If there’s one thing that can be said about Takashi Shimizu, it’s that he finds what works for him and he sticks to it. After the success of his Ju-On (The Grudge) movies and Howling Village, the Japanese horror director is back in 2021 with Suicide Forest Village (樹海村), described as a story about a village in Aokigahara that “holds a grudge.” Located at the foot of Mt. Fuji, Aokigahara is perhaps known better as Japan’s infamous suicide forest where a lot of Japanese people tragically choose to end their lives.

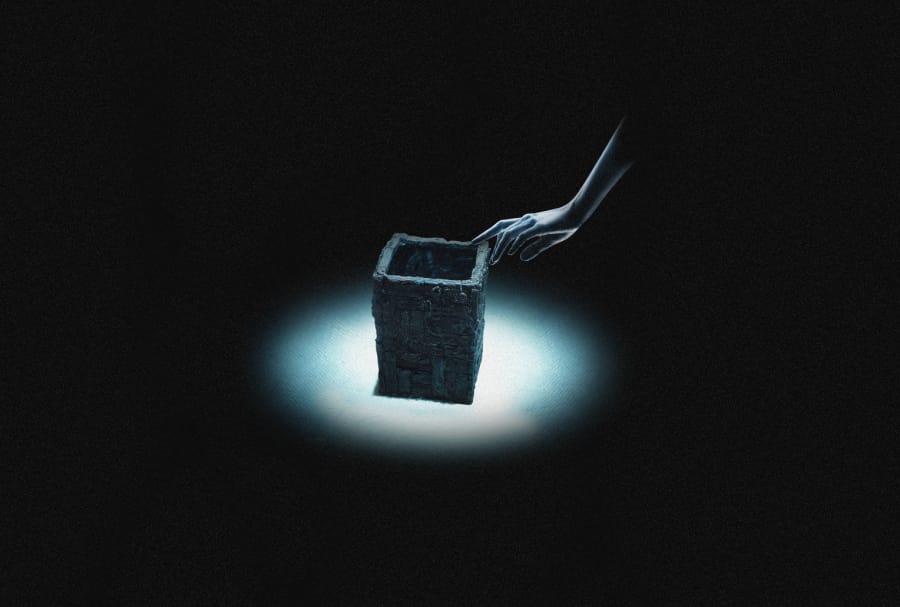

Plenty of legends and horror movies for that matter exist about it, but in his new film, which premiered on February 5, 2021, Shimizu tries to make the story his own with an inclusion of a cursed wooden box that acts as a portal to a world of death. The end result probably won’t become as iconic as the ghostly Kayako from The Grudge but the movie is still interesting and worth examining because it deftly lays out the most common features of Japanese horror movies.

The Supernatural Terror of Nature

Japanese scary stories can most likely trace their lineage back to tales about yokai – paranormal creatures that are almost always part of the world of nature by either living in forests, exhibiting animal characteristics, or literally being magical animals like the tanuki raccoon dog. This seems to inform modern Japanese horror where the source of the stories’ malevolent forces is very often rooted directly in nature, for example, in Kwaidan (1965), where one of the stories centers around snow. In Suicide Forest Village, the link is obvious, what with the horror literally coming from a wooden box connected to a forest of the dead.

An interesting thing to note about the supernatural force of nature found in Japanese horror is that it’s basically unstoppable. It’s primordial and immortal, which is why you can’t really escape from it. In Western horror, evil or danger can be fought, often with a shotgun to the face. In Japanese horror, though, there’s not really much you can do once the supernatural sets its eyes on you. The best you can hope for is that it simply never notices you in the first place. This is explored wonderfully in games like Silent Hill, where brute force can briefly hold the horror at bay, but it will never defeat it, because Japanese horror loves to remind us that we humans are small and powerless in the face of a big scary world that we can never fully understand or conquer.

An interesting thing to note about the supernatural force of nature found in Japanese horror is that it’s basically unstoppable. It’s primordial and immortal, which is why you can’t really escape from it. In Western horror, evil or danger can be fought, often with a shotgun to the face. In Japanese horror, though, there’s not really much you can do once the supernatural sets its eyes on you. The best you can hope for is that it simply never notices you in the first place. This is explored wonderfully in games like Silent Hill, where brute force can briefly hold the horror at bay, but it will never defeat it, because Japanese horror loves to remind us that we humans are small and powerless in the face of a big scary world that we can never fully understand or conquer.

What this usually means in practice is that, in Japanese horror, you don’t have to go make out in the basement of an abandoned mental hospital or buy obviously cursed dolls to meet with a terrible fate. Nature is all around us in some shape or form, and we can fall victim to it at any time. But this malicious force seems to strike more often when a character is lulled into a false sense of security by modernity and technology.

Technology Won’t Help and Will Harm

A big part of Japanese horror is the message that for all of humanity’s technological and societal progress, none of us are safe. That’s why in The Grudge, the plot is centered specifically around a haunted suburban home, a symbol of prosperity and stability. More often, though, this theme is explored by technology itself being a catalyst for horror. In Suicide Forest Village, this is achieved by one of the characters being part of an online group interested in the occult. In The Ring (1998), the technological horror catalyst is a VHS tape, very modern technology when the story first came out. In One Missed Call (2003), it’s cellphones and voicemail.

This is something that could only really be born in a country as famously safe as Japan. Their horror tries to destroy the audience’s feelings of security by corrupting things like technology (the symbol of progress that creates their safety) or things that represent the cohesion of social order. That’s why The Grudge is a story about a dark, twisted version of a suburban Japanese family. The story in Suicide Forest Village, on the other hand, ultimately goes back to the issue of caring for the infirm and the elderly, a foundation of modern Japanese society. In the movie, it’s turned on its head, revealing disturbing truths about the darkness of the human soul that prove that society and civilization are ultimately a sham. They’re giants standing on feet of clay and wobbly stilts, and it’s just a matter of time before they all come crashing down.

That’s why so few Japanese horrors have a happy ending. Because the real monsters are ultimately the vicious, cruel nature of humanity and the cold, uncaring, unstoppable fabric of reality. And how are you supposed to fight those?