On the surface, the five artists do not have much in common.

Walls & Bridges – Touching the World, Living the World, at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, is a kind of five-part retrospective. The exhibition is as variegated as you would expect for this diverse group of CVs. The connections between the artists are not even readily detectable at the explicit, visual level. However, as you look, you get a feeling of accord between them. They seem to understand each other despite having never known each other.

Jonas Mekas, Oona practices violin as her cat Sunshine watches, Soho, New York, 1977. (Paradise not yet lost). Private collection.

The Diary Film

Jonas Mekas was a filmmaker from Lithuania, and his tool was a Swiss spring-round Bolex camera. Hand-shooting with this weighty 16-millimeter camera, frequent shaking and flickering is inevitable. But rather than throw away the unstable shots, he made instability an important principle of his practice, and even would designate a style called “the diary film.”

In his youth, Mekas was imprisoned in a war camp for anti-Nazi activism, and circulated through a number of refugee camps. He escaped to America with his brother. Unable to speak English, he lived in poverty. He began filming life around him and recording his poetry.

Matching the light and volatile quality of his shooting, the films are humorous, elated and warm, even heavenly. Maybe you can call them mundane. Flickering shots of flowers, babies and smiling people are cut with pieces of Mekas’ verse: “the beauty of the moment overtook him & he did not remember anything that preceded that moment.”

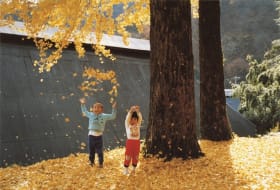

Tazuko Masuyama, 1982. Collection of museum in honor of Tazuko Masuyama.

“Camera-Obasan” Immortalizes a Dying Town

Also featured in Walls & Bridges is a photographer with a similar spontaneous approach. Tazuko Masuyama was from Gifu Prefecture’s Tokuyama Village, an area that is now underwater. She lost her husband in the war and she farmed and ran a guest house. She picked up a Konica film camera at age 60, when the Tokuyama Dam project, responsible eventually for the flooding of the village, was underway.

Her vast body of photos is the best documentation we have of the lost village. Creating a kind of town census, she documented every little corner of Tokuyama life: bon dances, children walking to school, people smiling in their workwear. Masuyama regarded the local environment with the same respect, tenderness and artistic appreciation she had towards her neighbors.

She was overwhelmed, too, by the prospective loss of plant life with the construction of the dam. The grief and love that went into these photos make you feel as if you are looking through old family albums.

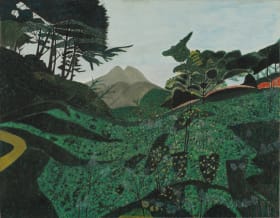

Katsushiki Higashi, Mt. Yufu Seen from Kawanishi, n.d. Yufuin Art Stock.

From Lumberjack to Painter

Katsushiki Higashi also appears to be a nature worshipper – and despite the (perhaps unintentional) tendency towards abstraction in his paintings, the desire to capture his surroundings with great lucidity is apparent.

Higashi worked as a lumberjack for many decades, ever since his mother died in his youth, in his native Hita, in Oita Prefecture. After entering a nursing home in Yufuin, he started painting the region’s landscapes fervently.

While you could attribute his style to a lack of pretension or exposure, his knack for describing foliage, snow, blossoms, water, etc., in bold blocks and flecks, with equally vibrant color choices, are uniquely refined. And while he was prolific and painted everyday, you sense his patient, quiet appreciation for reliving these views through watercolor.

Zbyněk Sekal, Masked Mask, 1990. Private collection. Photo: Oto Palán.

Kafka-esque Boxes

Likewise, the sculptures of Zbyněk Sekal, who was born in Prague and spent several years of his youth in concentration camps, could be self-reflective. A talented linguist, Sekal worked as a bookbinder, graphic designer and translator after narrowly escaping death during his imprisonment.

In the 1960s, he started making his “boxes,” convoluted structures made up of intersecting geometrical forms, that evoke the maze-like dystopias of his admired Kafka and, more generally, linguistic forms of communication. His works require you to walk around and peer inside them to appreciate their complexity and, interestingly, to confirm they are not 2D.

A Modern Renaissance

Adjacent to Sekal’s curious objects is the work of Silvia Minio-Paluello Yasuda. She married an aspiring Japanese sculptor in Paris, had kids and moved to Japan with her family. As a full-time mother, she worked on her art at night, producing a body of sketches, paintings and sculptures clearly informed by modernism, the Italian Renaissance and Japanese art.

The sketches (assembled by her husband), while shockingly contemporary, give you insight into her creative interests, like angels and Biblical scenes. The nearby sculpture of St. Catherine of Siena and her monumental “Portrait of a Family” are grave and epic enough to immediately grab your attention.

Silvia Minio-Paluello Yasuda, detail of St. Catherine of Siena and Rlief of Her Life, 1980-1984. Matsuyama City, Ehime. Photo: Sadamu Saito.

At Walls & Bridges, you are looking at a diverse collection of films, photographs, paintings, sculptures and drawings. Each room of the exhibition could very well be its own show. So what unites these artists, other than some level of struggle and great levels of imaginative force? By their passion for expression, they were all able to transform the inhibitory “walls” around them into “bridges” of creative opportunity. Further, they share an emphasis on memory – immortalizing life. The artists’ personal experiences and professional output are linked so closely, their works become means of autobiography or memoir.

Walls & Bridges – Touching the World, Living the World is on view at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art until October 9. See more here.

Feature image: Tazuko Masuyama. Collection of the museum in honor of Tazuko Masuyama.