A fresh-faced GI from a small town in America, Robert Whiting knew little of Japan’s capital before arriving on these shores just under 60 years ago. The then 19-year-old soon fell in love with a place he says, “evolved, in a few short years, from a fetid, disease-ridden third-world backwater into a modern megalopolis in what many believe to be the greatest urban transformation in history.”

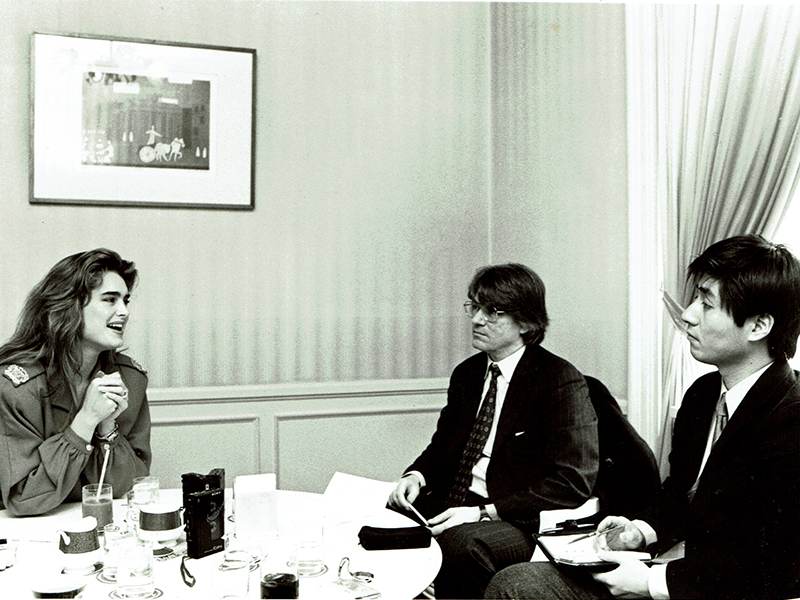

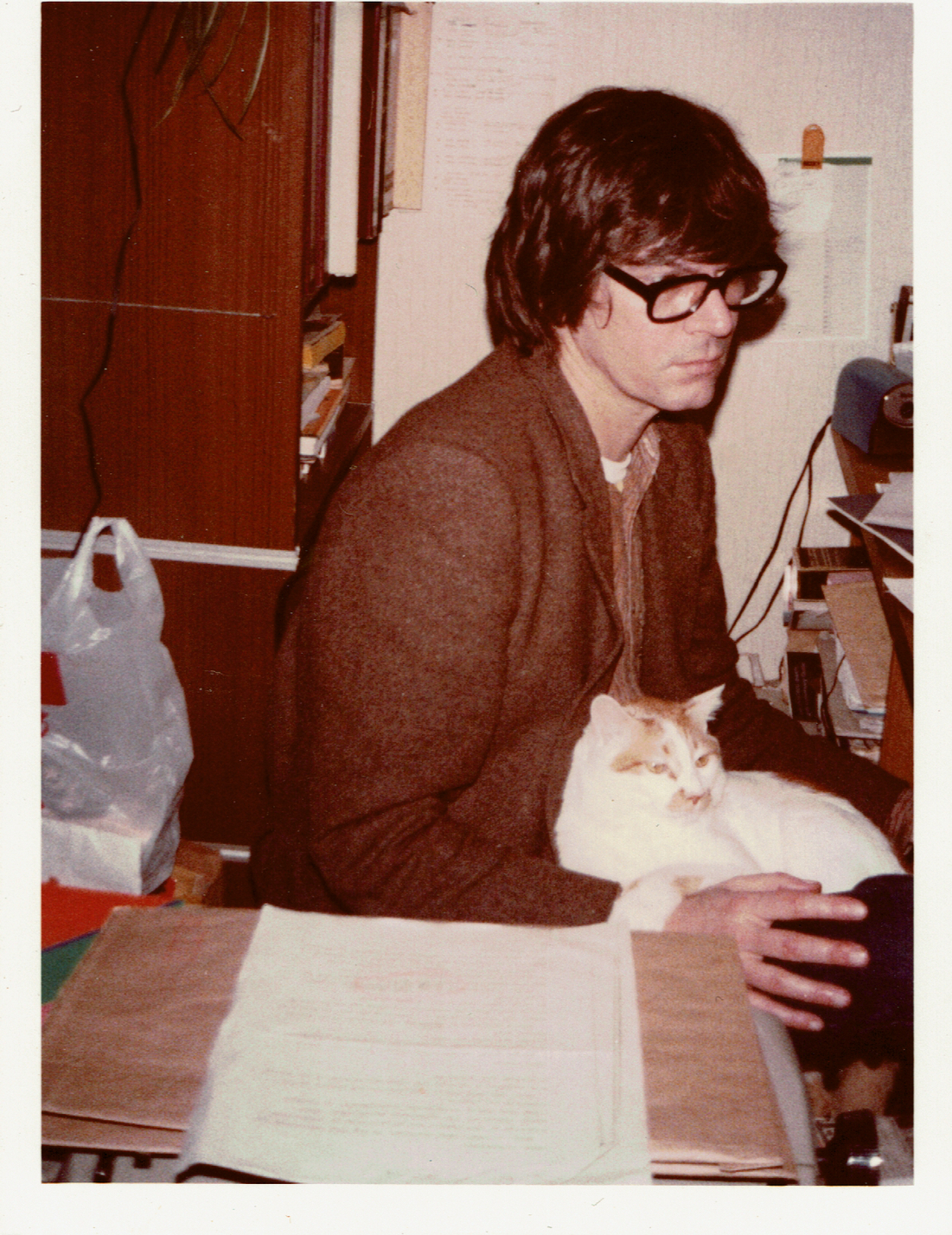

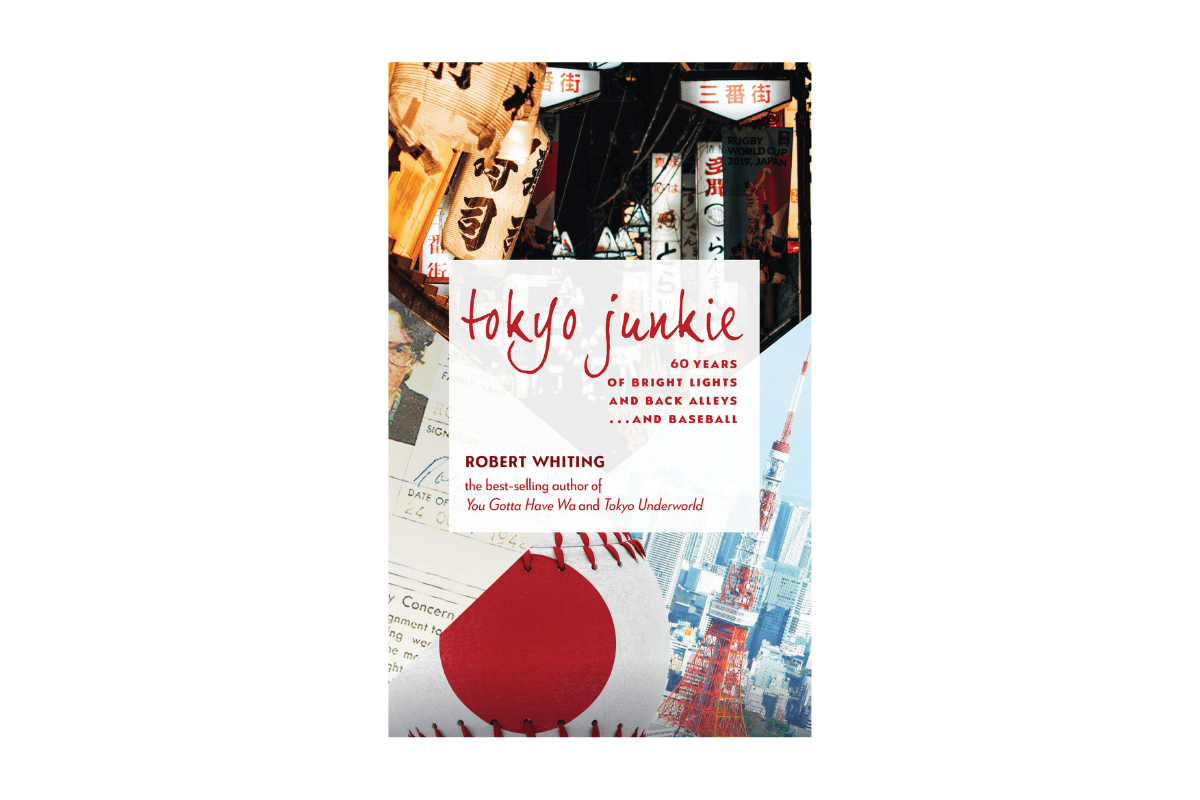

These words come from Whiting’s latest book, Tokyo Junkie, which unlike his previous publications such as You Gotta Have Wa and Tokyo Underworld, is a very personal account, detailing his relationship with Tokyo and how they’ve both grown over the past six decades. TW recently sat down with the revered author to find out more.

What were your first impressions of Tokyo?

My first weekend in the city was mind-blowing. The sea of people, crowded trains, platform pushers – I’d never experienced anything like it. The energy of the place sucks you in. Walking down the streets of Shinjuku with the neon signs was hypnotic.

