Time doesn’t simply flow; it warps weirdly. This is one of the many things that we agree on when Anne Murayama comes to the Tokyo Weekender office to chat. She’s specifically referring to the pandemic and how it changed our perception of time, but we also talk about timing as she’s just come back from an extended hiatus. After stopping all communication with the world for more than a year, the photographer, known for capturing her surroundings in black and white, resurfaced online in June 2023, published a new photo zine in July and sat down for an interview with us in August.

self portrait

Life in Color, Feelings in Monochrome

“Murayama” is the family name of the photographer’s husband and a name she has embraced. Previously, she worked under the artist pseudonym Erin Cross in her hometown of Manila, the Philippines, as a successful photographer and the editor-in-chief of Lomography’s online magazine.

Like many artists, Murayama’s path to a creative field was a winding road. Though she was taking photos with film cameras in her college days, she was training to be a medical professional, even completing two pre-med degrees before giving in to the sinking feeling that working in a hospital was not for her.

“My family wasn’t happy with my decision,” she tells me. “But after doing my best to love science, my heart was in the arts after all. It wasn’t easy, but I’m happy to have followed my gut.”

Between Manila and her permanent move to Tokyo, she’s started too many publications, projects, photo books and exhibitions to recount here. Her works have been exhibited, featured and published in Cambodia, Italy, Japan, the Philippines, Singapore, Spain, the U.S. and the U.K. An impressive collection of cinematic monochrome photos and her own words confirm she’s a fan of black-and-white films by the likes of Alfred Hitchcock and Jim Jarmusch.

However, she didn’t always take only black-and-white photos. That practice began in 2013 when she first visited Tokyo.

“A dream come true,” she says, then clarifies that it was heartbreak that triggered the change. She recounts her move to monochrome in an old blog post on Medium: “I felt like my black-and-white pictures heightened my real emotions at the time — dark and morose. Soon, I found myself buying disposable Ilford film cameras in Shinjuku.”

Black-and-white photography has become profoundly significant for Murayama in the decade since.

“I think that black-and-white photography provides a room for appreciating timeless beauty,” she explains. And in her artist statement, she writes, “To me, black-and-white images illuminate an evocative kind of solitude that I find fascinating — like a phantasm: stripped off of hues, but not devoid of spirit.”

Mono as in One

About that aforementioned solitude — it stains all of Murayama’s photos, like it pervades the lives of people. The back of a hurried woman on the subway station stairs; a lone man with a sign saying, “Will you marry me?”; a window with a single mannequin in it. In a gargantuan city of millions like Tokyo, it shouldn’t be that easy to capture scenes with solitary figures in them.

“The older I get, the more I realize how sadness is innate in all of us,” Murayama says. “This is the reason I try to capture those scenes amid Tokyo’s hustle and bustle.”

Murayama’s photos are also often suspended in blurry movement, and that, too, is an artistic choice.

“I let my photographs be driven by motion and emotions instead of being cautious of composition. Most of my pictures are blurred, coarse and out of focus (an homage to the Japanese are-bure-bokeh aesthetic). All the grit and grain represent the rawness and roughness of real life,” she explains.

In her experimental photography series “MonoWalk,” which she started spontaneously during the pandemic, Murayama livestreams on Instagram while walking. She lets her viewers be her shutter as they take screenshots of photo-worthy moments. It’s simultaneously a loss of control and freedom from constant decision-making. It’s also a project that has found a fragile balance between solitude and connection, between collaboration and creation — but without the burden of commitment.

