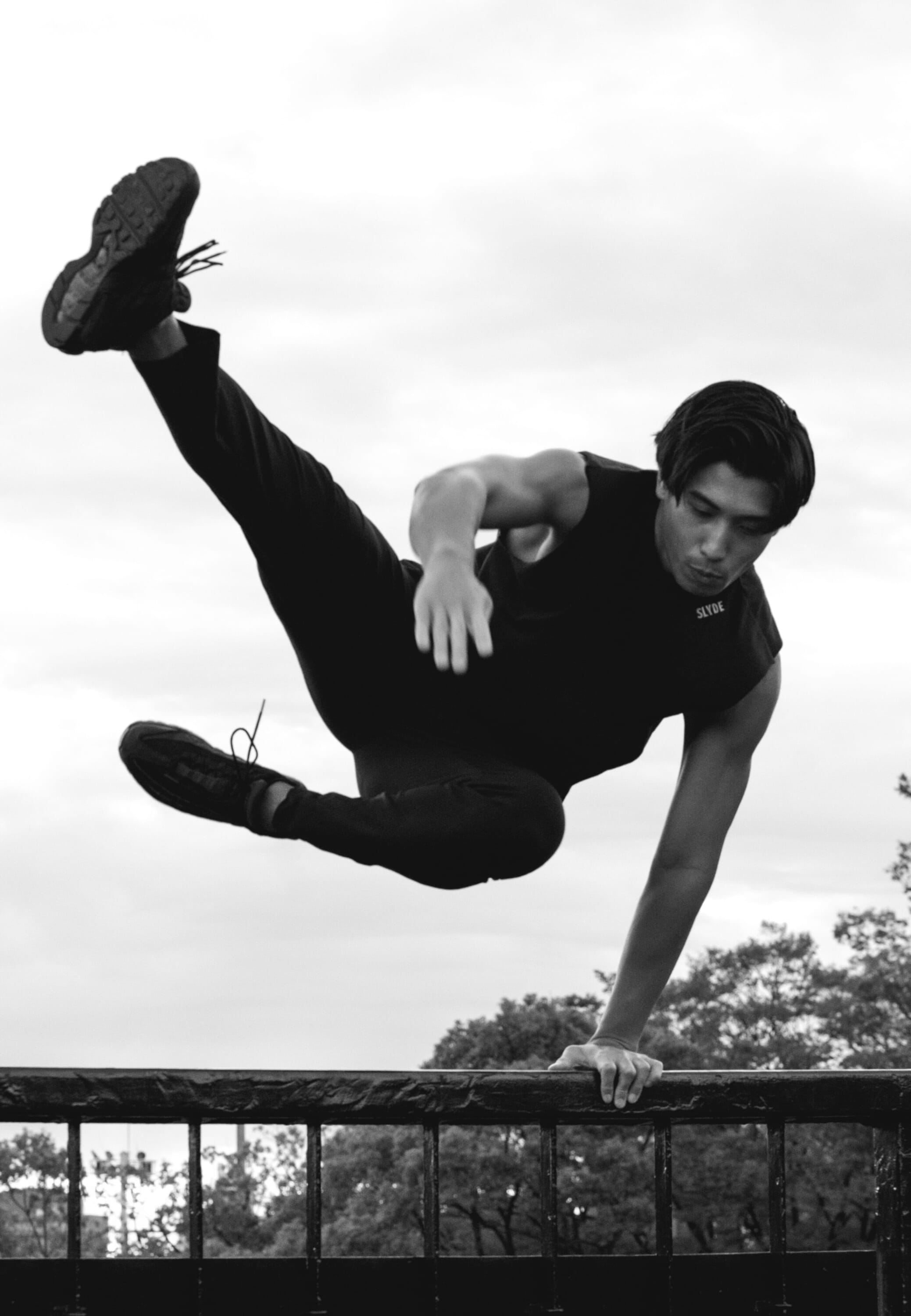

Within minutes of meeting Naoki “Nao” Yamakasi (formal family name, Ishiyama), he is upside down, doing a handstand on the rails of the bridge in Yoyogi Park. A 6-meter drop beckons on one side. For anyone watching nearby, the sight is likely mind-blowing, but for Nao, this is a regular Tuesday. That’s because he’s a practitioner of l’art du déplacement (“the art of movement”) — more commonly known as parkour.

Parkour has been a well-known sport for a few decades now. Originating in France in the 1990s, it is defined as moving from point A to point B in the fastest and most efficient way possible. This can include scaling the side of objects and buildings, jumping, vaulting, rolling and flipping to reach your destination.

