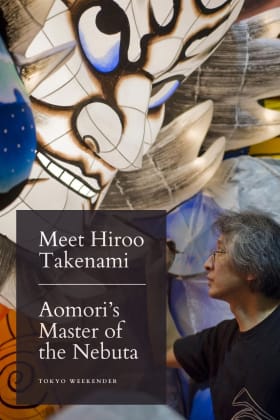

The first time I met Hiroo Takenami was at Nebuta Museum Wa Rasse in Aomori City.

The museum is dedicated to the Aomori Nebuta Festival held every August except for this year – the cursed year of 2020.

I was at the museum last autumn on a press tour with other foreign journalists. Upon greeting us, Takenami showed us the skeletal shell of an old Nebuta, which are looming, luminous floats paraded through Aomori and other cities throughout the northern prefecture during the annual Nebuta festivals.

Photo by Koji Nishikawa

Once upon a time the antique teardrop-shaped lightbulbs attached to the nest of wire were covered in vibrantly colored washi paper, creating the menacing image of an ancient Japanese warrior. Some say the origin of the Nebuta creations was to frighten off demons trying to lull farmers to sleep at the height of growing season.

As Takenami, carrying a beat-up tote bag, dressed like a professor in a black vest and jacket, leads this group of wide-eyed journalists around the museum, a bashful student comes up to shake his hand. Fellow museum-goers stop to take selfies with Takenami as if he was the float-making fifth member of The Beatles.

A Nebuta designed and created by Takenami graces the cover of the Wa Rasse museum’s brochure.

What is the Aomori Nebuta Festival?

Shawn.ccf / Shutterstock.com

The Aomori Nebuta Festival attracts 2 million visitors every year. About 20 Nebuta are ushered down the streets of Aomori by a flock of costumed dancers and encroaching crowds of people chant “rassera” – which some translate as “come join.”

Takenami, founder of the Hiroo Takenami Nebuta Institute, says the prefecture’s Nebuta festivals are a combination of a traditional Tsugaru folk event, held during the autumn harvest to ward off disasters, and the summer Tanabata festivals. This is when people write wishes for family safety and good fortune on strips of paper that are then tied to lanterns and sent floating down a river.

After the Meiji Era ended in 1912, people drew pictures on the washi-covered lanterns, which were lit from the inside with candles. People then began making doll-shaped lanterns that were paraded down the street. The matsuri – festival – element came into play after World War II, says Takenami.

Photo by Koji Nishikawa

Here at the museum the towering Nebuta (the height is limited to 7m) fill up a grand hall. Today’s Nebuta are still made from colorful washi paper attached to a wire frame – though the washi paper is mixed with synthetic material to withstand the rain. The candles were replaced by filament lightbulbs which are now replaced by LED lights powered by portable diesel generators.

The Nebuta on display at the Wa Rasse museum (named in part after the infectious chant) are from last year’s festival. The Nebuta designed by Takenami, titled “A poem written by Warrior Kinotomo put Chikata to death,” is at the center of the display.

The Nebuta won Takenami the best artist award at the 2019 Nebuta Festival. It was the seventh year in a row Takenami took home the grand prize.

Nebuta Comes to Tokyo Station

The second time I met Takenami was at the August 7 launch of the new Gransta Tokyo Square Zero event space at Tokyo Station. Clad in a smart blue suit and patterned white shirt, Takenami addressed a gaggle of Japanese paparazzi as two of his glowering demons hung over his head, suspended from the ceiling.

The installation was originally intended to welcome the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, which was postponed until next year due to the coronavirus pandemic. Takenami previously made a Nebuta for JR when the Tohoku shinkansen was extended from Iwate to Aomori and Hokkaido. JR approached Takenami to produce another Nebuta memento for the momentous occasion (the Olympics), and Takenami created two paper and light sculptures of the wind god and the thunder god.

“I thought it would be interesting to suspend a doll with lights, something like a warrior doll, something we’ve never seen before,” says Takenami. “This is a totally different experience from my previous works.”

Says the talk show host sharing the stage with Takenami, “It is said that the wind god and thunder god are deities of good harvest, and we hope that they will affect plentiful results for the people of Japan who are suffering nowadays.”

Who is Hiroo Takenami?

Born in western Aomori Prefecture in a fishing and farming community now known as Tsugaru, Takenami attended the town’s local Nebuta festival for as long as he can remember. By the age of 3 or 4 he was drawing his own Nebuta artwork. He apprenticed under a local Nebuta master at his hometown.

Takenami graduated from Tohoku Pharmaceutical University and worked as a pharmacist to support his passion for Nebuta design. In 1989, at age 30 he presented his first large-scale Nebuta. By age 35 he left pharmacy behind and now leads two or three teams of Nebuta craftsmen each year.

Standing next to Takenami’s Nebuta at the Wa Rasse museum, he instructs us journalists to lower to our knees and gaze up at the scene before us – which loosely resembles an LED version of Picasso’s Guernica in 3D – as this is the angle the sculpture appears to people at the festival.

“The eyes are looking directly at the audience,” says Takenami, now 60. “The eyes are important.”

Photo by Koji Nishikawa

How to Make a Nebuta

The eyes are the first thing Takenami imagines when designing his Nebuta, followed by the heads, which will determine the size of the float. Takenami’s range of interests – history books, movies, kabuki theater, Impressionist paintings, stained glasswork of European churches – all reflect in the completed project. Takenami is particularly influenced by 14th-century sculptor Unkei, known for the masculine Buddha figures at the south gate of Todaiji Temple in Kyoto.

“The characters must come from Japanese tradition,” says Takenami. “But the color and design come from many inspirations.”

The imagery of Takenami’s Nebuta at Wa Rasse is based off a Japanese waka poem about an aristocratic warrior poet named Kinotomo called upon to dispel four demons. Kinomoto wrote poems about the greatness of the emperor and fought off the demons with his royally inspired verses.

Looking at the Nebuta, the cuticles of the fingernails, the buckles on the warrior’s boots and the grips of the demons’ swords are designed in ornate detail. The colors are bold and powerful, but unlike the cartoonish caricatures of the other floats, Takenami’s demons and warriors look as if they erupt from an ukiyo-e painting. Which makes sense since Takenami says he strives to create the same 3D illusion that Hokusai affected with his paintings.

Photo by Koji Nishikawa

“I wanted to show the power of the Japanese poem,” says Takenami. “The message is the pen is mightier than the sword, and can resolve the situation peacefully.”

During his time at both Tokyo Station and at the Wa Rasse museum, Takenami stays behind, gently greeting any who wish to speak with him, before finally leaving with a deep bow and wave.

Says our guide at the Wa Rasse museum, “It’s been many years since a Nebuta master earned this much attention.”

Takenami’s installation at Gransta Tokyo at Tokyo Station is on exhibit until September 22, 2020. (Now closed)

Feature photo by Koji Nishikawa

Updated On July 6, 2021