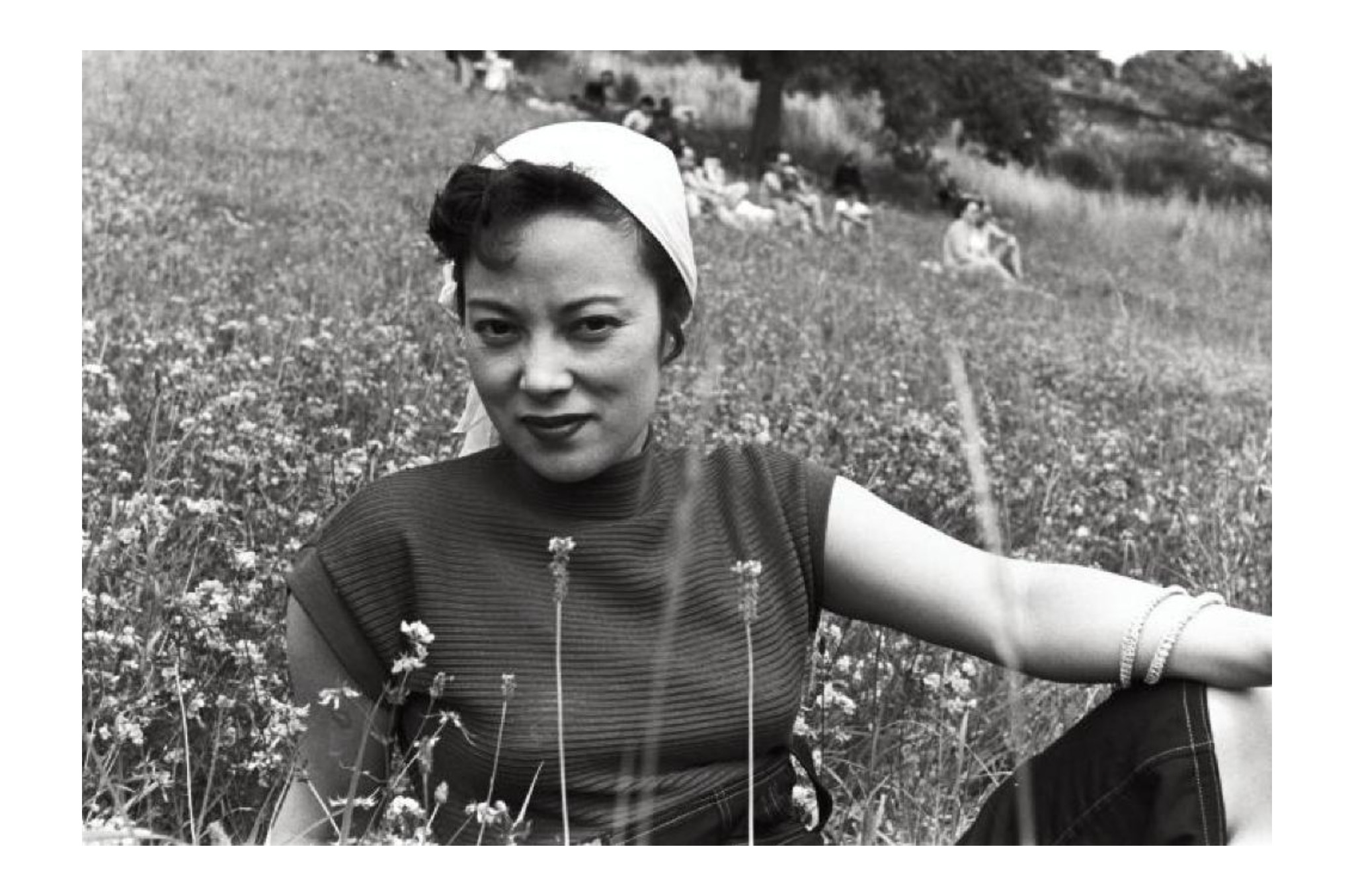

She was one of the most popular singers in all of China and Japan. A friend of Charlie Chaplin, she was also a well-known actress, appearing in a number of Akira Kurosawa movies. On top of all that, she was also a trailblazing politician who advocated for Palestinian rights over 50 years ago and a self-taught polyglot. Any one of these would make for an impressive lifetime achievement. But when fate asked Yoshiko Yamaguchi which legacy she wanted to go with, she refused to choose and picked all of the above.

As we approach September 7 and the 10th anniversary of her death, let’s remember one of the most fascinating women in modern history.

© 20th Century Fox Film Corp

What’s in a Name? Quite a Lot, It Turns Out

Born in 1920 to Japanese settlers in Manchuria, China, Yamaguchi spoke Japanese as her first language while picking up Mandarin and later even a little Russian after befriending one Lyuba Monosova Gurinets at her school. Yoshiko’s increasingly international upbringing was later supplemented by singing lessons from an Italian soprano. Through these experiences, the young girl unknowingly laid down the foundation for her future, turbulent life.

