Healthy eating practices and veganism helped tofu gain a foothold in the West relatively recently. It started slowly in the 1960s and has grown ever more popular. However, Japan has been eating this wonder protein since the eighth century and legend has it, China has been making tofu for 2,000 years. Hence, tofu in Japan is widely available in myriad varieties. So, here is everything you need to know about tofu.

A Bean Curd by Any Other Name

Tofu is the perfect example of the key difference between intelligence and genius. Whoever came up with the idea for the soy milk-based, soft cheese-like product was definitely very intelligent. But the person who got the Western world to start calling it “tofu” instead of “bean curds” — as it was more popularly known in the beginning — was nothing short of a genius.

Though the name isn’t too appetizing, “bean curd” is a fairly accurate description of tofu. The product is created by making “milk” from soy, which is a type of bean and then congealing it using calcium chloride, calcium sulfate, magnesium sulfate or some other coagulant. This produces curds, which can then be pressed into blocks (though not always) and that’s how you get tofu. The process is almost identical to making dairy cheese. And, like its non-vegan cousin, tofu comes in many different varieties.

Types of Tofu in Japan

Simply Silk and Cotton

As with milk, the tofu section at any given Japanese supermarket can feel a little overwhelming. But, broadly speaking, there are two main types of tofu that you’ll find in a typical store. They all differ slightly depending on the manufacturer and have lots of subtypes and regional varieties, but if all you want is a white-ish block of soybean curds to eat or to cook with, your choices will mainly be silk or cotton tofu.

Silk tofu

Kinu or Kinugoshi, meaning “silk” or “silk-filtered,” is the more delicate type of tofu. It’s made by gelling soy milk to produce the curds, which are then left uncut and unpressed. This results in a silky custard-like consistency and a very smooth, light taste.

Momen, meaning “cotton,” is hard tofu, but “hard” is a relative term here. The momen variety is definitely firmer than kinu tofu, which is the result of their different production processes. Momen curds are drained, cut and pressed. However, cotton tofu is still much softer than dairy cheese and has the consistency of a thick pudding.

The More Niche Tofu Varieties

Besides those two main varieties, there is a whole galaxy of different types of tofu for you to explore. Some will be easier to find than others, like jun-tofu, meaning “pure tofu” and often found under its Korean name sundubu. Jun-tofu consists of loose, unpressed soft curds usually mixed with some kind of soup and sold in bags. Then you have the spongy koya or kori tofu, which is freeze-dried and meant for simmering. Similarly, sukiyaki tofu is pre-grilled and meant for a sukiyaki hotpot.

There’s also a whole range of flavored tofu products like edamame tofu, sesame-flavored gomadofu or yuzu tofu which is flavored with yuzu citrus fruit.

This isn’t even mentioning the dozens, possibly hundreds of regional varieties. There’s the acquired taste that is Okinawa’s pungent tofuyo, which is marinated in malted rice and awamori alcohol. Then there’s Gifu Prefecture’s firm iburidofu, made with three times more soybeans than regular tofu and later smoked using sakura cherry wood chips.

Yuba

We should also mention tofu-related products. By that we don’t mean simply other soy products, but rather byproducts of tofu-making. For instance, yuba is a delicacy that is made from the top layer of skin that forms when boiling soy milk. Okara is the soy pulp left over from a typical tofu-making process that has found its way to a number of classic Japanese dishes, as well as sneaking into favorites like donuts.

How to Cook and Eat Tofu

If you want to eat tofu as is, you should get the silken variety, cut it to size if necessary and … put it in your mouth. Congratulations, you’ve just eaten tofu. But since it has a very delicate taste, you can maybe top your second bite with some soy sauce. Add some grated ginger, bonito flakes and green onions and you’ll have the classic Japanese dish known as hiyayakko or chilled tofu. Other popular condiments for fresh tofu are ponzu sauce, sesame sauce or any salad dressing you like.

Tofu and hijiki seaweed juicy burgers

Ganmodoki fritters

Diced silk tofu cut into bite-sized cubes is also a common ingredient in miso soup, as well as stews, sukiyaki and shabu-shabu hot pots. Soft tofu can additionally be mashed with a fork and added to finely cut vegetables, which are then deep-fried to create ganmodoki fritters, though many people prefer making them with firm momen tofu. You can also take mashed firm tofu and mix it with minced meat to fry up some burgers.

Tofu is often used as a meat substitute, but it works equally well with meat. Half-meat, half-tofu burgers are one example, but you also have mabodofu, the Japanese take on the spicy Szechuan stew made with tofu, minced pork and red chili. You can easily find boil-in-the-bag mabodofu in the “ready-to-eat” food section at most Japanese supermarkets.

Mabodofu

Aburaage — Dubbed the Keto Miracle

“Aburaage” literally means “deep-fried in oil,” which is a succinct description of how this type of tofu is made. However, by keeping the piece of tofu thin, the deep-frying causes it to turn into a kind of tofu pouch which can be filled with sushi rice to create inarizushi or served on udon noodles to create kitsune udon. Thicker, non-pouch pieces of deep-fried tofu are called “atsuage.” But aburaage can do so much more and is a godsend to people on the keto diet or those following some other low-carb meal plan.

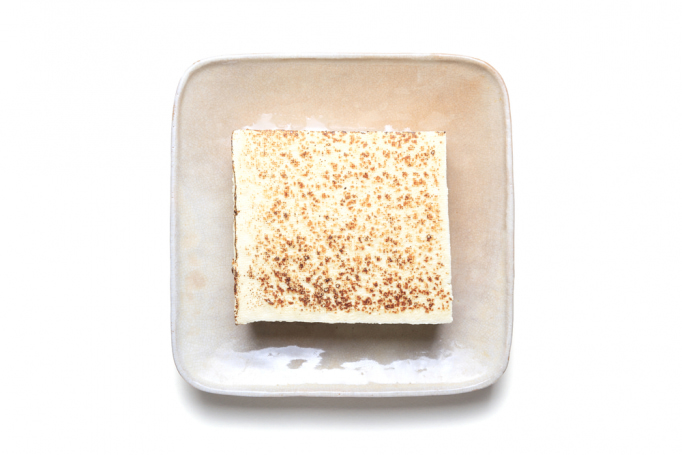

Aburaage is a cheap source of low-carb protein. You can sometimes get a pack of three for around ¥100 and the best part is that one piece can have as little as 0.3g of carbs in it. It can easily be used as a substitute in various carb-heavy dishes, like gyoza. Simply cut one aburaage in half, fill it with gyoza stuffing, close it up with a toothpick and fry it. You now have yourself some delicious low-carb gyoza. Aburaage also works as a makeshift tortilla substitute for low-carb burritos. And, when grilled in an oven, it turns crispy like a piece of buttery toast that’s perfect for making sandwiches.

What is great about tofu is that it’s so versatile, so gentle and it soaks up all the flavors. You can experiment freely and make your own recipes with it. And if you hear anyone describing tofu as bland and boring, show them this article.

Walk into any Japanese supermarket armed with this knowledge:

Japanese Milk: Navigating the Dairy Section of Your Local Supermarket

Japanese Rice: A Bite of History and Culture

Seasonal Japanese Ingredients and How To Use Them: Goya