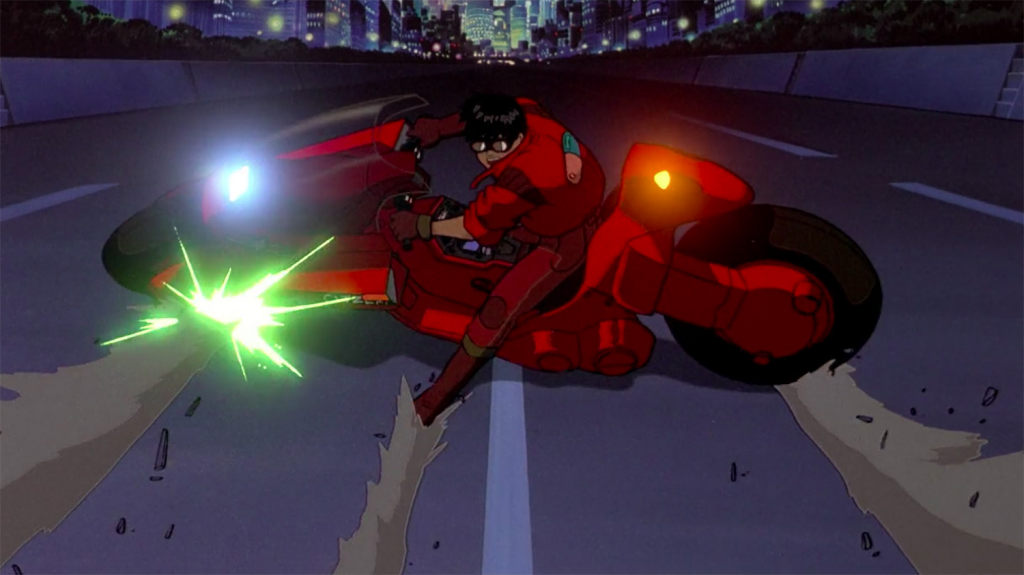

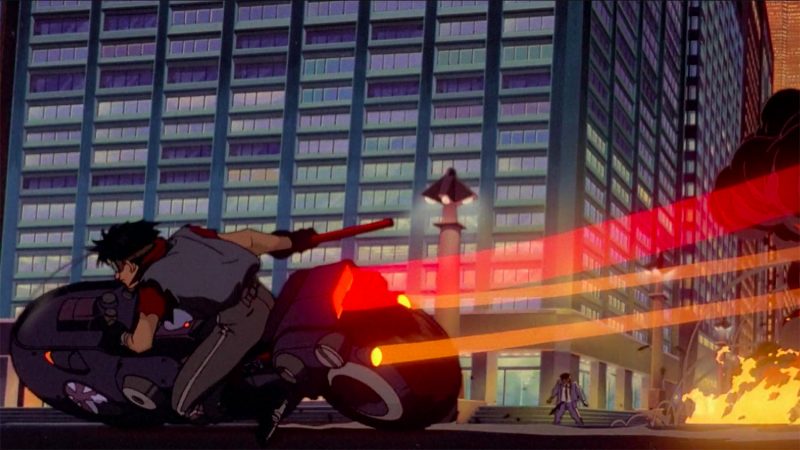

Near the beginning of the iconic Japanese animated film Akira, a motorcycle gang flies through the streets with engines revving, their tail lights leaving trails of light in their wake. Brandishing steel pipes and Molotov cocktails, they create havoc — smashing windows, burning vehicles, and picking fights with rival gangs.

All of this may just seem like an extension of the fictional world that Akira builds, part and parcel for the dystopian megalopolis hellscape of Neo-Tokyo. But in reality, biker gangs really did roam the streets of Tokyo en masse in the early ’80s when Katsuhiro Otomo began conceptualizing Akira, and they were just as intimidating as the manga and the movie depict.

As Akira celebrates its 30th anniversary (as a film), much attention has been paid to the manga that inspired it and the film’s production. What about the things that inspired the manga, though? Let’s look at the history of these violent Japanese motorcycle gangs and how they brought about some of Akira‘s most memorable images.

