Hip-hop has been popular in Japan since the early ’90s. Since then, homegrown Japanese artists have been creating their own genre of hip-hop incorporating syncopated American beats with Japanese lyrics. Although Black American culture has a strong influence on the music being made here, American and Japanese hip-hop are more akin to parallel worlds — taking elements from each other, without understanding the linguistic and cultural contexts of each. Caught between the cultural dissonance is Japanese-American rapper Kazuo, one of the new faces of Japanese hip-hop. His spitfire lyrics create the perfect backdrop to juxtapose the difficulty of growing up mixed and feeling like an outsider in two worlds.

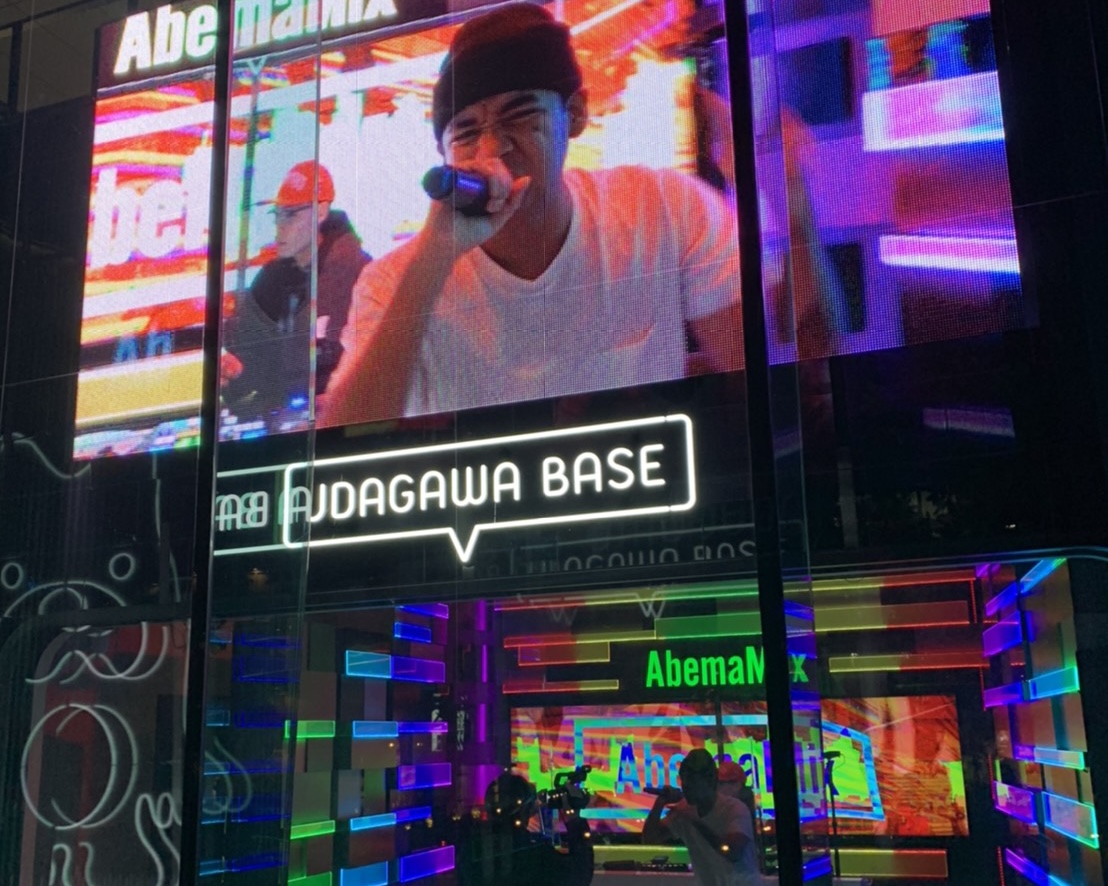

After dropping his 2020 album Akuma, Kazuo embraced his indie roots by building his following further on both his YouTube and TikTok channels where he gives a more personal account of his life as a rapper in Japan. As his stardom continues to rise, Kazuo sat down with us to discuss his journey as a bicultural bilingual rapper and how he hopes to further internationalize Yokohama and Japanese hip-hop.

1. Can you share with us a bit about your background and how you got into making music?

This has always been the hardest question for me to answer because I’ve lived in so many places growing up. Even now I can’t seem to settle down. I’m still moving around for my music going back and forth between Yokohama and New York. I’ve spent an equal amount of time in both places so they both feel like home.

I originally wanted to be a basketball player, but moving around so much made it difficult for me to be a good athlete. Music was always a constant in my life as no matter where I was I could study it.

2. Who do you consider your biggest musical inspirations?

I enjoy experimenting with music so I take inspiration from lots of different artists and genres. The first person’s discography I seriously got into was Michael Jackson. As tragic as his career was in the end, I admire his work and how he was able to connect with so many people globally. I then took inspiration from ’90s hip-hop, ’80s hardcore punk rock and even K-pop. Listening to Korean rap specifically and artists like Flowsik is what made me start writing bilingual lyrics. Especially since we have similar backgrounds. He’s a Korean-American who grew up in New York and made it big in Korea through his music.

