During their 80’s heyday, The Jesus and Mary Chain weren’t so much famous for their music as infamous for their unruliness.

By Kyle Mullin

Chaotic violence frequently erupted amongst audiences at the Scottish act’s early live shows, as attendees pummeled each other and flung beer bottles at the band. But contrary to many naysayers assumptions, guitarist and front man Jim Reid says he and his bandmates were appalled by that turmoil, and were by no means eager to egg on the ferocious throngs.

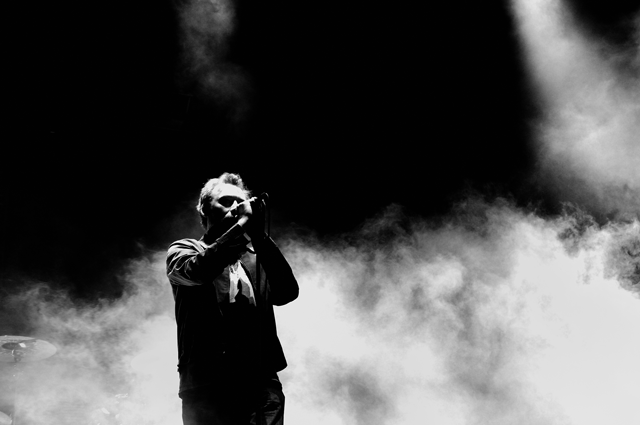

“The chaos in those early shows was something we tolerated, rather than something we orchestrated,” Reid tells The Tokyo Weekender during a recent phone interview (ahead of the band’s Feb. 26 performance at Toyosu Pit).

This is but one of the many misconceptions that have long plagued the pioneering alt-rockers. Today true fans and fellow musicians hail Reid’s live wire, feedback rife riffs as some of the genre’s most distinctive, while also praising he and brother William Reid’s mix of experimental and pop music elements. But early skeptics griped about Jim’s out of tune guitar, or laughed at then bassist Douglas Hart for having only two strings on his instrument, despite his then famous explanation: “That’s the two I use, I mean what’s the fucking point spending money on another two? Two is enough.”

Video: Early JAMC interview where Hart mentions two string bass at approx. the two minute mark

That seemingly nonchalant aloofness lead to plenty of public ire, and much of the local scene also balked at the band members’ bushy hairdos, dark sunglasses and obvious onstage drunkenness. However, that arrogant was, in part, a defense mechanism to stave off stage-fright. And today, Jim insists that their demeanor couldn’t have been more different during the sessions for their classic breakthrough album, Psychocandy.

“People thought that we were falling around drunk in the studio. But we finally had the chance to make this record, and we’d been planning it for five years. We appreciated the situation we were in,” Jim says of the all too under-appreciated work ethic that he and his bandmates employed while recording the album. He goes on to describe the dire circumstances that kept JAMC true motivated: “It was our first album, we’d just signed off the dole, we’d been unemployed and this was our chance. We understood that. Basically, we didn’t want to fuck it up.”

That meager recording budget came courtesy of Jim and William’s father, who offered 300 pounds from the redundancy pay he’d been given after losing his factory job. The brothers used it to buy a Portastudio. But just because their dad was generous, that didn’t mean he approved of their music. In fact, he was even more skeptical than their fiercest critics in the scene, according to Jim, who explains: “He thought we were going to buy a car, that would lead to employment opportunities. When he saw that we’d bought this machine to make weird noises with, he was fairly disgusted in the beginning. He couldn’t get hi heads around the idea that a band could go anywhere. To be fair to him though, if you looked around (their small hometown of East Kilbride) there was no one else doing that. No one was doing anything, other than working in factories or driving trucks.”

That blue collar melancholy is palpable on Psychocandy, with Jim’s guitar sounding like a sparking buzzsaw that he could use to grind free of poverty, or a short circuited radio that let him turn static into a rallying cry. Since then, countless angsty young bands have copied his feedback technique. Yet Psychocandy not only succeeds because of its abrasiveness. The poppy simplicity of its lyrics left many fans with an accessible hook to withstand Jim’s torrent of guitar distortion, prompting Rolling Stone to call it “bubblegum pop drowned in feedback.” Slant, meanwhile, included the album on its “Best Albums of the 80’s” list and raved: “Shaping fuzz into a potent, tactile instrument, The Jesus and Mary Chain helped establish the style of distortion-laden fogginess that would eventually become the foundation for shoegaze.”

To mark the thirtieth anniversary of that landmark album’s release, JAMC embarked on an international celebratory tour. Its Japanese leg was originally slated for November, but William fell ill with a serious stomach infection and the shows were postponed to this month. Jim is relieved that his brother has now recuperated enough to continue not only performing, but also working on the first JAMC album in nearly 20 years. They have nearly finished recording the album, and need only to tend to mixing before its release later this year.

Reza Udhin (of the long running British post-punk troop Killing Joke) will helm the album, making it the first JAMC release to have an outside producer. Jim says: “He’s a well regarded producer. We had a good meeting with him and he said he’s really been into our band for a long time, so it’s great. We also thought it would be good to have a referee to break up the fights between me and William in the studio.”

Jim is quick to point out that the tension between him and William has eased, especially compared to height of their late 90’s infighting, when the band split up.

“It rarely ever came to blows, just shouting at each other. But there seemed to be no barriers, it was no holds barred,” Jim says of those contentious days, adding that things are much less dysfunctional now because “We give each other more space, and that makes it work. We’re never going to be the best of friends, but the basis of our relationship is brotherly love, believe it or not. The line was always clear, but we just didn’t give a shit before. There is some sort of wisdom that comes with age though, and we realize we’re too old to go through the same shit we went through in our 20’s and 30’s.”

And while that wizened outlook has helped JAMC work better together, it unfortunately made them all the more hesitant to continue touring. Jim says promoters have been pressing him and his bandmates to return to the road for years, but “we kind of resisted the whole idea. I guess a lot of baggage came with the whole thing— the riot shows, it was quite chaotic and there was a lot of violence back then. We didn’t want to revisit that stuff.”

Eventually they relented and reunited in 2007 for Coachella, gradually touring more and more in the ensuing years. During those new gigs, Jim realized that the Psychocandy’s aggression and mayhem had subsided. In those early days he had to dodge beer bottles being lobbed at him by uproarious leather clad thugs descending on the stage. He says: “Back then it was a whole different landscape. Now a lot of people are coming to hear the record played who didn’t even know those incidents occurred. It’s just a lot more grown up. Now it’s more about the music than anything else.”