Tomomi Adachi recently returned from Montreal after premiering an opera he composed titled Body without Organs (With Organ). But it was far from your ordinary opera: the 80-minute libretto, or text, was written by an AI program. And while human performers on the soprano and countertenor voice, violin, cello and percussion took the stage along with Adachi on organ, the opera also involved an Ondes Martenot (an analog synthesizer), an improvisational performance by the conductor, a VR headset and ChatGPT.

Adachi turned to AI to write the opera’s text for a reason. He believes that written words for a song unnecessarily amplify the emotions of the listener.

“There’s nothing wrong with writing words in songs, but it’s a dangerous part of music,” Adachi explains over a Skype interview. “If you use text written by AI, you can’t feel the emotion of the words because the emotion didn’t actually exist. So, using generated text for a song is very interesting and exciting to me.”

While the 51-year-old Kanazawa-based musical performer and composer is involved in a wide range of music, none of it falls into the realm of pop, rock, classical, folk, punk, or any other genre. He improvises with his voice in wild screams and squawks, while also putting on large-scale improvisational concerts using amateur musicians to fit the atmosphere of specific sites. He also stages performances of the works of famed experimental and radical composers like John Cage and Cornelius Cardew.

Adachi is a shining example of experimental music in an age that doesn’t have nearly enough punks and Dadaists in the spotlight — and each of his projects is more dizzying, profound and preposterous than the last.