3. How did you get your start in music and why did you choose to remain independent?

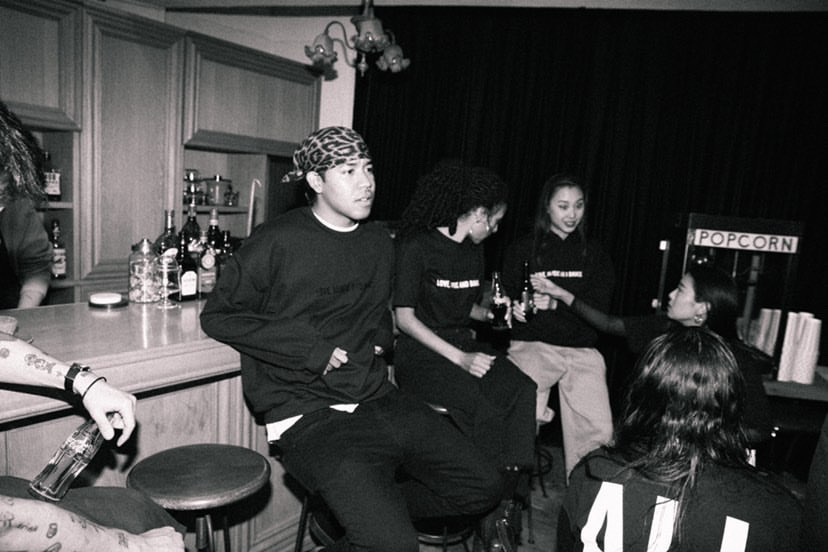

I got my start in New York doing open mics, little showcases and house parties. Now I’m getting booked for shows in America and Japan. I’ve been independent since I started and while it’s great, it’s a lot more work than most people imagine. Signing with a label gives you access to a built-in network of people which is good. But that also means you’ll likely be limited by what you can do creatively.

Being independent means I retain creative control and I’ve been able to work alongside labels and other signed artists without being limited by a contract. That’s not to say I won’t ever sign with one but I haven’t had a deal offered to me that made me feel like it would be worth it.

Of course, you can’t do everything by yourself. I do have a team of people who represent me in the spaces I can’t reach on my own. They’ve helped me get my music out there on shows like NCIS and into Big Echo Karaoke. Again, it’s a lot of hard work but I’d honestly recommend any artist to be independent.

4. Who are some of the artists you’ve worked with?

I prefer working with artists who aren’t similar to me. I prefer collaborating with artists that can bring something new to the table that I can’t do. I’m currently working on some collaborations with a few singers like Shima and Celeina Ann. Eventually, I’d love to work with singers such as Hikaru Utada, Thelma Aoyama, H.E.R. and Jhene Aiko.

5. How would you describe your musical style?

I like to experiment, so it’s hard to put a label on my style. Currently, my music is the aggressive, in-your-face, angsty rap style. It’s heavily inspired by nostalgic ’80s punk rock. That’s very present in the songs I dropped this year like “Catch Me If You Can” and “Watch Out.”

For the songs I’m working on next year I want to dive deeper into creating that nostalgia for a different time but putting a different spin on things. The aggressive rap has gotten kind of stale for me, so I’m trying something new next.

6. What are the biggest challenges about creating bilingual lyrics?

Creating bilingual lyrics isn’t a challenge because that’s really a reflection of how I talk regularly, especially with other bilingual speakers. I mix Japanese and English daily with my friends and family.

When I first started doing shows, my songs were mainly in English and I had to tell people I was from Japan. But I wanted to convey that I’m from Japan in my music, so I started using more Japanese in my songs.

It’s probably more of a challenge for the listeners. Performing bilingual lyrics can create a bit of a disconnect with people who don’t understand the lyrics completely. In Japan especially, a lot of the hip-hop fans don’t really understand the English lyrics. Bilingual rapping could hinder me with some people, but those aren’t the people that I make music for.

7. Being part of the American and Japanese hip-hop scene how do you feel about the mix and appropriation of both Black-American and Japanese aesthetics on either side?

There’s a lot of mixing and appropriation going on from both sides. I don’t agree with how American artists use Japanese and other pieces of Asian culture as background aesthetics in their videos like The Harajuku Girls. However, I like seeing American artists showing their nerdier sides with references to anime and their appreciation of Asian cultures like with Megan Thee Stallion or RZA. But you can’t defend the appropriation on either side.

At times I do feel conflicted about representing Japanese hip-hop. I do want it to be big outside of Japan, but I don’t know how to do that without bringing attention to all the Japanese artists that do appropriate Black-American culture. There are some really great Japanese artists out there who don’t have locs or say the N-word, but they’re a minority within a larger group who see Black culture as an aesthetic. Some of these artists don’t recognize all the systemic issues Black people have faced that gave rise to the culture of rap and hip-hop that we know today. It’s cringy. But on my end, I try to call out artists like that and refuse to work with them.

8. Do you have any advice for people interested in making music in Japan or America?

Stay true to yourself and don’t cross any weird boundaries. You don’t need locs to make rap music or use Japanese lyrics to stand out from everyone else. Just be yourself and stay independent.

Follow Kazuo on Instagram, TikTok, Twitter and YouTube.

Read more about the music scene in Japan:

More Than Music’s Justin Sachs Hopes To Change the Tokyo Live Scene

How Miki Matsubara Became a Viral Sensation 20 Years After Her Death