It’s an easy thing to talk about putting aside the weapons of war and give up fighting. But how do you do that when thousands of soldiers—and many of their leaders—believe that a death on the battlefield is nobler than a life lived after surrender? Is such a thing possible?

By Alec Jordan

This is one of the many issues that “The Emperor in August” (Japanese: “Japan’s Longest Day”), a film written and directed by Masato Harada, seeks to address. The film looks at the final moments of World War II from the perspective of the highest echelons of Japanese society―the ministers of war, the generals, and the admirals who sent troops to fight and die, and the spiritual leader of the nation, Emperor Hirohito.

Harada is in a rare position as a Japanese director reaching out to foreign audiences: he spent several years abroad―studying and working in England and the U.S. And, although most of his professional work is done behind the camera, he has performed acting roles in “The Last Samurai” and “Fearless.” More than 25 years as a director have allowed Harada to explore a variety of stories, from the aftermath of the ill-fated JAL Flight 123 to lighter subjects. But “The Emperor in August” is his first war film.

Weekender spoke with Harada to find out more about the genesis of the project, the challenges of presenting complex history to a foreign audience, and what we can still learn from the end of World War II today.

What was it that first inspired you to begin working on a movie set during this time?

Back in 1945, my father was 19 years old and he was recruited as a student and went to the south—in Kyushu—to an airbase called Chiran, which was specialized for Tokkou Kichi (an airbase for the kamikaze attacks). He was not a pilot; he was just digging trenches. That was in August; if the war had continued and the Allied Forces had landed in Kyushu, he could have been one of the first casualties. So that knowledge kept me thinking about how the war was ended by the Emperor’s Imperial Decision.

…[But] for many years, Japanese cinema wasn’t allowed to even display images of the emperor. And that’s one of the reasons why [film director Kihachi] Okamoto couldn’t show the Showa Emperor in the way he made “Japan’s Longest Day” in 1967. I started thinking about making a proper version of “Japan’s Longest Day” later, in the late 1990s/early 2000s. But still, 10 years ago—the 60th anniversary of the end of the war—I started thinking that it was time to make a proper film that portrayed the Showa Emperor. But some people around me said, “don’t do that; it’s still a risky business.” In 2006, the Alexander Sokurov film, “The Sun,” was released in Japan. And still, many theater owners feared right-wing attacks. It was only shown at a small theater in Ginza and my wife and I were one of the first audiences in the cinema. It was sort of an intense feeling: Everyone who was waiting in line was worried that something might happen, but nothing did. But I felt really frustrated by Issey Ogata’s portrayal of Emperor Showa, because he mimicked the habitual gestures that Hirohito would make later in his life. In 1945, he didn’t even do those sorts of things. In any case, even if he did have those kinds of habits in 1945, it’s not so graceful to show him like that.

I don’t think it was Sokurov’s idea, but rather Issey Ogata’s decision because actually he is good at mimicking people and always he can portray a banker, or different writers—he can portray people from all different backgrounds in distinctive styles. And in case of the Emperor, he came up with the idea (always saying “ah-so”). I just simply see it as an over-the-top performance.

Much of the portrayal of Emperor Showa comes from the books written by left-wing scholars, and they always criticized Hirohito’s war responsibility, so I needed to make a film which fairly portrayed the Emperor and also the character of Korechika Anami (the War Minister of Japan), Prime Minister Suzuki Kantaro, and then that era—the intense last four months of Imperial Japan in 1945.

One of the more pivotal scenes in the movie takes place between General Hideki Tojo and Emperor Hirohito. Knowing the Emperor’s interest in the natural sciences, Tojo uses the analogy of a turban shell in a report that he delivers—he is trying to persuade Hirohito to reject the idea of surrender. In response, the Emperor strikes back: he responds with a warning about Napoleon’s great deeds in the first part of his life, and his selfishness in the later part. Effectively, it’s a slap in the face. What gave you the idea for this scene?

Tojo’s report is true—He said exactly that, but nobody knows how Hirohito responded. But … right after that meeting, Tojo stopped complaining about the accepting the Potsdam Declaration, and he became quiet and followed whatever the Emperor wanted to do. So, I imagine that it must have been some kind of harsh treatment or a reprimand or something like that. My image of Hirohito is as a witty, educated man . . . he really loved the lives of great European historical figures, and he thoroughly appreciated British style and humor.

Also, he was greatly influenced by Lord Saionji [Saionji Kinmochi]. Lord Saionji is known as the last genro—a noble statesman. Saionji was fluent in French and English because he was educated in France for about 10 years when he was young. And later on he became an ambassador to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Germany, and Belgium— so he was very westernized. He was a teacher to the Emperor and he showed him what to do and not to do. I think that Emperor Hirohito inherited some kind of humor or that kind of manner from Lord Saionji.

And for Tojo, during the speech, the Emperor takes a seat [the Emperor would usually stand when receiving reports, so for him to sit down while speaking to Tojo is a clear signal]—it was a really bold move and it was something direct and confrontational that I wanted the Emperor to do. That’s my sort of a new image of the Emperor: probably even for most Japanese. For me, that moment is a core of the film.

Of course, war is a thing of deeds, but beginning them and ending them is very much a thing of words and and specific language. For example, people will be paying a lot of attention to the specific words that Abe-san uses in his speech on the 70th anniversary of the Japanese surrender, or about the specific words in Article 9. Several key scenes focus on English-Japanese translation, and on the specific wording of the Emperor’s surrender broadcast. I wonder if you saw any connection between those scenes and the present day and this focus on language.

I think that’s a problem of Japanese mentality. It’s about not seeing the forest for the trees when you’re picking at those words. And the problem of Abe is changing some wording and he thinks he can hide his true feelings, but already a problem is revealed. He doesn’t realize that.

