.

8. What were some of the major surprises you discovered about Japan’s current state of education by putting this book together?

Louise: I think what stands out for me is how much parents do, advocating for our kids as we help them navigate the education system here. We don’t give ourselves enough credit!

Melodie: The thing that surprised me the most was that I assumed international schools would be more accepting of and able to work with children with disabilities, since they resemble overseas schools more. However, one of our author’s children, who has autism, was refused entrance by 13 out of 15 international schools in Tokyo.

9. All proceeds from this book will benefit one specific organization. Why PanCan Japan?

Louise: PanCan Japan (the Japan Pancreatic Cancer Action Network) supports pancreatic cancer patients and their families, and advocates for better testing, treatment and research to fight this disease. Despite being the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in Japan, treatment options are very limited, since the cancer is notoriously hard to catch in the early stages. My husband was diagnosed in October 2017, and as it was caught early, he was able to have life-saving surgery and today maintains an active lifestyle. Also, our mutual friend — an American university teacher and mother — lived with Stage IV pancreatic cancer for more than four years, exploring every option and astounding her doctors with her resilience. She did much to raise awareness of the disease before she passed away at the end of December last year.

10. What is next for both of you?

Melodie: I am currently working on a new project about barrier-free learning in Japan. I hope to have another book out next year on this very important and timely topic. Although I am not an expert on this subject, working on the families book with Louise brought this to my attention and so I will be working with two experts in the field.

Louise: I always have multiple writing projects on the go and it shows no sign of slowing down. On a personal note, my middle child will graduate from medical school in New Zealand at the end of this year and I am really hoping I can be there in person to celebrate this parenting milestone.

“Intercultural Families and Schooling in Japan: Experiences, Issues, and Challenges” can be purchased from the publisher Candlin & Mynard here or via Amazon.

Tokyo Weekender Exclusive Giveaway

We have two copies of Intercultural Families and Schooling in Japan: Experiences, Issues, and Challenges for our readers. If you wish to receive a copy, please email us at [email protected] with your name, postal address and reason for wanting this book.

Updated On January 30, 2023