Widely considered one of Akira Kurosawa’s greatest movies, Ikiru (To Live), released in 1952, tells the story of a civil servant with terminal cancer who tries to make up for lost time and lead a life worth living in the final months of his life. The 2022 British remake of the film, Living, which only premiered in Japan on March 31, 2023, tries to do the same but stumbles right out of the starting gate. Here are some of the low points of the film’s 102-minute-long journey of baffling stylistic and plot decisions.

Living in the Worst Possible Time Period

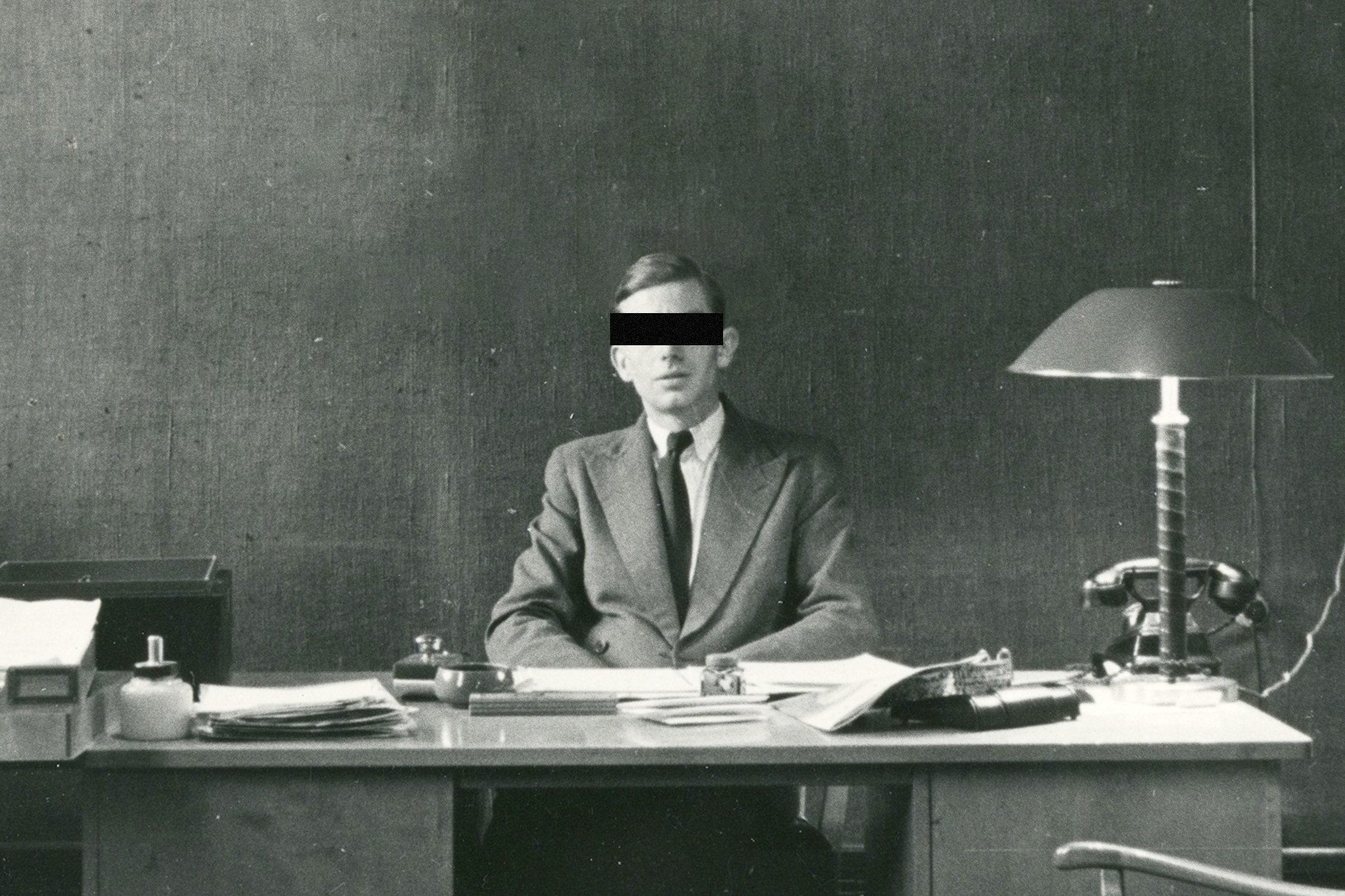

Directed by Oliver Hermanus and starring Bill Nighy, Living takes place in London in 1953, so at almost the exact same time as Kurosawa’s story. It’s the worst possible setting the movie could have chosen. By taking place 70 years ago, Living becomes a period piece, which Ikiru definitely was not. The Japanese film was contemporary, dealing with and skewering issues that cinema audiences of the time could identify with. However, some might argue, just like how many elements of Ikiru have remained relevant to this day, from bureaucratic inefficiency to generational conflict, so can Living address the problems of the present from the past. And that’s true. It can. But it doesn’t.

At best, Living merely copies the most satirical and heart-wrenching elements of Ikiru, but it doesn’t do it well, especially with the runaround given to a group of concerned mothers trying to get a neighborhood cesspool replaced with a playground. In the Kurosawa movie, the ladies being sent from one department to another is fast, frenzied and almost Kafkaesque. In 2022, those same scenes were slowed down considerably, completely taking the sting out of them. As for scenes of generational conflict, they are so short as to basically not be there in the British film.

To Live Is Timeless, Living Already Feels Dated

Living stars Nighy as Rodney Williams, a senior London County Council bureaucrat with plenty of disposable income, who can come and go to work whenever he pleases without worrying about losing his job. Not exactly the most relatable character. Ikiru’s Kanji Watanabe (Takashi Shimura) was similarly a middle-class paper-pusher with job security, but that reflected Japanese reality back when the movie came out. Maybe things were the same way in London in the 1950s but that is no longer the world we live in now. Nowadays, from the U.K. to the U.S., people often need 2-3 jobs to barely stay above the poverty line, finding themselves working harder and harder each year to not sink below it.

