You would think there is a big chasm between realism and expressionism, but Anglo-Japanese filmmaker Ryushi Lindsay proves it’s but a thin line. His short film Idol, which will be screened at this year’s Short Shorts Film Festival & Asia, is about the single mother Miyabi (Ryoka Neya) and her young daughter Kasumi (Shoplifters’ Miyu Sasaki), who is part of a child idol group. When Kasumi is replaced in the group, Miyabi must act to avoid destitution.

Lindsay’s research for the film consisted of people-watching, tuning in to the surrounding vernacular. “I would spend time listening to how people talked,” he reflected. He even attended a local idol contest.

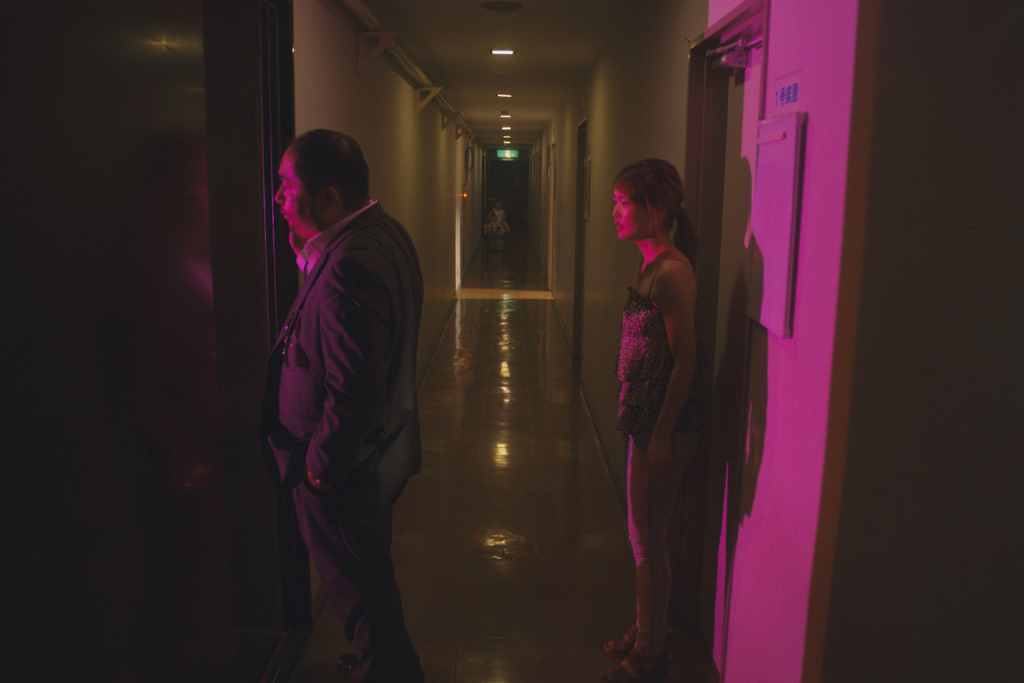

In addition to naturalistic dialogue, Lindsay and cinematographer Matt de Sousa chose to shoot wide and “[let] the frame breathe a bit” to avoid overmanipulating the images. But although the director has a documentary, Kokutai, under his belt, his aim is not to capture the world as it is – not with Kokutai, which he deems more expressionistic, and not with Idol. He talked of a deliberate unease and discomfort and claustrophobia, for example, that runs throughout the latter to engage viewers more closely with the work and, perhaps, allow them to better understand the characters.

Courtesy of Ryushi Lindsay

He deliberated again and again the way viewers consume images, what his own images say. It seems that, to him, cinema creates a mutual relationship rather than a give-and-take dynamic: every artistic choice, from depth of field to music, is not made in a vacuum, but in deep contemplation of viewer response, film theory and even his own contributing biases. After much deliberation, he offers us a film with both sociopolitical brunt and artistic eloquence.

How did Idol come to be?

It’s been a while—it must have been the beginning of 2018. I wanted to write a film that I would want to watch, and I’d been toying with the idea of something contained, with the idea of some protagonist occupying a space with a child they kidnapped. That was the very seed of the idea, then I came across this article about the murky world of child idols. The two organically grew together. That was when the script came into existence. I was fortunate to meet our executive producer through another filmmaker friend…Having done a lot of things on a much much lower budget in the past, [having an EP] just made life so much easier, and hopefully it shows in the work as well.

So the film mostly takes place inside?

That was my initial idea and it grew from that. If you watch the film, you can see that actually the scope is slightly larger. I wonder now how successful it is as a “short film” short film, in the idea of being neatly packaged. It’s more a condensed feature. At the same time, I’m incredibly proud of what we did and, clearly, we were programmed at Short Shorts and it seems to be speaking to people.

Courtesy of Ryushi Lindsay

What was your research process like for the character of Kasumi?

I watched a couple of documentaries which were rather sensationalist, done by Western broadcasters. They had their downsides, but there were some organic moments from which I drew a bit, in terms of character. Then, there was a free local idol contest in my town, so I dropped by that to get a feel of the atmosphere and see how everyone was behaving within that environment.

