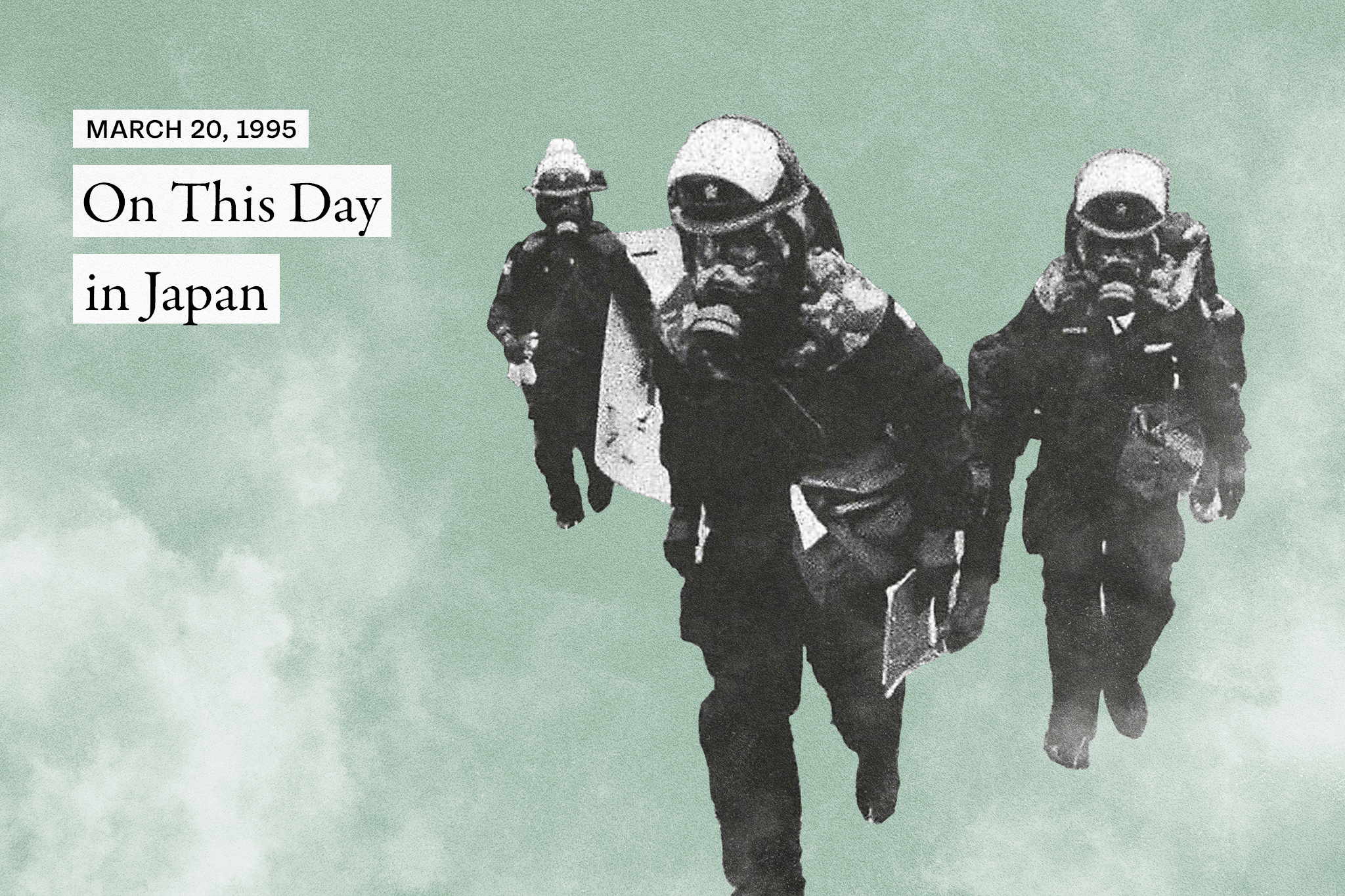

On this day in 1995, Japan experienced the most severe attack on these shores since the end of World War II. On this occasion, though, the enemy came from within rather than overseas. Five members of the cult movement Aum Shinrikyo set off packages containing sarin gas at prearranged stations near the capital’s central government district. They killed 14 people and injured more than 6,000. Had the sarin been pure, the fatalities would have been significantly higher. It was an attack that sent shock waves throughout the country.

