Sex workers advertised their trade in all sorts of ways throughout the millennia. In the 17th century, Dutch women offering sexual favors to sailors carried red lanterns, from which we get the phrase “red-light district.” There are also stories of undetermined veracity about sex workers in Ancient Greece wearing special sandals with metal studs on the soles that imprinted the word akolothi (follow me) on the ground as they walked. And then there are the Japanese asobi who during the Heian period (794 – 1185) attracted clients through songs sung on the water. But there is so much more to their story.

All Aboard the SS Sex Work

In the late 11th century, areas around the Yodo River began to be populated by small communities of women called “asobi” who put the “pleasure” in “pleasure cruise.” The Yodo River was an important passageway from the, then, capital of Kyoto to Osaka and towards the Seto Inland Sea, but it was also a popular spot for royals and aristocrats to relax on their lavish boats, drinking, eating and enjoying the company of beautiful women. And if they forgot to bring one along, the asobi were there to help with that.

It typically worked like this: The asobi would set out on the river in a boat of their own, which carried the principal girl, her assistant with a parasol and a choja matron who protected the girls and took care of the finances and the rowing. On the water, the main asobi would sing so-called imayo songs that varied in style and topic, ranging from flirty folk tunes to refrains about a mother’s love for her children or pious odes to the Buddha. If all went well, the women would get a signal from a pleasure boat and be invited aboard where the songs continued, eventually leading to sex and an exchange of money or bushels of rice (delivered at a later date).

Because the asobi were foremost viewed as talented imayo performers and because they conducted their business during the day, their activities were not seen as strictly prostitution and, for a while at least, were socially acceptable. Still, there was a time when asobi were more than just tolerated. Once, they were respected and revered.