Back in 1945, the Emperor reprimanded two chief members of the council—the Minister of the Army and the Minister of the Navy—because of their fixation on the wording. He clearly said “the wordings doesn’t matter! We just have to finish it. Don’t go picking at the each word!” It may not have been exactly those words (laughs), but that was what the Emperor actually expressed.

So I thought it was really ridiculous that Japanese translators were desperately picking away at how to translate the phrase “subject to.” [“The authority of the Emperor and the Japanese Government to rule the state shall be subject to the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers who will take such steps as he deems proper to effectuate these terms of surrender.”] … Relations have always been difficult because of those communication problems. That’s why a guy like Saionji is really important because his perspective could be summed up this way: “Healthy nationalism is fine, but in Japan, we Japanese have a lot of problems because of our Japanese-centered nationalism. We never think about other countries’ nationalisms.”

After the Emperor’s speech was recorded, there was some worry that the record would be destroyed in the coup. A member of the Chamberlain helped keep the record safe, and a female worker at NHK stands in the way of Kenji Hatanaka when he tried to make a broadcast that would help support the coup attempt. What was the purpose of dramatizing the deeds of these less powerful people?

I wanted to make a point about general people’s reactions. It is not always about decision makers. In reality, she actually did that. She was just a worker at NHK, and yet she took her own risk and then shut off all the electricity—that was a reality and I thought that it was a really courageous move. And I thought other people—announcers and technicians inside the studio—would have had the same kind of feelings—sort of a resistance for a moment.

This is not a story where you are expecting to find any “winners.” But Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki does seem to be one. Do you see him as one of the few people who come out ahead in this film?

Yes. I respect him for what he did and what he didn’t do. I think that was the only way for him to meet the Emperor’s expectations. He couldn’t shorten the process. It took that kind of time: he needed to spend some amount of time to talk with the cabinet members. Of course, in this movie, it’s not included, but actually, there is an argument in Parliament before that. There were a lot of complicated arguments, but Suzuki was always waiting for right moment to come to a decision, and then finally lead everybody toward seeing that the Emperor’s Imperial Decision was inevitable. I think he was a brilliant politician and also a gutsy Navy Admiral—he was a good fighter, I think. Without him, I don’t think the Emperor could have made the Imperial Decision. He was a key figure.

Anything that you really want a foreign audience to take away from the film?

My films contain the very contradictory American ideas that “Things don’t work out,” “It hardly matters” “Grace and self-reliance are more valuable than gold” and “home and honor are the most valuable of all.” With that kind of approach, I made this film—so that Western audiences could share the ambivalence that Anami went through, and come to understand Anami and Suzuki, and Hirohito’s feelings about home and honor. I think that is something that could be shared with every race and every country.

I also want people to just forget about the Wikipedia idea of Emperor Hirohito. Just look at him fair and square. He was enduring for about 15 years—since Japanese armies invaded China and started Manchurian Incident. He was always looking for the time he could bring an end to the war.

That is the kind of message I wanted to show, and also I hope this is one of the first films I make about World War II. I want to make film about 1942 and another about the Potsdam Declaration and the Potsdam Conference itself—especially the battle between Truman and Stalin. I was asked at the FCCJ screening: “why do most Japanese directors make war films from the point of view of being the victim?” I hate those Japanese films. If I were to make a film about the atomic bomb, I don’t want to make a film like Shindo Kaneto did in 1953. In 1953, that might be necessary to show—just before the bomb drops—so many childrens’ innocent lives. That’s too innocent today. If I am going to say about the how bad these ugly bombs were, I’m going to make a film about the Potsdam Conference and how Truman and Stalin and Burns decided to do that: that kind of human drama. At the same time, I want to show Japanese armies’ wartime atrocities in Southeast Asia—and actually I am preparing for that. So, I want to show both sides. This time, I stayed with those Japanese souls, particularly my favorites Suzuki and Emperor Hirohito—those are my heroes in this case. But tomorrow, maybe I’ll accuse that Japanese militarism!

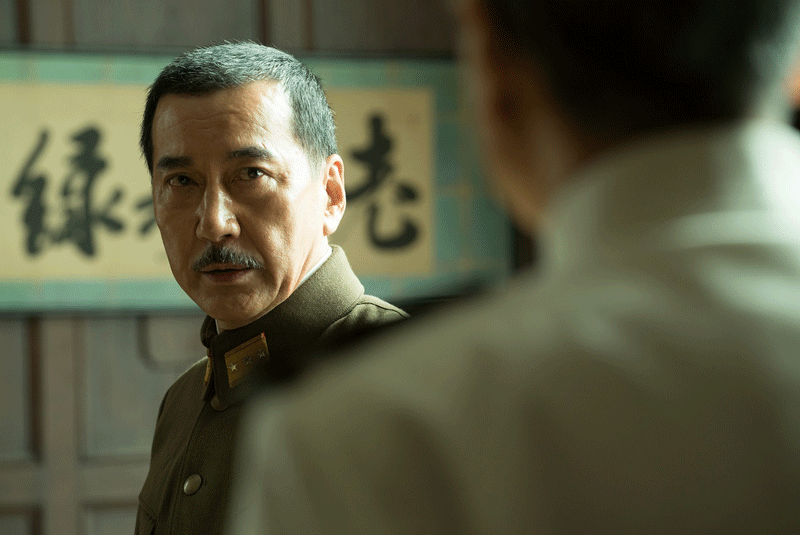

Main Image: War Minister Korechika Anami, portrayed by Koji Yakusho. All images courtesy of Shochiku Films