Here in Japan, the sport has only started building momentum in the last five to 10 years, but Nao was hooked well before then and is one of Japan’s earliest and longest continuing practitioners.

Falling in Love with Freedom

Nao loved watching action movies, telling me, “I was obsessed with Hollywood action movies and action stars like Jackie Chan and Bruce Lee.” However, at age 11, it was a French film that would go on to influence the course of his life.

Yamakasi, produced by Luc Besson, was a film that followed a group of parkour ex- perts in Paris known as Yamakasi. “I just fell in love with their performance,” Nao says. “They were climbing buildings with their bare hands, without any safety ropes, and jumping from very high places to the ground, rolling and running, even climbing buildings just to see the sunrise.” This depiction of urban freedom captured his imagination. “I never saw this in Japan growing up,” he remarks.

Though fictional, this film used the very real Yamakasi group who founded the sport of parkour or, as they prefer, l’art du déplacement. Little did Nao know at that time just how much his own life would become entwined with this group, so much so that, as you may have noticed, he has adopted the name as his own — with their permission, of course.

From that point on, Nao started teaching himself. “I used to jump from the safety scaffolding in my school or even from the school roof,” he laughs. “I was a kid, so my body was lighter, and I was a little more stupid. I didn’t think about the risks.”

Leveling Up

A few years later, at 15, he joined PKTK, the only parkour team in Tokyo at the time. Through training with this group, he discovered he could make a career from parkour after PKTK was contacted by none other than Madonna (well, her people) to participate in one of her music videos, the 2005 single “Jump.”

“I couldn’t be in the film, unfortunately, but I was there,” he says. “I thought ‘Wow, this is so cool.’ I didn’t know performing parkour could be a job.”

At 17 years old, Nao decided to seek out the group that had inspired him to travel to Paris in the hopes of meeting a member of Yamakasi. “I heard about a famous parkour spot in Paris and headed there. I didn’t expect anything; I just wanted to try my luck.”

As fortune would have it, Nao found himself face-to-face with one of the founders of the group, Châu Belle Dinh, an individual he recognized from Besson’s film. “He was training two of his mentees in the park, and I instantly recognized him. He was standing there with a scary face, but I just ran up to him and grabbed his arm. I couldn’t speak English, so I just kept saying ‘You are Châu Belle!’” Nao recalls. “I must have looked so strange, this 17-year-old, shaved-headed Japanese kid just shouting at him.”

The stunt earned him an introduction, and, through some rudimentary communication, he ended up joining their rigorous training. One of Dinh’s mentees, a l’art du daily walking, and I struggled with this.” After a year, he had lost much of his muscle mass and was seeing little improvement, which only deepened his depression and set him on a very dark path.

“I don’t want to be too heavy, but I tried to commit suicide,” he recounts. “That day, I felt horrible; I truly wanted to die.” Thankfully, Nao is still with us. And on that awful day, he gained new clarity: “I realized I can’t die. I’m still too young. I’m only 18, and I want to do more with my life.”

Having hit rock bottom, he knew he could only go up. “I felt I could do more, maybe even try parkour again,” he explains. “I committed to doing my best. Even when I felt pain, I just pushed through it, and my body started healing itself.”

Nao describes how coming so close to death impacted not just his approach to parkour but also to his relationships: “I used to be so shy, but I grew so much through this experience. I wouldn’t say I’m fearless — fear is a natural human survival mechanism — but I now have the ability to switch it off.”

Training the Future of Parkour

Thanks to his abilities and determination, Nao has gone on to make a living from parkour, starring in a number of commercials and films for clients like New Balance, Panasonic, Rolls-Royce and Nike. He’s been in a promotional video for the film Bohemian Rhapsody and even competed against Olympic gold medalist Usain Bolt for Step App.

His main goal is to help educate people about the sport, and he spent a few years with the Parkour Generations program in London doing just that. “We were spreading information on what parkour was, how it’s not a dangerous sport if you train properly. It keeps you healthy, keeps you strong, keeps you brave,” he says. “People may think that parkour is crazy, that we are just being disruptive, but we were trying to change this image.”

He continues to teach parkour here in Tokyo with one-on-one and small group lessons to support anyone interested in trying it out. Nao also wants to reach out to people who may be suffering from depression or those who have suffered life-changing injuries in the hope that by sharing his own journey, he can help them find the same strength he did to keep moving forward.

Nao tells us that the word “yamakasi” means “strong body, strong spirit, strong people.” Considering how deeply he embodies these values, Nao is certainly more than worthy of the Yamakasi name.

Follow Nao or contact him for lessons on Instagram at @naoyamakasi.

This article was originally published in the TW November-December 2023 issue

Updated On March 26, 2024