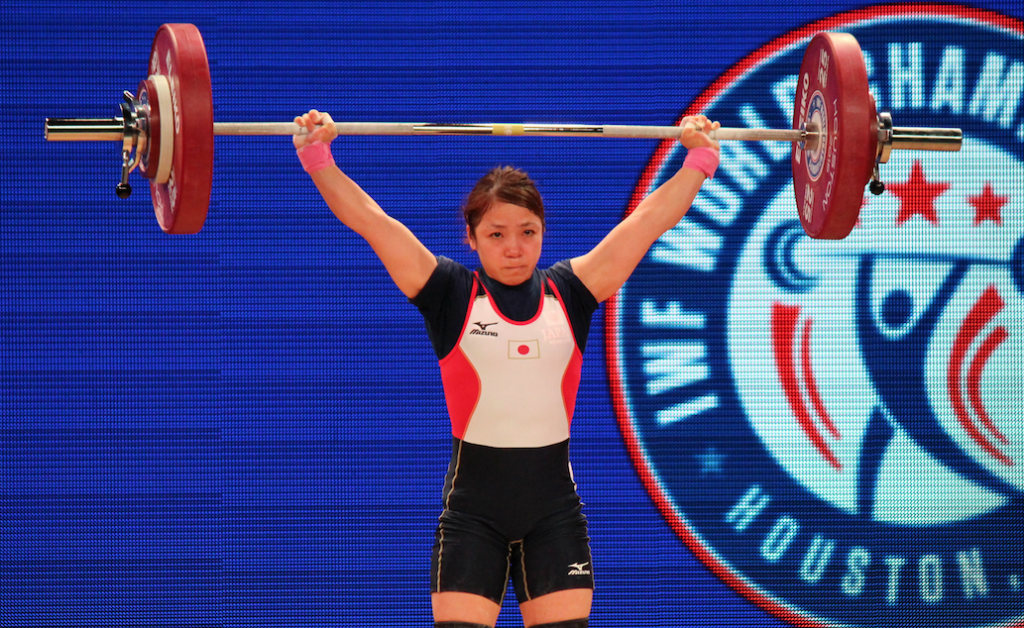

She’s the only Japanese female weightlifter to win a medal at the Olympics, and she’s even outdone her father’s bronze award. We sit down with Hiromi Miyake and her father as they prepare for the Rio Games 2016.

Following in the footsteps of a parent is never easy. When that parent happens to be an Olympic bronze medalist it’s even more difficult, yet Hiromi Miyake has done more than follow her father, Yoshiyuki Miyake. In 2012 she managed to surpass him by claiming a silver medal in the 48 kg weightlifting division at the London Games.

Now aged 30, she doesn’t have too long left in what is a physically demanding sport and as a result she’s unlikely to better her uncle, Yoshinobu Miyake, who won two Olympic golds and a silver. She is, however, capable of nabbing another medal this summer. Continuing our build up to the Rio Games, Weekender met with the Saitama-born weightlifter and her dad to talk about their careers, Olympic experiences, and hopes for Brazil.

“Growing up I thought weightlifting was too masculine for girls,” Hiromi tells us. “I focused on playing the piano as my mother was a teacher, but then in my mid-teens I realized it wasn’t for me. I watched the 2000 Sydney Olympics and just had this urge to compete even though I’d never done any sports before. Naively I thought anyone could take part [laughs]. Despite not initially being interested in weightlifting, I felt it would be the best option given the family connection.”

Hiromi was hoping her father would help, but he was initially against the idea of her taking up the sport. “I’d been in weightlifting for around half a century so I knew all about the hardships,” says Yoshiyuki. “I didn’t want Hiromi to go through that. After some convincing I eventually agreed upon one condition–that she never give up halfway.”

Yoshiyuki, who competed in the 60 kg division, suffered a number of injuries at key times during his career, most notably just before the Munich Games in 1972. World and Asian champion at the time, he believes the gold medal would have been his had he been fit enough to perform in Germany. His one and only appearance at the Olympics came four years earlier in Mexico when he finished third behind Dito Shanidze of the Soviet Union and his brother Yoshinobu, who took the gold.

“Being six years younger, I decided to let him win out of respect,” Yoshiyuki says laughing. “No, seriously, having your main rival that close makes such a difference. We really pushed each other. I managed to get the better of him sometimes, but he was a really tough opponent who broke 27 world records during his career. We looked so much alike that we’d often trick people by swapping ID cards. The greatest experience of my career was standing next to him in Mexico as the Japanese flags were raised and the national anthem played. What a moment that was!”