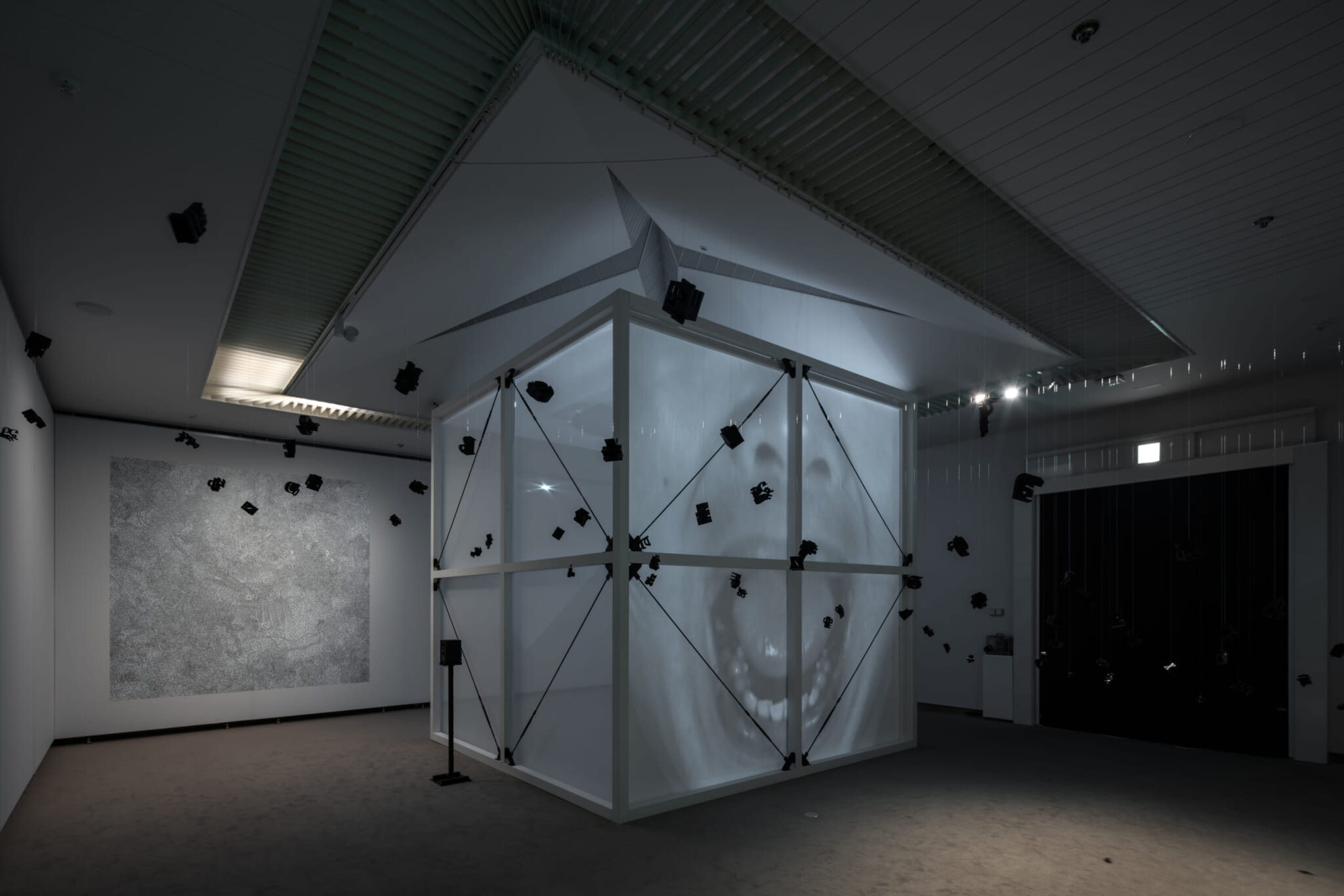

Photo by Takayuki Imai ©Aichi Triennale 2022

The Making of a Sound Experimentalist

Adachi’s journey into the world of experimental music began at 15, when he started to listen to the compositions of classical composers Béla Bartók and Igor Stravinsky.

“I just realized I should be a composer at that moment,” Adachi says. “Something opened up for me.”

One year later, he discovered the music of Cage, who continues to be a major inspiration for Adachi to this day. “I was really shocked at how music could be something that makes philosophical statements,” adds Adachi. “Cage’s music was for joy, but not only joy, and it’s hardly entertainment at all. I realized you could put your understanding of the world into music.”

In a contradictory move, Adachi started out his musical career in the world of late 1980s new wave music. It was a time in Tokyo when the border between pop and art was vaguer than it is today. Adachi remembers avant-garde saxophonist John Zorn living in Tokyo at the time and being highly active in the improvised music scene. And before too long, he found himself drifting into the world of true experimentation.

“I thought I’m not much of a pop music person. Because, you know, you have to be fashionable, especially in Japan. And unfortunately, I’m not so fashionable,” Adachi says with a grin.

Speaking to Adachi, he feels just like a friendly neighbor. But when he begins to talk about his music, enthusiasm takes over.

Pushing Sound to the Edge

Adachi’s sweeping range of activities makes it hard to encapsulate what kind of artist he is, but his essence and spirit can be seen in his vocal performances. He often performs as a vocal improviser, freely muttering, screaming, whooping, wailing, hissing, slurping and gargling in cryptic compositions alongside other daring improvising musicians.

Many of these performances incorporate electronic instruments and elements, such as his “Voice and Infrared Sensor Shirt” series. He installed 10 infrared distance sensors on his body which change his voice via a computer depending on his movements, resulting in surreal, even horrifying electronic explosions of sound in tantalizing harmony with his own frenzied movements.

Likewise, when Adachi takes on the role of composer and conductor rather than performer, his “concerts” are anything but ordinary. One show Adachi personally takes great pride in is NUo, a site-specific concert designed for a Tokyo fish market. Adachi gathered over 70 amateur performers for a one-hour show of swirling, overlapping horns, choral shouting and hollering, marching and dancing and flapping garbage bags.

“The fish market has this strange, complex structure, so at times the audience couldn’t see where the music was coming from, but they could still listen to the sound,” recalls Adachi. “It was almost like magic.”