After Japan’s invasion of the region in 1931, Yamaguchi’s singing got her scouted by Man’ei, the Manchukuo Film Association, who, interestingly, would later give the world Japan’s first female director. Because she was fluent in Mandarin by then, Man’ei wanted Yamaguchi to use a name given to her by her Chinese godfathers: Li Xianglan — also spelled Li Hsiang-lan or Ri Koran in Japanese — and pretend that she was Chinese in a series of romance movies.

These films actually turned out to be propaganda pieces about Chinese women falling in love with Japanese soldiers or sailors and so on. In one infamous instant, her character got slapped in China Nights (1940) after which she apologized and exclaimed, “It didn’t hurt at all to be hit by you. I was happy, happy.”

Perhaps because of her young age and a naive belief she was helping the people of Manchuria, whom she considered friends and family, Yamaguchi didn’t fully realize the purpose of her work. “I thought my films were simple romances,” she later told The Boston Globe in 1991. Immediately after the war, though, she publicly apologized for her role in Man’ei’s propaganda films and decried the invasion of Manchuria. This was a very risky move for an entertainer.

Ri Koran or Xianglan?

One of the least controversial (at least in Asia) of her movies was Eternity (1943), a joint Japanese-Chinese production shot in Shanghai in which the two countries worked together, united by their shared hatred of the British. An overt critique of the Opium War, the film became a hit thanks to its catchy songs. Many are still considered Chinese pop classics and, at the time, made Xianglan one of the most popular singers in all of China.

She was equally popular as Ri Koran in Japan, where her performances always attracted crowds of people. Yet as she wrote in Fragrant Orchid: The Story of My Early Life (published in 1987), she struggled with her dual identity.

During a Beijing press conference held shortly after the premiere of Eternity, she was questioned by a journalist about her roles in Man’ei propaganda films and was finally asked: “Where is your pride as a Chinese?” She wrote that she almost broke down and disclosed her Japanese heritage but ultimately restrained herself.

In Japan, meanwhile, they thought she was acting, talking and dressing a little too Chinese for their liking. In her mind, things weren’t so clear-cut. She saw herself as a person of two nations, with China being her “home country” (or “fatherland” in some translations) and Japan her “ancestral country” (or “motherland”). Unfortunately, one incident would eventually force her to declare herself for one country or risk death.

SCANDAL (1950), Akira Kurasawa. © Shochiku Co., Ltd. c/o The Japan Society

A Geisha Doll to the Rescue

After World War II, Xianglan was arrested in Shanghai and sentenced to death by firing squad for “collaborating” with Japanese imperial forces as a Chinese citizen. Her parents thankfully managed to find her Japanese birth certificate but due to travel restrictions, it had to be smuggled into Shanghai inside the head of a geisha doll with help from Xianglan’s old friend Gurinets.

While this move spared her life, it also ended her career in mainland China, with one judge calling the young woman “a Chinese impostor who used her outstanding beauty to make films that humiliated China and compromised Chinese dignity.” In 1946, Xianglan went on hiatus as Yoshiko Yamaguchi and relocated to Japan to continue her acting career.

A World Tour

Working off the fame of Ri Koran, Yamaguchi quickly found work with Kurosawa, first appearing in Escape at Dawn in 1950, for which he wrote the screenplay. That same year, she starred in Scandal opposite screen legend Toshiro Mifune, this time directed by Kurosawa himself. Yamaguchi then looked for a new challenge, eventually moving to the United States, where she adopted yet another name. This time she called herself Shirley.

Shirley Yamaguchi appeared in a few movies and one Broadway musical using the English skills she perfected in Shanghai. It was during this time that she befriended Chaplin while working on the soundtrack for Limelight (1952). Sadly, her association with Chaplin led to her being barred from the country as the famous actor was forced to leave the States following an FBI anti-Communist investigation.

Slowly running out of countries, Yamaguchi briefly resurrected the name Xianglan and appeared in a few Chinese-language movies shot in British-controlled Hong Kong. By 1958, though, she got acting out of her system, and Li Xianglan and Yoshiko Yamaguchi were both put to rest, only to be replaced by Yoshiko Otaka, the new wife of the Japanese diplomat Hiroshi Otaka, whose work took the couple to Sri Lanka and Myanmar.

© The Isamu Noguchi Photographic Archive

Never At Rest

Upon their return to Japan, Yoshiko Otaka entered the world of journalism, working her way up to the position of a news anchor for Fuji TV in 1969, where she reported on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, advocating for Palestinian rights.

Five years later, she pivoted yet again, this time to the world of politics. In 1974, she was elected to the House of Councilors, where she served for 18 years. She spent the rest of her life championing women’s rights around the world before passing away at age 94.