Welcome to the Family

Known in Japanese as bosozoku (commonly translated as a de facto term for Japanese motorcycle gangs), these groups of young men were obsessed with breaking away from the conformity that held sway (and still holds sway today) in Japanese society, while maintaining a strong nationalistic pride.

The bosozoku rose from the ashes of Word War II’s kamikaze pilots, men who were trained to fight in aircraft and die honorably for the sake of their country. Near the end of the war, a large number of men were trained with this mindset, but were never actually sent out on any missions. After Japan’s unconditional surrender in 1945, these trained but never tested kamikaze pilots had trouble readjusting to post-war society.

With the occupation of Japan by American forces during the latter half of the 1940s and ’50s, many elements of America’s motorcycle and greaser culture leaked into Japanese society. The men who would eventually go on to form bosozoku already had an interest in machinery from their training in the war, all that was left was claiming a style.

The early gangs borrowed heavily from the greaser aesthetic of denim and greased pompadour hairstyles, but as the decades wore on, the bosozoku gangs began to take on a look and attitude all their own. And while American motorcycle culture was its stylistic influence, the bosozoku were always steeped in a strong sense of yamato-damashii, or “Japanese spirit.” This translation only barely scratches the surface of the context behind the phrase. It’s something that is not easily understood by non-Japanese, holding a certain je ne sais quoi that is pretty much impossible to translate.

The Rise and Fall of the Bosozoku

During the 1980s, the National Police Agency of Japan estimates that membership for bōsōzoku gangs were more than 40,000 nationwide. They were everywhere, not only major cities but also scattered across the countryside. They also frequently clashed with normal citizens and police, causing noise violations with their heavily modified rides, damaging property, and sometimes resorting to full-scale riots.

A whole host of old footage can be seen in this short documentary on the bosozoku by Vice. Members frequently clashed violently with police and rival gangs. For many of the young men who joined, a rite of passage was being beaten to a pulp by elder gang members. It’s a world that seems so disconnected from the country that is currently gearing up to welcome an influx of foreign tourists and the next Olympic games.

With such an atmosphere reaching a boiling point in the early ’80s, it’s easy to see how Katsuhiro Otomo, in creating his vision of the dystopian future for Tokyo, would extrapolate the bosozoku’s prevalence. In Akira, they dominate the police agenda and participate in anti-government riots. They make the streets their playground and balk at any authority figure standing in their way. With the way things were going during Japan’s 1980s post-war bubble economy, it would be easy to envision such a future.

However, this all came crashing down in the early ’90s with the asset bubble burst and the subsequent lost decade (the effects of which still reverberate through the Japanese economy). Memberships fell sharply throughout the ’90s. Many have attributed this to the fact that bike modifications are expensive. Coupled with the state of the economy, a lot of young adults just couldn’t afford that kind of maintenance.

Another reason for the decline of the bosozoku is the increased power of the National Police Agency. Before, police could do little against reckless driving and the breaking of noise ordinances by modified bikes. Unless the bosozoku were harming someone or destroying property, arrests were almost impossible to make. In 2004, the government revised the road traffic law, which led to more arrests of bosozoku members. For many young thrill seekers, the risks just weren’t worth it anymore.

Nowadays…

Today, bosozoku gangs still exist, but membership numbers have dropped below 5,000 nationwide. You can still hear the random biker revving through the city or across the countryside at night, but that’s about it. Every once in a while some group will try their luck creating a bigger disturbance, but these instances are few and far between – and usually swiftly handled by a now more powerful police presence.

Still, without the rise of the bosozoku throughout the post-war era, it’s impossible to imagine some of Akira’s most iconic imagery ever being put to page or screen. The prevalence of the culture in real life made a huge impact on Katsuhiro Otomo, and that lifestyle lives on within Neo-Tokyo. The world of Akira would never be the same without it.

This article originally appeared on breakerjapan.com and is republished here with permission.

Updated On April 26, 2021