Hiromi had seen black and white footage of her father and uncle performing during her youth, but didn’t fully appreciate their achievements until she began training and competing herself. A late starter in the sport, her initial goal was to become a high school champion, then to compete at the Olympics. Within four years she had achieved both.

“Hiromi was in the gym every day training harder than any athlete I’d seen,” says Yoshiyuki. “As a coach I had to stop her from overdoing things. You get injuries when you’re in peak condition and continue to push yourself. Everything you do must be geared towards competition. A weightlifting event takes so much out of you physically – that is when you need to be at your best, not months earlier when nobody’s watching. Hiromi has learned this over the years and will go to Rio in top condition.”

The two of them clearly have a close bond, with Yoshiyuki spending several hours a day observing his daughter as she trains. The thought of working so closely with a family member would be considered too stressful for some, yet Hiromi takes it all in her stride. In fact, like wrestler Kyoko Hamaguchi, she seems to thrive under the tutelage of her father. “I wouldn’t have reached the level I have without my dad,” says the Olympic silver medalist. “It’s comfortable working with him as there’s a real trust between us. He’s taken me to three Olympics already and I couldn’t imagine going to Brazil with anyone else.”

Making her Olympic debut at the Athens Games in 2004, Hiromi was competing against far more experienced lifters, but still managed a top ten finish in the 48 kg category. Four years later expectations had risen. Having won bronze at the 2006 World Weightlifting Championships she was seen as a genuine medal contender in Beijing, but her father feels she peaked two months early and her lifts of 80 kg in the snatch and 105 kg in the clean and jerk were only good enough for sixth place. In London she improved those totals by seven kilograms in the snatch and five kilograms in the clean and jerk to claim a silver medal.

The 149 cm (4’9”) athlete finished 8 kg behind eventual winner Wang Mingjuan. It was the second successive victory for China in the competition following Chen Xiexia’s triumph in Beijing four years earlier. At the 2015 World Weightlifting Championships in Houston it was yet another Chinese competitor, Jiang Huihua (just 17 at the time), who took the gold ahead of silver medalist Thi Huyen Vuong of Vietnam and Hiromi who finished third.

So where does Hiromi think her biggest threat will come from in Rio? “Myself,” she says immediately. “Of course there are many strong rivals, particularly from China, but I can’t afford to think about them. In weightlifting you’re out there on your own, competing against yourself. Worrying about opponents leads to hesitation which means you won’t be able to lift properly. I have just three attempts in the snatch and three in the clean and jerk; that is my focus. What the other girls do is out of my control.”

Born to Lift

Japan has won a total of 13 Olympic medals in weightlifting, five of which belong to the Miyake family. Yoshinobu Miyake won the country’s first back in 1960, finishing as the runner-up behind America’s Charles Vinci in the Bantamweight division. Moving up a weight four years later he managed to take home the gold at the Tokyo Games and then defended his title in Mexico in 1968 – defeating his brother in the process.

A major general in the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force, Yoshinobu was known for his signature “frog style,” which was also called the “Miyake pull.” Resembling the amphibian, he adopted a wide grip on the bar, kept his heels together and spread out his knees at a 60-degree angle. He remains the country’s most decorated weightlifting Olympian with three medals, ahead of Masashi Ouchi who won a silver and bronze in the 60s. He is Japan’s only Olympic champion in the sport.

The second could well be his niece Hiromi Miyake. The only Japanese weightlifting female to win a medal at the Olympics, she once again represents the team’s best chance of a podium finish in Rio. As well as training for the Games, she also works as a coach and mentor to Honami Mizuochi (48 kg) and Mikiko Ando (58 kg), both of whom may have an outside chance of a medal in Brazil. First they have to qualify at the Japan National Weightlifting Championships, which take place in Yamanashi from May 21 to 23. Hiromi has already booked her place in the team.

The Competition

Each competitor has three attempts at the snatch and the clean and jerk. The objective of the snatch is to lift the barbell from ground to overhead in one continuous movement. The clean and jerk is two movements, first to the shoulder, then once settled the lifter will attempt to raise the bar overhead in a controlled state. The total weight of the best snatch and the best clean and jerk (out of the six lifts) will be the competitor’s total. Three judges are present to decide whether a lift has been successful or not.

This article appears in the May issue of Tokyo Weekender magazine.