A lot of the character comes from the fantastic performance of Sasaki Miyu, who’s an incredible actor. I was privileged to work with her. I always believe actors have a better idea of what they’re doing than the director, contrary to what a lot of people like to say. I think actors – they’re professionals, they spend more time acting than directors do directing. So I didn’t have to direct her a lot. We talked about focusing on listening rather than “acting.” [A lot of the process] was quite organic.

There’s a slight irony in my making this film with a very successful, celebrated child actor. But the ethics of filmmaking is something I continue to grapple with, whether that’s with child actors or an adult cast or a documentary. The ethics of cinema and filmmaking is, I think, unresolvable.

Kasumi is the child of a single mother, and the family faces destitution. When I saw the film synopsis, I immediately thought of Hirokazu Koreeda and his cinema of struggling families. With this project, did his stories inspire you in any way?

I stole [Koreeda’s] cast I guess, but I love his films. I think it was less of a direct influence – I wrote Idol before I saw Manbiki Kazoku, and I think my stronger influences are British filmmakers, like Ken Loach or Andrea Arnold. But my DP Matt and I did do some research into how [Koreeda’s] films are shot.

Previously you directed a documentary short called Kokutai, about the fascist aesthetics of Japan’s national baseball tournaments. Did you channel this documentarian impulse to Idol, or was the film more a creative storytelling effort?

Idol is a hundred percent fiction, but Kokutai is not straight documentary either. I’ve received criticism for it being manipulative, which maybe is fair. At no point in Kokutai am I trying to tell an objective truth. Through score and montage, I was coming from a very specific perspective. I wouldn’t say I applied any traditional documentary techniques in Kokutai, and it leans more towards expressionism than realism. Whereas with Idol, we were trying to thread the needle between expressionism and realism.

Courtesy of Ryushi Lindsay

You have a really distinct shooting style, in film and photo – it’s like you’re examining people through their environment, or as a part of their environment. Do you make use of this method in Idol – medium-ish shots that emphasize the subjects’ surroundings? If so, how did that contribute to the film?

A big part of it is wanting to have an anti-Hollywood aesthetic, moving away from close ups and being beautiful and directing the viewer’s eye towards enjoying talent’s face for its beauty. We’re trying to move away from that, and that ties in with the theme of the film. But also I’m interested in the interplay between environment and actions, and how our environments shape our behaviors. Hopefully, giving that bit of extra room allows for scenes to be placed within an actual environment, rather than shooting all close ups with ultra-thin depth of field.

And also a big part of it was what [André] Bazin wrote about framing empowering the viewer to choose where to look and make their own stories. I’m fitting the film within a wider context of social realism, even though I wouldn’t say the film is social realist at all. Even though we did frame a little wider, I wasn’t so interested in presenting “objective reality,” as Bazin calls it. We shot the whole film on a Cineovision 18mm lens, which I found at a rental house in Tokyo – a handmade lens from the ’70s that there’s very little information about. It added a nice distortion as well; straight lines become slightly curved, and I wanted to instill a slight sense of unease throughout the film.

I think the key was moving away from dominant cinema and think more about how we’re presenting images to the viewer.

Kokutai has a really distinct soundtrack. What were your musical and/or sonic choices, if any, for Idol?

Kokutai has a very specifically modernist-classical score, without a clear melody. My composer Andrew Trewren and I focused on dissonance and expressing horror through sound – how to express the horror of nationalism and fascism. With Idol, our editor Sachi [Sasaki] and I tried a couple temp tracks during editing, but we felt it was a little too manipulative. It felt like a bit of a shortcut, like lazy filmmaking. It was doing slightly too much for us, so we took out all of the extra nondiegetic music, which I think makes the film slightly uncomfortable. It doesn’t help you a lot. I don’t want the viewer to be too comfortable watching it, and I want to encourage myself and others to consider the way we consume images of people, specifically. Creating discomfort, conscious or not, will hopefully result in some engagement with the film.

Courtesy of Ryushi Lindsay

Do you think growing up in Britain has affected your filmmaking choices?

Growing up in the U.K., I couldn’t help but be exposed to a lot of political and social filmmaking. A lot of my friends growing up were radical. I think the key influence on my work now is actually having majored in film studies in university. I was exposed to all sorts of weird and wonderful films, and film theory. I’ve encountered a lot of filmmakers and teachers of film who say that we shouldn’t bother with film theory, but I believe a filmmaker should read it. Because a lot of my work questions the world that we live in, I’m also questioning the images I create and how I represent the world. Acknowledging the influence of doing a degree in film studies means that I have to recognize my privilege as well. Being able to go to university, to even imagine being a filmmaker, I have to recognize my middle-class upbringing and growing up around artists and filmmakers.

Whether that’s in dialogue with how I approach Japan is interesting. I don’t think I can fairly assess that because I didn’t go to school here. Living in Saitama when I wrote Idol, though, there was definitely the strong influence of being in the suburbs. It feels like a different world to living in Tokyo now.

On a more meta level, I guess if you grow up mixed race anywhere, you do end up being more aware of social-political issues wherever you are in the world.

As part of Short Shorts Film Festival & Asia, Idol will be screened on September 23 at Omotesando Hills Space O; reserve tickets here. You can also watch select shorts online.

Kokutai will be screening at Leiden Shorts in the Netherlands in September.

And Blue & Yellow, a fiction short produced by Lindsay, will be premiering at the Japan Film Festival – Los Angeles in October.