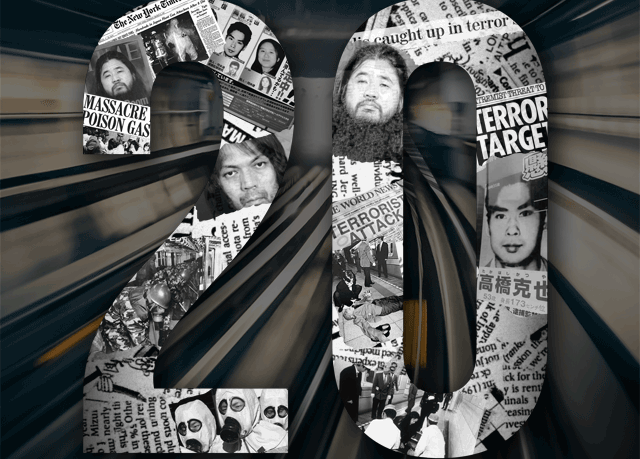

TW’s cover in March 2016 featuring Shoko Asahara and other members of Aum Shinrikyo

Shoko Asahara: The Mastermind Behind the Attack

Aum Shinrikyo, the group behind the terrorist act, was led by Shoko Asahara. Born Chizuo Matsumoto in Kumamoto Prefecture on March 2, 1955, he had infantile glaucoma from birth and, as a result, was blind in one eye and only had limited sight in the other. The fact that he could see a little gave Matsumoto power at the blind boarding school he attended, which led to him bullying other students. His ambition during his school days was reportedly to become Japan’s prime minister. After graduating, though, he studied acupuncture instead of politics and, in the early 1980s, was arrested for selling unauthorized medicine.

In 1984, Matsumoto founded the yoga school Aum Shinsen no Kai. Two years later, after his Himalayan expedition, he claimed to have achieved satori, the Japanese term for enlightenment or nirvana. As well as changing his own name to Shoko Asahara, he also renamed the organization, calling it Aum Shinrikyo, meaning the supreme truth. The focus switched from yoga to religion and incorporated various belief systems. At initiation ceremonies, which allegedly involved hallucinogens such as LSD, inductees were asked to hand over their wealth. In return, Asahara, who claimed he could levitate, would wash away their sins and bestow them with superhuman powers. They were also preparing for war with the United States that would lead to Armageddon. While it may sound ridiculous, he was able to convince some of the country’s leading intellectuals to join the group.

This included Waseda alumni Fumihiro Joyu, who became the sect’s spokesperson. “Many of us viewed Aum with a sense of mysticism,” he told Tokyo Weekender in 2016. “We felt there was something holy and extraordinary about the organization. Asahara was very charismatic and told us that if we worked for ordinary companies, we’d just be part of the crowd. With him, we could be someone important that would go down in history. At that time, Doomsday books were in vogue, and he painted us as saviors. He stimulated our self-esteem…. By 1989, I was starting to have my doubts about his unrealistic claims. I was torn between reason and my faith in the leader. I think many members felt the same.”

Murder, Mayhem and the Matsumoto Sarin Gas Attack

In August 1989, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government granted Aum Shinrikyo official religious corporation status. This was hugely important to the group as it meant receiving several privileges, including significant tax breaks. Wanting to ensure their application wasn’t thwarted, they allegedly covered up the death of Teruyuki Majima, who died at the compound after accidentally drowning while doing exercises. His body was cremated with his ashes spread over a lake. Shuji Taguchi, who knew about the cover-up, was then strangled to death when he told the organization leaders he wanted to leave. Asahara was reportedly concerned about him going to the police.

Two months after Aum Shinrikyo was granted religious corporation status, lawyer Tsutsumi Sakamoto appeared on television, raising his concerns about the fanatical leanings of the cult. A month later, he was killed in his home along with his wife, Satoko, and their child, Tatsuhiko. All three were injected with potassium chloride. Their bodies were not discovered for another six years. By all accounts, the group also had people such as television producer Dave Spector and Soka Gakkai leader Daisaku Ikeda on their assassination list. In 1993, an attempt was made on the life of cartoonist Yoshinori Kobayashi after he satirized the cult.

A year earlier, Aum sent a medical group of around 40 to Zaire to ostensibly provide aid during an Ebola outbreak. The real purpose was to obtain the virus for the cult’s biological warfare program. It failed. The organization turned to sarin gas instead. On the evening of June 27, 1994, they used a converted refrigerator truck to release a cloud of the colorless liquid in a quiet residential area of Matsumoto in Nagano Prefecture. Eight people died and over 500 were injured in the attack. Aum had two goals in Matsumoto: to kill three judges who were expected to rule against the organization in a real estate lawsuit and to test the efficacy of the sarin it produced. They would use it again just under nine months later.