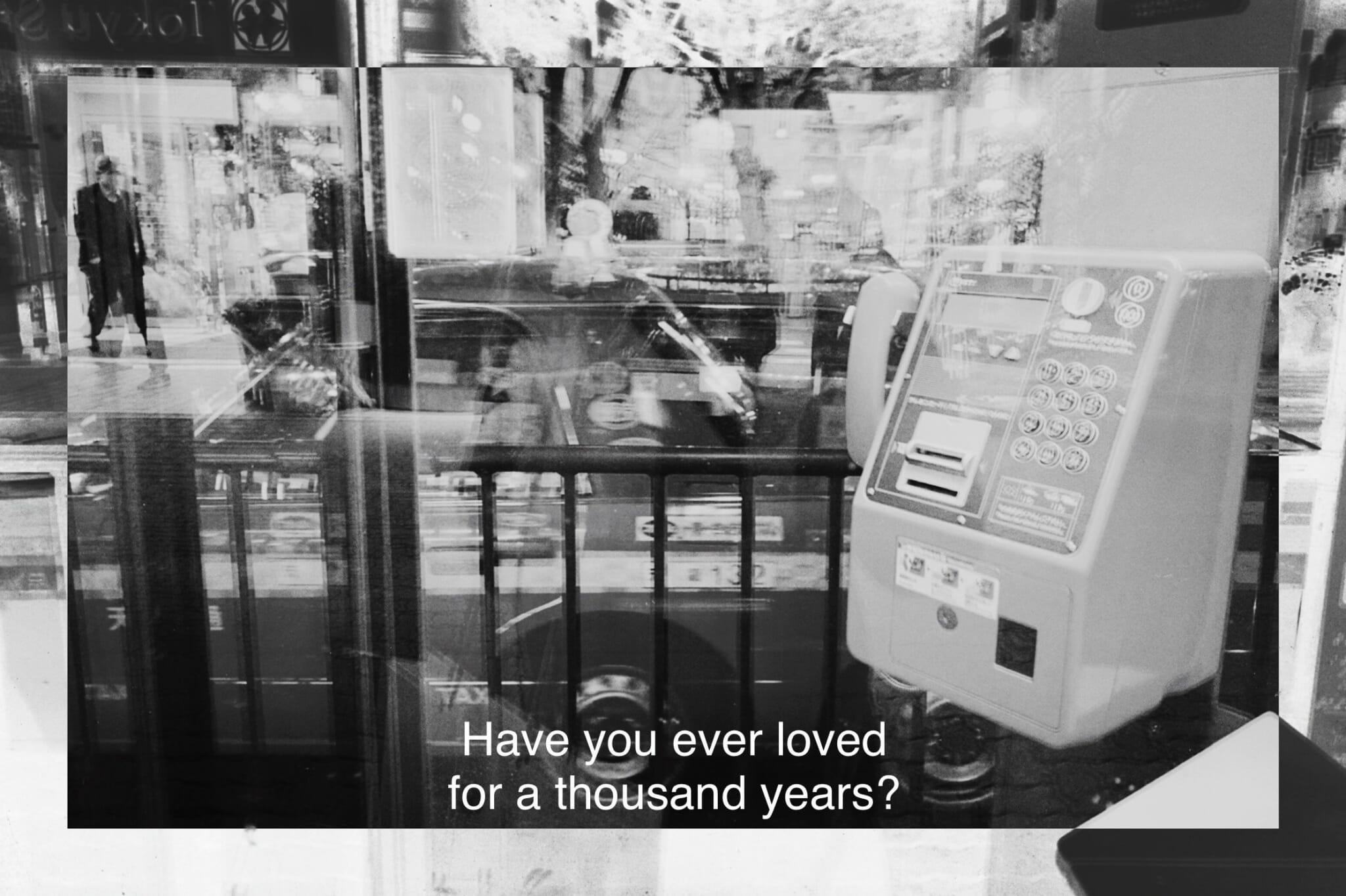

I soon realize many of Murayama’s seemingly individual projects have a community undercurrent. In her “Subtle Titles” series, she adds subtitles to photos in a bid to simulate film stills.

“I ask my followers to anonymously submit thoughts and feelings,” the photographer reveals, then adds, “The more personal it gets, the more universal it becomes.”

Now. Here. Ephemere.

At times subtly, but increasingly more deliberately, Murayama is trying to create a community. Aside from her collaborative projects, zines and group exhibitions, she also founded the Japan chapter of the street photography collective Women in Street in 2020.

“The streets are for everyone to taste, and I’m in search of all the flavors, scents and sounds,” she says. “I find comfort in roaming the streets, familiar and strange alike, as I always see a different grit, a different light.”

Murayama goes on to explain that although Japan is photogenic and safe, which are the perfect elements for a good street photography scene, women photographers tend to be more timid and shoot from afar. For now, the Women in Street Japan group is still in its infancy, and Murayama expresses the need to have more people join her to help lead it.

In the meantime, she’s putting all her energy into Ephemere (stylized as ephemere.), a small gallery space above an izakaya just two minutes on foot from JR Musashi-Koganei Station. Ephemere is slated to open with a group exhibition of black-and-white photos on October 1.

“As a foreigner in Japan, I also know how intimidating it can be to participate in photography events here because of the language barrier,” Murayama shares. “To have a sense of belonging is so important. Especially to us foreigners.”

Ephemere is also the brand under which all of Murayama’s future publications will be released. She has now restructured them into three groups: “Anatomy,” a series of photo zines featuring her work; “Anarchy,” for collections of the works of others; and “Anagrams,” for showcasing a single photographer’s works. In addition to these, Ephemere is open to collaborations with other curators and publishers.

Murayama is still very private about the personal tragedies and illnesses that befell her during the pandemic. However, we don’t need all the details to see how her struggle and survival have strengthened her dedication to helping others in this short, fleeting, ephemeral life.

“As I tread through what I believe is my second life, I try to live it more meaningfully. I have so much to share, stories that I think could, maybe, help other people,” she says. “So, I have been working on my autobiography. I hope I can tell my whole story someday.”

Find Anne Murayama and her work on Instagram.

This article was originally published in the TW September-October 2023 issue

Updated On October 2, 2023