Often referred to as Japan’s Golden Age, the Showa era technically spans the entire reign of Emperor Hirohito, from 1926 to 1989. As it lasted for most of the 20th century, it encompassed the identity of a whole generation. Showa saw the lead up to WWII, the starvation and poverty during the war, and the dramatic economic growth in Japan’s post-war period. It is usually this intensive period – between the 1950s and 1970s (Showa 30s and 40s) – that the Showa revival reflects.

Though Japan faced many hardships during this time, it also experienced a burst of technological advancement and opportunities. With this came prosperity, and then excessive materialism-led happiness – especially through modern luxuries that made daily life more convenient. This tenet to work hard and buy many things has endured even after the bubble burst in the late 1980s. It is no surprise, perhaps, that after the experience of long, severe poverty and a ban on many things Western, that Japan adopted so much so freely, albeit with their own interpretation.

The Showa Era Renaissance

Over the last decade or so, there has been a steady growth in interest in the Showa period. Once thought of as dasai (tacky) and shunned by modern youth, the era has found its own in a time where retro chic is cool. This wave of nostalgia has permeated every aspect of modern culture from fashion, to media, and even travel.

Showa period-based popular culture made its way back into mainstream media in the mid-Noughties: among many romanticized TV dramas and films, the 2005 movie Always: Sunset on Third Street (see trailer below) was a huge hit, and its 2007 sequel was equally well received. Last year’s NHK morning drama, Toto Nee Chan (alternative title Fatherly Sister), hit home with many as it captured the feeling of possibility and the drive for people (especially women) to be and do more.

Businesses have capitalized on this interest in nostalgia with retro Showa 30s theme parks in Odaiba and Shibamata, and Showa-styled sweet shops in Ikebukuro and Yokohama. Regional areas like Atami and Ome have benefited from promoting their retained Showa-ness, and even taishu sakaba – blue collar drinking places for the masses – have been experiencing an upturn in business. Vintage fashion, including kimono, has seen a rise in popularity among those in their 20s. All these cultural and physical aspects are enjoying a Showa retro boom, but the question remains: why?

Where Did the Retro Revival Come From?

There is a lot of speculation on why this wave of wistful yearning for the past holds on so strong, but there are a couple of factors that seem to be prominent. Rie Tanaka*, an employee within the Tokyo tourism industry, explains that during the post-war period, and pretty much ever since, Japanese people have looked towards the latest new thing, and forgot about or simply have not been interested in the recent past.

With current economic stagnation, however, young people now look inward and backward: they save money by traveling domestically instead of internationally, and are learning to appreciate what came before them. In parallel, an interest in Japan’s history – and increasingly not just the Showa period – seems to have increased in her field. “Because many Japanese millennials only see hardship in their future, it’s no wonder they look to the past. They see a time that still had a bright and hopeful future.”

Interestingly, Hosei University professor and specialist in social psychology Tatsuo Inamasu predicted this retro revival would be different from other fads. In a 2006 article in Japan Economic Forum’s Japan Spotlight, he said the reason for this is because the generation who lived it – the dankai sedai (“baby boomers”) – are not only still alive and well, but are actively promoting its appeal themselves. As many of that generation have retired and volunteer in their local communities, they are able and willing to meet the demand for a glimpse of Japan’s good ol’ days.

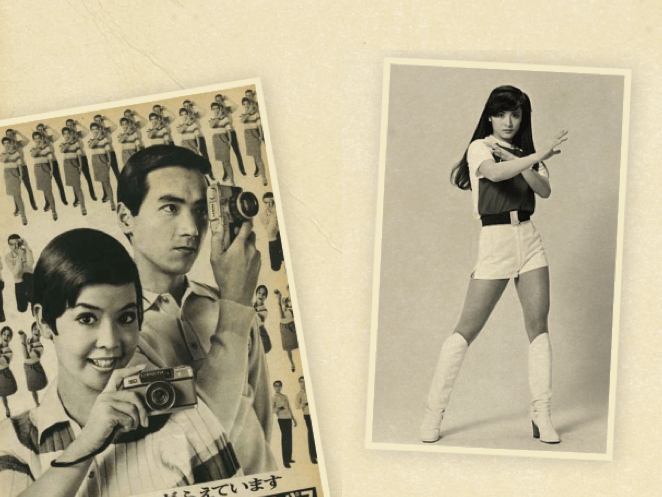

The streets of Ome city still boast Showa-era movie posters

Show-a, What Now?

There is no doubt that Showa-era items and places are sought out by both native Japanese and non-natives alike, whether it is for the period’s old world charm or its avant-garde design. It has yet to been seen if the revival will continue to thrive, but perhaps there is an advantage in considering the past for inspiration. Japan may have lost something in its rush to consumerism, and now both younger and older generations are trying to get that back. If that search includes taking off the rose-tinted glasses once in a while, the embrace of a slower charm from a bygone era may just be what this hyper, sped up, stressed out everyday needs.

*Name has been changed

Wada tobacco shop in Atami

Where to Find That Showa Feeling

While you can find little bursts of post-war atmosphere in Tokyo’s shotengai, kissaten coffee houses and yokocho, to really submerge yourself in the Showa experience we recommend these spots:

Ome: The city of Ome in western Tokyo actively promotes its Showa-ness, and visitors will find original movie signs posted all over, as well as old-style shopping streets and even a Showa Retro Packaging museum.

Atami: Once touted as the French Riviera of Japan, Atami fell out of favor after the bubble burst. Several restaurants still serve original recipes of Japan’s first take on Western cuisine (omurice, tonkatsu, spaghetti Napolitan) and many shops retain their original decor. Others, previously shuttered away, have been renewed.