Ikuo Hayashi and Tomomitsu Niimi were assigned to drop packs of sarin gas on the Chiyoda Line

Tokyo Underground

It was before 8am on what seemed like a typical Monday morning in Japan’s capital. Sleepy commuters squeezed onto underground trains with no idea what lay ahead. Among them were five men from Aum, who knew exactly what was going to happen. Wrapped in newspaper inside all of their bags was sarin gas, a chemical agent 26 times more powerful than cyanide. The intention was to kill as many people as possible. Yasuo Hayashi, who Asahara had previously suspected of being a spy, carried three packs to prove his loyalty to the cause. “I didn’t want to do it, but I knew I couldn’t run away,” he later said in court.

He wasn’t the only one who had doubts. Kenichi Hirose, a gifted scientist who studied applied physics at Waseda University, said he was “envious of the people who could just walk out of there.” Doctor Ikuo Hayashi had similar thoughts. “When I looked around, the sight of so many commuters shocked me. I’m a doctor and I’ve been working all my life to save lives. If I release this sarin now by puncturing the bag, many people could die… I thought several times that I should stop. But I couldn’t go against orders.” In the end, all five went through with it before escaping to their getaway cars. The toxin hit the victims immediately. People of all ages were described as “coughing uncontrollably, vomiting and collapsing in heaps.” By the end of 1996, the death toll stood at 13. In March 2020, Sachiko Asakawa, 56, who’d been bedridden since the attack, became the 14th victim to die.

For his book Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche, Haruki Murakami interviewed members of Aum and individuals affected by the sarin gas attack. This included Kiyoka Izumi, who worked in the PR department of a foreign airline company. “Once out of the exit, I took a good look around, but what I saw was — how shall I put it? — ‘hell’ describes it perfectly,” she said. “Three men were laid on the ground, spoons stuck in their mouths as a precaution against them choking on their tongues. About six other station staff were there too, but they all just sat on the flower beds holding their heads and crying. The moment I came out of the exit, a girl was crying her eyes out. I was at a loss for words. I didn’t have a clue what was happening.”

Fumihiro Joyu left Aleph to form his own splinter group, Hikari no Wa

The Aftermath

Fear swept through the nation. Japan’s image as one of the world’s safest nations had been shattered. Citizens were afraid to ride on trains and trash cans were removed from stations. Rumors soon started circulating that a cult had been behind the attack. On March 22, police in riot gear raided around 25 Aum offices. A week later, police chief Takaji Kunimatsu was wounded by a masked gunman. An anonymous call to a television station said that it was connected to the sarin gas attack. The country remained on edge. Mysterious fumes in the Yokohama railway system led to more than 500 people being hospitalized on April 19 and 21. Just over two weeks later, two bags of poisonous gas were discovered in the men’s restroom at Shinjuku’s subway station. In between those incidents, Hideo Murai, Aum’s second-highest ranked official, was stabbed to death by Yamaguchi-gumi member Jo Hiroyuki in front of police and reporters.

Asahara, the country’s most wanted man, managed to elude arrest for nearly two months. He was eventually apprehended while meditating in a tiny hidden room in the sect’s headquarters near Mount Fuji on May 16. It was then another month before he uttered his first words to the police. The guru admitted to being in the same room when former member Kotaro Ochida was strangled to death in January 1994. However, he added that since he was blind, he couldn’t have seen it. Ochida and Hideaki Yasuda both left the group in 1993. They then returned to rescue Yasuda’s ailing mother. For defecting, Asahara allegedly ordered Yasuda to kill Ochida or be killed himself. As the police questioned Aum’s leader, his followers devised plans to get him out.

In June 1995, Fumio Kutsumi, who claimed to be in possession of plastic explosives and sarin gas, hijacked ANA flight 857, demanding the release of Asahara. He was arrested after Hokkaido and Tokyo police units stormed the plane. Six years later, Russian Aum followers planned to set off bombs near Tokyo’s Imperial Palace as part of an operation to set Asahara free and smuggle him to Russia. It didn’t work. The guru was sentenced to death for the murder of 27 people in 13 separate indictments. He was finally executed along with 12 of his followers in July 2018. As for Aum itself, the group lost its status as a religious legal entity. It later regrouped under the new name Aleph with Joyu at the helm. After falling out with other leaders, he then created a new religion named Hikari no Wa in 2007. The two organizations, plus another splinter group called Yamadara no Shudan continue to be surveilled by Japan’s Public Security Intelligence Agency.