To make an authentic remake of Ikiru, you really need to set it in modern times, not just because Ikiru was a modern film when it came out, but because the 2020s are the perfect target for an examination of the emptiness and meaninglessness of work that would allow any movie to still be Ikiru in spirit while at the same time, doing its own, original thing. In contrast, by not doing that, Living’s connection to Kurosawa’s work can only ever be surface-level at best. Sadly, that’s still not the biggest problem with the movie.

Life Isn’t Pretty, Living Pretends That It Is

Ikiru was no stranger to spelling some things out, like how its narrator gave the audience a quick explanation of who Watanabe was as a person. But when it came to the important moments, the movie kept quiet. Living does the exact opposite of that. Instead of a finale without narration, the British film ends with a voiceover by Nighy explaining that him choosing to fight to get the playground built is the true meaning of life. Because even though it wasn’t anything important in the grand scheme of things, it was something that he put his heart and soul into. It was meant to be a touching, beautiful moment. Ikiru plays it differently, starting out with a bunch of self-centered bureaucrats insulting Watanabe at his own wake.

They eventually get drunk enough to admit that, maybe Watanabe was on to something with this wild idea of “helping people” and they vow to be more like him, only to forget about it the following day. It’s an ugly, sweaty, messy scene full of unpleasant people. This makes you wonder what the main character really accomplished. He will be remembered in the neighborhood he helped improve (for a while at least) but he also annoyed a lot of people above him, something beyond a faux pas in the heavily-hierarchal Japanese society.

Furthermore, his family still doesn’t get who he was and, ultimately, he dies alone. Yet he dies content because he passes away in the middle of the playground he helped build. Was it worth it? In Ikiru, the answer is left for us to ponder on our own. In Living, the answer is “Yes, yes, a thousand times yes, and it’s all just so beautiful, please cry now.”