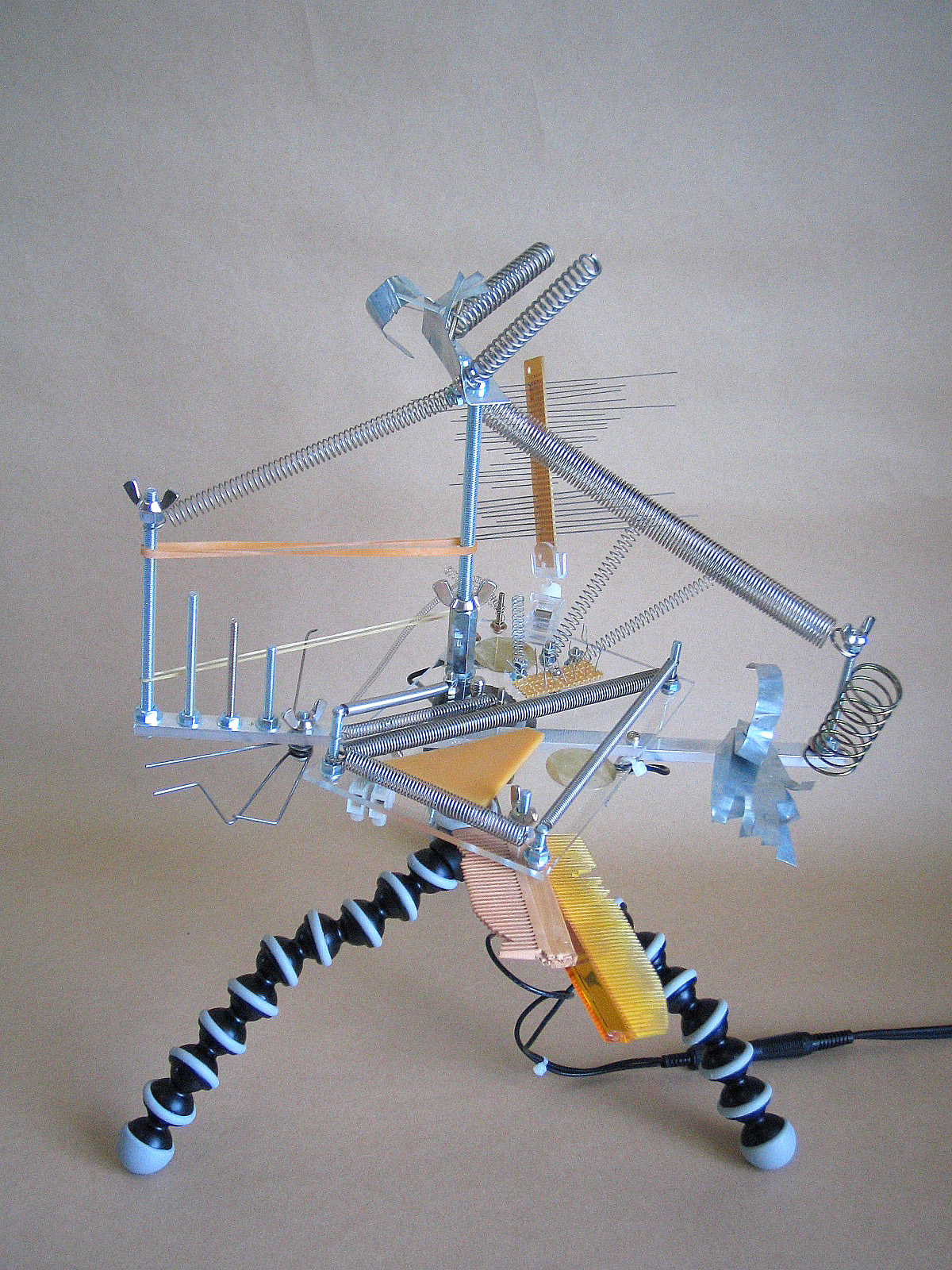

Adachi’s use of technology involves him making original electronic and acoustic instruments. This practice dates back to 1994 with his Tomomin, a one-knob, single-note oscillator covering a full range of audible sounds. He later upgraded this invention into a synthesizer and then the Tomomin II, which includes pulse, noise and drone-oriented sounds with three different oscillators. His creations also include instruments made out of living things, like his amplified giant cactus, as well as his vegetable music series that features flute-like devices made from carrots, gourds, peppers, potatoes and more.

tomoring ©ADACHI Tomomi

Next Projects and Activities

Just last year, Adachi moved back from Berlin to Kanazawa in Ishikawa Prefecture for family reasons. He says that Japan, unlike the diverse and edgy Berlin, is a difficult place to make experimental music.

“There’s no funding available and not much of an audience either,” Adachi laments. “But at the same time, a tough place makes interesting things. Tokyo’s experimental music scene is small, but the quality is very high. It’s still an exceptional place.”

At present, Adachi is working on staging a series of performances at the Japan Society in New York about John Cage’s relationship with Japan. He has also put on several shows and concerts in Tokyo. His next will be a collaborative performance with filmmaker Kei Shichiri on September 30 at the Image Forum Festival in Shibuya.

Adachi thrives living in the shadows of the world of experimentation. While he feels like the world of fine art is too authorized and marketed, experimental music scenes support welcoming and dynamic communities.

“Experimental music is a small place, but less competitive, and people make communities,” he says. “This kind of avant-garde art rarely breaks through to the mainstream, but I love the community. What I do isn’t for entertainment, it’s not for enlightenment. It’s about something in the universe that I simply believe in. My way to approach the universe.”

Updated On August 14, 2023