Goddess Ame no Uzume

From Shamans to Courtesans

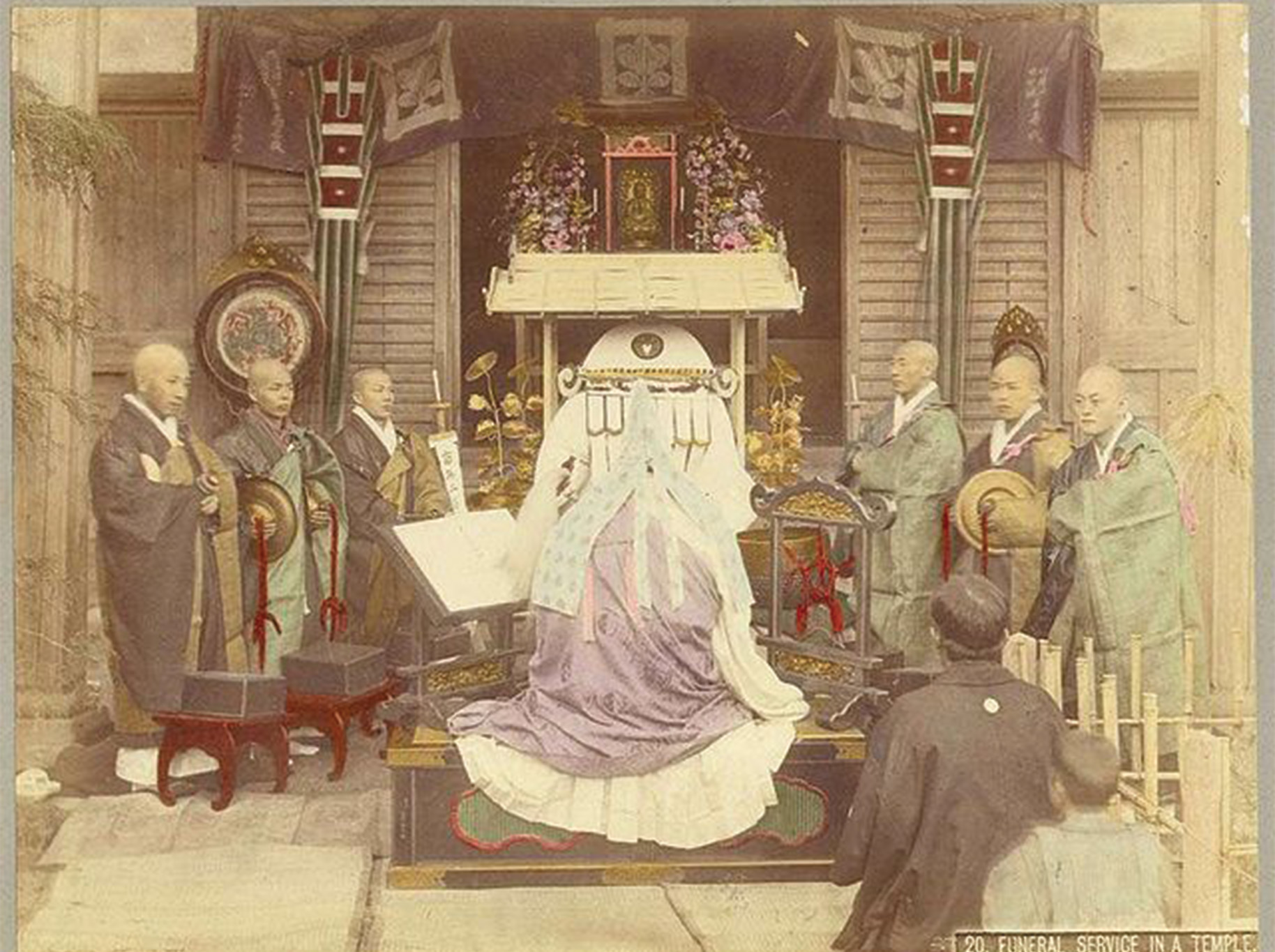

The asobi did not start out as sex workers. Until the 8th century, they were priestesses performing an important function in the direct service of the Imperial Court. In their initial incarnation, the asobi performed funeral dances and chants to appease souls of deceased royals and ensure their prosperity in the afterlife. They were actually one of the few people with direct access to imperial coffins, and their job was deemed so essential that they were excluded from paying taxes.

Interestingly, their transition from shamans to sex workers, to which we’ll get in a moment, was sort of in line with their heavenly patron. The asobi claimed descent from the Shinto goddess Ame-no-Uzume. One of the most important myths about Ame-no-Uzume concerns the sun deity Amaterasu, who once hid away in a cave, plunging the world into darkness. By being instrumental to getting Amaterasu out of the cave, Ame-no-Uzume came to represent renewal, transformation and the power to drive away evil. The link between her cult and rituals for the dead is only to be expected.

But for all of that, Ame-no-Uzume wasn’t a particularly stuffy deity. The way she got Amaterasu out of the cave was by partially stripping and doing a funny dance, causing the other gods to laugh and roar and intriguing Amaterasu enough to peek out of her hiding place. As such, Ame-no-Uzume stands at the crossroad between solemnity, mirth and eroticism. But she isn’t why the asobi turned to prostitution.

The Relegation of Native Japanese Beliefs

The asobi’s loss of priestess status can be linked with the rise of Buddhism in Japan, which quickly established a monopoly on the country’s funerary rites. In fact, even today, Buddhism is sometimes called “the religion of death” in Japan because almost every single funeral custom in the country is Buddhist in origin. The popularity of Confucian thought also added to the asobi being viewed less favorably over time, as they didn’t produce anything material like crops. Ultimately, they were expelled from the Imperial Court. They still had their imayo songs, and were in fact the only group allowed to perform them, but it wasn’t enough to support them, which is why they started engaging in sex work.

There is a feminist reading of their loss of status (even when prostitution wasn’t actively frowned upon in Japan, sex workers were usually one of the lowest social classes) seeing as Buddhism and Confucianism were dominated by male figures. But they were also something else: representatives of Chinese (i.e. foreign) culture.

When you look at the contents of imayo, you do find plenty of songs about Buddhist topics, but the earliest examples were all about traditional Japanese poetry, native legends or local fauna and flora. The Buddhist themes came later. As such, the asobi can be seen as representatives of indigenous Japanese beliefs that for a time centuries ago were supplanted by other faiths and schools of thought from the Asian mainland. They, of course, never went away, but they definitely experienced highs and lows throughout their millennia-long history. The asobi were simply unlucky to be there during a particularly bad low.