How would you describe the buildup to the 1964 Olympics?

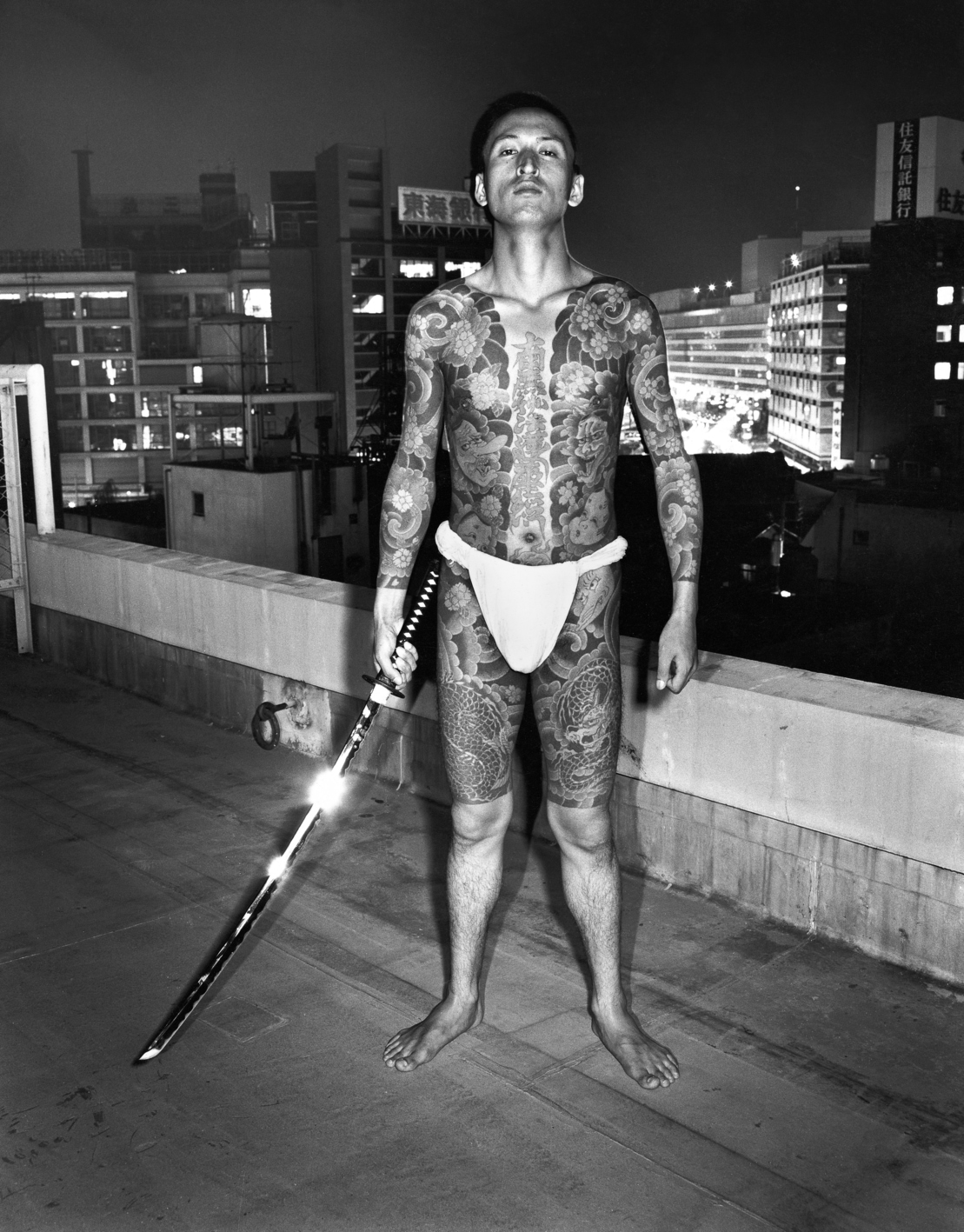

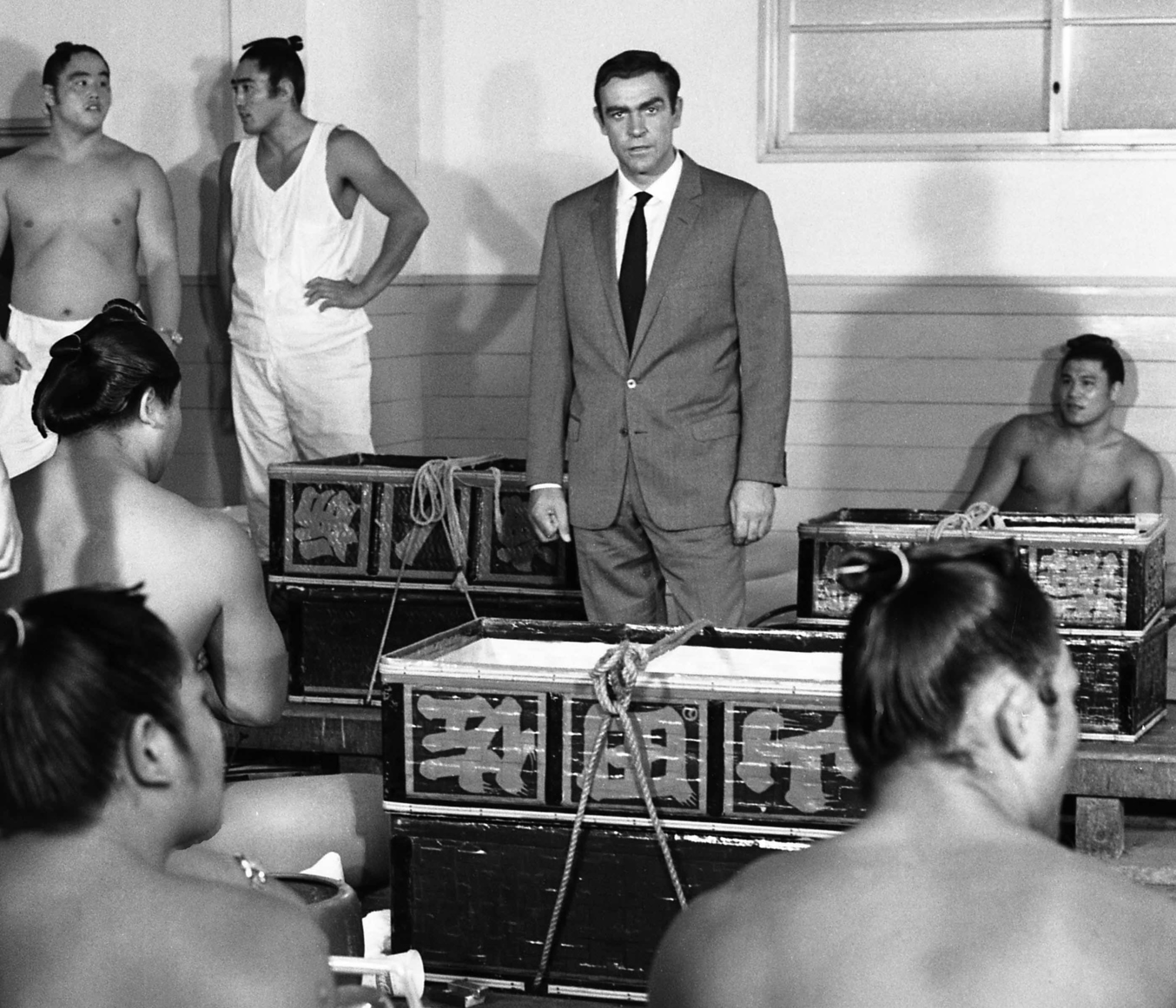

When Tokyo got the Games in 1958 it had one five-star hotel falling into disrepair, no highway system, no basic infrastructure, high infant mortality rate, few English speakers and undrinkable water. The attitude was, how the hell are they going to do it? When I arrived, it was like one gigantic construction site. From a swamp backwater nobody wanted to visit to a high-tech megalopolis used for a James Bond film, the transformation in such a short time was remarkable.

What are your memories of the Games?

I remember the tears in Japanese people’s eyes during the opening ceremony. This was their entry back into the world after the defeat in the war. There were many standout moments such as Valeriy Brumel’s high jump gold and Bob Hayes in the 100 meters and relay. I decided not to include them in the book as they weren’t related to the main theme. Instead, I focused on three events involving Japanese athletes.

Why were they so significant?

Kokichi Tsuburaya’s story is a tragic one. He was caught by Britain’s Basil Heatley in the marathon (won by Ethiopia’s Abebe Bikila) and ended with a bronze. He thought he’d let everyone down and never got over that, committing suicide in 1968. In judo Japan won the lower categories but the open weight was the main event. Akio Kaminaga was expected to win yet was pinned by Anton Geesink. The Dutchman stopped his coaches from celebrating as it would’ve been a breach of etiquette. The Japanese people respected him for that but were so disappointed. It was left to the women’s volleyball team to save the Olympics.

The Oriental Witches?

Yes. The final night of the Games and 95 percent of the TV audience watched (still a record) them take on a bigger and stronger Soviet Union. The people were riveted. Everything stopped for that final point. Those ladies practiced 10 to 11 hours daily. Their victory restored national prestige and showed that fighting spirit could overcome superior strength, weight and height.

Purchase Tokyo Junkie here or visit your local bookstore.

Photos courtesy of Robert Whiting