Ota Ward: Famous for having the largest number of sento of any ward in Tokyo, Ota is home to many well preserved traditional houses (one of which has been turned into the Showa Lifestyle Museum) and shops. You may even catch someone grilling senbei (rice crackers) on the sidewalk.

Ikaho Toy, Doll & Car Museum: Ikaho in Gunma is famous for its rustic onsen resort, but is also home to a delightful toy museum that doubles as a classic car museum, and a tribute to Showa idol posters.

Kirakira Tachibana Shotengai: Old shops galore line this street in Kyojima, Sumida ward, selling oden, nori and more. There are monthly morning markets on the fourth Sunday of each month for an extra local feel.

Tire Ichiba Sagamihara: Although this shop’s main business is selling tires and hubcaps, it’s almost equally famous for its old-school vending machines selling popcorn, cup noodles, soba, udon and even hamburgers.

National Showa Memorial Museum: The Showa museum national facility collects, preserves and exhibits everything related to Japanese citizens’ lives during and after the Second World War.

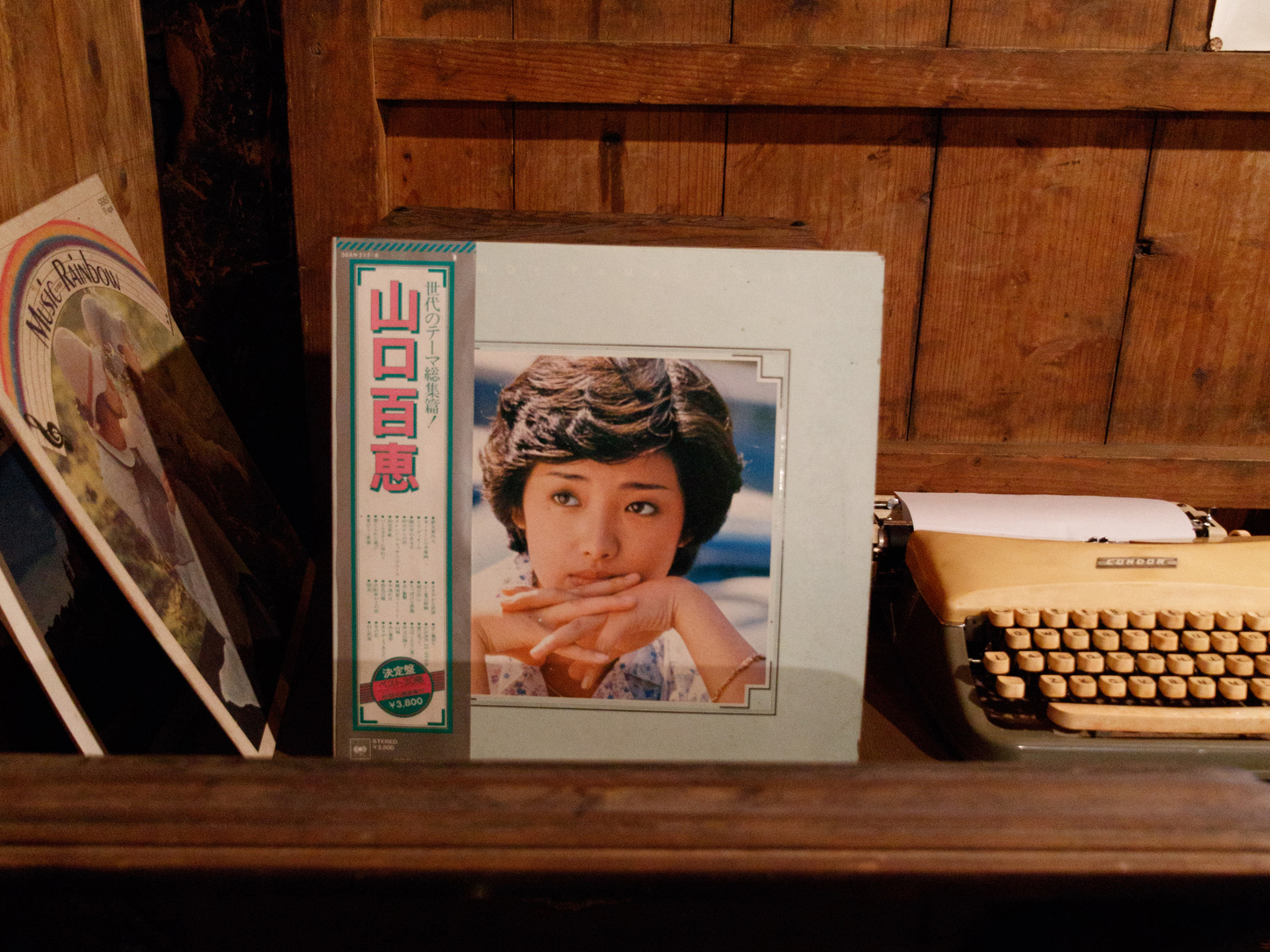

Momoe Yamaguchi, one of Japan’s most popular singers during the 70s

Parties and Markets for Showa Hunters

Junk Show: A semi-regular treasure trove of pre-loved toys, homeware and accessories.

Showa Retro Ichi Market: A biannual event where original Showa period furniture, accessories, and more are on sale.

Related Articles

- Jazz Records and English Breakfast: Donato Kissaten

- Japan Back Then: The Stories That Gripped the Nation in the 1950s

- Japan’s Artisan-Made Vinyl Toys Are Making Collectors Go Wild

Updated On January 24, 2024