Osamu Tezuka, author of such culture-defining works such as Black Jack, Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion, has more than earned his title of “Father of Manga.” But what about the medium’s grandfather and other ancestors? Well, the term “manga,” which loosely translates to “whimsical pictures,” was popularized by Hokusai Manga, a collection of sketches by Katsushika Hokusai, one of the greatest artists in Japanese history.

The comic book format of paintings accompanied by text to tell a coherent story had been pioneered earlier by mid-18th century kibyoshi (“yellow covers”) like Edo Umare Uwaki no Kabayaki by Santo Kyoden. But go back further in time and you eventually come across Japan’s potentially-first manga and, following that, the person who started it all, right? Unfortunately, it’s a bit more complicated.

Panel from the first scroll of Choju-jinbutsu-giga, a monkey thief runs from animals with long sticks.

The Bishop of Toba and His Frolicking Animals

The person often credited as possibly Japan’s first mangaka is Toba Sojo, but that isn’t his real name. His monk name was Kakuyu, but because he came to prominence while holding the rank of “sojo” (roughly equivalent to a bishop in Japanese Buddhism) and living in a temple in Toba, Kyoto, he is usually called Toba Sojo by both Japanese and Western sources. Besides trying to achieve enlightenment and ascend beyond this mortal plane of desire and suffering, the priest’s other hobby allegedly included inventing manga in the form of paintings of animals acting silly.

Choju-jinbutsu-giga (“Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans”) is a set of four emakimono picture scrolls entrusted to the Kyoto National Museum and the Tokyo National Museum. The first scroll depicts anthropomorphic rabbits, monkeys, foxes and frogs bathing, wrestling and participating in religious ceremonies, which has been interpreted as satirical skewering of the Buddhist clergy by someone blowing off steam in a humorous style that we can still understand nearly a millennium later. The problem is that we aren’t totally sure that the person behind it was Toba Sojo… or that Choju-jinbutsu-giga even qualifies as manga.

The Difference Between Cartoons and Manga

The later scrolls depict animals in less frolicking moods, completely taking any satirical sting from the works like the frog Buddha of the first emakimono. That and the change in style between the scrolls and no accompanying text to help us out, makes it unlikely that Choju-jinbutsu-giga is the work of one author. And even if Toba Sojo was behind the first comical scroll, wouldn’t that make it more of a political cartoon rather than manga? Not necessarily.

The first scroll depicts dynamic movement. There might not be any modern-style panels containing the drawings, but there is a clear progression of scenes as the emakimono is slowly unrolled and followed from right to left, like in modern manga. Also, if we broadly define “manga” as a work of Japanese comic-book art, then Choju-jinbutsu-giga has a solid claim to that title because it’s one of the earliest examples of a native style beginning to crystalize in Japan.

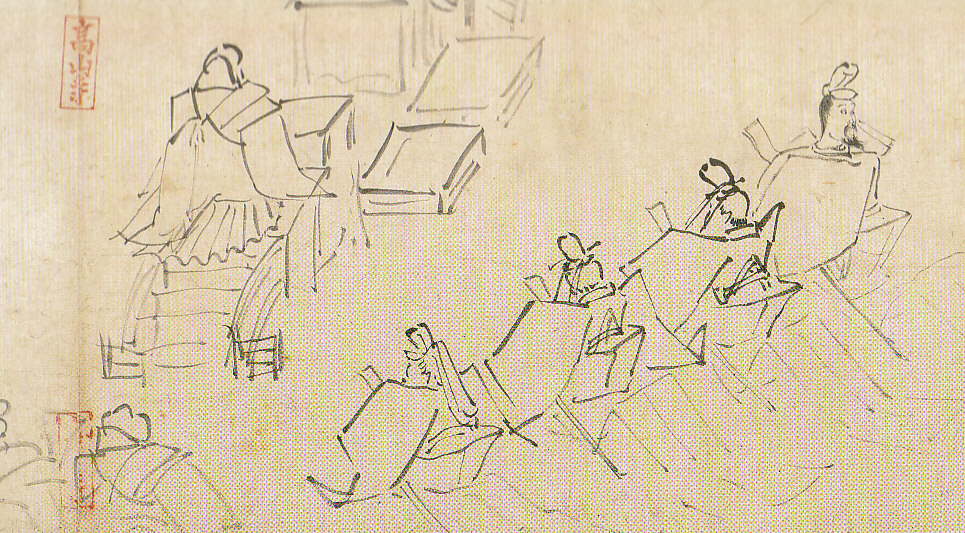

Panel from the fourth scroll of Choju-jinbutsu-giga, noblemen attending a Buddhist ceremony with a monk performing (left). | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Emakimono were very popular with the aristocracy of the Heian period (794–1185), when Chinese culture was synonymous with elegance, sophistication and everything good in art. You can see that in the vividly and richly illustrated 12th-century scrolls depicting the events from The Tale of Genji in an Asian “expressionist” style common in Chinese paintings of the time. The frolicking animals are different.

The illustrations are simple ink drawings on a white background. This was most likely influenced by the unpretentious art style of Japan’s emerging samurai class, which, as a bonus, also greatly resembles modern manga that still relies heavily on visual humor and simple black lines, especially with comedy titles.

Manga or Not, It’s Still Worth Our Attention

The Yomiuri Shimbun staff writer Kanta Ishida does not agree that Choju-jinbutsu-giga is the first manga. Using research about similar scrolls by Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata found in his book, Twelfth-Century Animation: The Elements Seen in the National Treasure Scrolls that Evolved into Movies and Anime, Ishida presents a simple conclusion: “There is no connection between the traditions of [Choju-jinbutsu-giga] and contemporary manga, including the domestic works we are familiar with in our daily lives and the foreign works that have increased with the growing number of manga fans worldwide.”

Besides, there is a (possibly) earlier work, Shigisan Engi Emaki, that also depicts dynamic movement and the beginnings of a native Japanese art style, so even if we really stretch the definition of “manga,” Choju-jinbutsu-giga might not be where it all began. But even if that’s the case, there is still enough to admire about the first scroll, from its use of humor that transcends time to conveying a lot of emotions and movements with the simplest tools and techniques. We don’t know exactly whom we have to thank for that, or if the work actually contributed to the development of manga, but in the absence of any other candidates and the gesture not hurting anyone, let’s just say: Thank you, Toba Sojo.