Some musicians tackle their inner demons onstage and in studio. When Takako Minekawa – whose collaboration with Dustin Wong has just been released – steps up to the mic, though, she’s going toe to toe with her inner sumo wrestler.

by Kyle Mullin

“The ‘sumo wrestler’ is actually a lady who is an actress, wearing a fundoshi and nothing else,” Minekawa says of one of the characters she has created over the years, with the hope of personifying her psyche’s many sides. “This sumo wrestler actress appeared in a dream once and she gave me a letter, then told me to be true to myself, to be myself.”

Such zany declarations might baffle or even alienate some collaborators, but that wasn’t the case for electro composer Dustin Wong. In fact, Minekawa’s quirks left him endlessly inspired as the pair wrote and recorded Toropical Circle, a kaleidoscopic disc brimming with endlessly pretty avant-garde melodies.

The pair met when a mutual friend introduced them after one of Wong’s solo shows in Harajuku in the summer of 2011. Wong says he remembers a “very shy” Minekawa: “We talked about my effects pedals for a little while. She gave me a CD of songs she’d done, and we exchanged email addresses.”

Before long the messages they were swapping turned from pleasantries to something deeply confessional. Wong listened to Minekawa’s amateur demo and was taken aback by her sweetly subtle singing style. But it was her self-psychoanalysis during the pair’s email exchange that truly made him want to work with her.

“That’s when she started mentioning these little people inside of her,” Wong says. “Takako talked about this little girl inside her who used to be scared all the time, but now she’s turned into a shining stone.”

“I was fascinated because I believed in a similar idea,” Wong adds. “I have different aspects of myself, I just don’t call them people, but I found that to be really charming. And the idea that these aspects could change, that really interested me. I wanted to ask her more, and try and relate it to my own ideas.”

“He’d come into my room and tell me I was playing wrong, that a song needs structure, that a punk song can only have three chords. It felt like he was trying to teach me a haiku or something.”

Wong says he was thumbing through several texts written by esteemed psychiatrist Carl Jung at the time, and his idea of multiple inner archetypes seemed quite appealing. He loved it when Minekawa told him her terrified inner child could be turned to stone, rather than haunting her until the end of her days.

Wong—who is half Chinese, half American, but grew up in Japan after being born in Hawaii— was given a far more rigid psycho-diagnosis as a child. His mother was a commercial photographer and his father directed Japanese music videos while studying psychology as a hobby. During his teenage years, Dustin would sit on his bed and noodle endless notes on his guitar in the hope of discovering his own style, before his father barged in to dictate the rules of rock ‘n’ roll.

“He had very concrete ideas of how things should be with art and music. He’d come into my room and tell me I was playing wrong, that a song needs structure, that a punk song can only have three chords. It felt like he was trying to teach me a haiku or something. I just wanted to prove him wrong.”

Ironically, by bucking against his old man’s ethos, Wong would go on to prove him right – on a psychological, if not musical level.

“Dad also studied psychology, but he’s more of a Freudian than a Jungian. Anytime someone had a problem he’d relate it to something familial or how they were brought up.”

The artistic constraints that his father laid out proved to be jump off points instead of boundaries. Wong went on to form cult art rock troupes like Ecstatic Sunshine and Ponytail in the mid-to-late ‘00s. His solo work proved to be even more esoteric, melding indie-pop with trippy avant-garde experimentalism.

“With each project I’ve worked on in the studio, I’ve broken every rule that Dad has ever told me,” Wong says with a laugh.

But, at times, Wong can be far more critical of himself than his father ever was—even while in mid-song.

“Sometimes when I’m playing I can hear actual voices within speaking to me. They can be quite critical of the performance that’s going on right then. Other times I’ll be telling myself it’s going great, then I’ll make a mistake and realize ‘Oh, the encouraging voice is actually the tricky one.’”

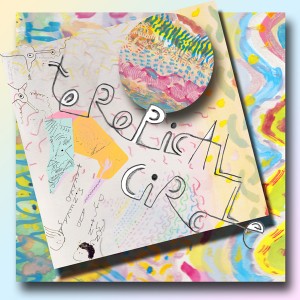

The cover of Toropical Circle, by Takako Minekawa & Dustin Wong: released May 15 on Plancha.

Wong adds that working with Minekawa on Toropical Circle helped him become better equated with those inner voices, and to contend with their criticisms.

“It helped me point them out, and sometimes that’s all you need in order for those aspects to quiet down,” Wong says of the schizophrenic tendencies that were soothed by the songs he wrote and recorded with Minekawa.

“With my past works, I was focusing on the brighter aspects of myself that weren’t so sad or angry. And as I look back and compare them to what I’m doing now, it’s apparent I’m playing in a more honest way, that I’m not ignoring those other sides.”

That by no means turned Toropical Circle into a dark, morbid affair. In fact those tense, anxious emotions provide more of an undercurrent to some of the sunniest melodies Wong has ever written.

“It was a really magical songwriting process,” he says, recalling the colorful recording session he shared with Minekawa, before describing how that magic seemed to appear before their eyes. “My parents were out of town, so we used their apartment space to record. Mom has a hula studio, it was spring and summer time, the sun was really nice. So we brought home all these prisms and hung them around the room where we were recording. Then the sunlight shone through them, so that we were constantly surrounded by these prismatic rainbows, which revolved around us while we were writing.”

Minekawa says the pair worked to capture that colorful spectrum on the aptly titled “Windy Prism Room.”

“While the colors were being overlapped on the walls of the room, my voice and Dustin’s guitar were being layered on top of each other in the air,” she says of one of the most dazzling moments they shared while recording the album.

“The prism transforms the light, the song transforms the sound. It is like a threshold when one thing becomes another. That song is, I think, about the feeling of the moment when the light is dispersing from the prism and the soft wind then spreads the rainbows around the room.”

In a way, Wong wouldn’t have minded waiting until his parents returned home to record such lush tunes. The candor he shared with Minekawa, who always had parental support as she dabbled in singing and songwriting over the years, helped Wong better accept his father’s guidance, even if it had once felt stifling.

“He likes our new songs. Whenever I play in Tokyo, he always comes to my shows,” Wong says. He adds that while he appreciates his old man’s recent, far more encouraging input, it can still be slightly confounding – in the most endearing of ways:

“Him being the good dad can be embarrassing sometimes. He’s always coming to the shows, taking tons of pictures with this really huge camera. It’s not all that hip, but I’m more than okay with it.”

Dustin Wong and Takako Minekawa play O-Nest in Shibuya on Sunday May 26 from 7pm. Tickets are ¥3,000 in advance, ¥3,500 on the door. See www.shibuya-o.com/nest or the PLANCHA site for more info or to buy tickets.

Toropical Circle is out now.

Kyle Mullin is a roaming rock journalist who has contributed to music mags around the world. You can read his interviews with Iggy Pop, David Byrne and St. Vincent, Brian Wilson and others at kylelawrence.wordpress.com He spoke with Japandroids and Rufus Wainwright for Tokyo Weekender in February and March this year.