They have been called the greatest privatization success story in Japan’s history: railways. Their on-time record is the envy of the world. In its best year in nearly six decades of service, the Tokaido Shinkansen carried more than 477,000 passengers a day along its 550-kilometer route between Tokyo and Shin-Osaka stations –– and yet the average delay per train was less than 1 minute. It’s hard to fathom how such a busy rail corridor could achieve such precision. What made it possible? One key moment: the break-up of the government-owned Japanese National Railways into regional Japan Railways companies in the late 1980s. Today, the efficiency and safety records of JR and the many of the country’s other private railway operators suggest that the government had a minimal role in developing rail transport. A closer look, however, reveals a more complex story about the evolution of Japan’s modern railways.

Steam engine on the Shin’etsu Line stopping at Isobe Station. ca 1901-1902.

Laying the Tracks

Japan’s first railway route officially opened on the morning of October 14, 1872. Under a clear sky, a steam locomotive with nine cars, carrying Emperor Mutsuhito, government leaders, diplomats and other dignitaries, made its way from Tokyo’s Shimbashi Station to Yokohama Station. It would be some time before the 53-minute trip was affordable to the masses. At the time, a third-class ticket between the only two stations cost the equivalent of ¥5,000 today. (The same trip now takes less than 30 minutes and costs under ¥500.) The train cars had few amenities and notably lacked toilets, and stories spread of passengers making use of open windows to answer the call of nature. One former samurai is said to have been fined for sticking his buttocks outside to fart. But these were growing pains for a new form of transportation that would have a lasting impact, connecting farflung regions and urban centers and setting the country on a path to modernization.

The Shimbashi-Yokohama railroad was the result of an ambitious public-works project spanning several years. The locomotive, train cars and rails had to be imported from the UK. Before long, the private sector came barging in. First among the private railway entrants: Nippon Railway, in 1881. Its model of operating trains between Tokyo’s Ueno Station and Tohoku’s Aomori, but leaving the track-building to the government, would be widely copied by others. In a country whose land is more than two-thirds mountains, imagine the savings of not having to bore tunnels or cut paths through forests and the peace of mind of not having to scoop up land through eminent domain.

The 1892 Railway Construction Act (RCA) amounted to an endorsement of that arrangement. The RCA channeled public funds to new lines in rural places, enticing private railways to expand into faraway regions that otherwise were too sparsely populated to seem worth the investment. The government saw railroads as a way of tying together –– economically, geographically, culturally –– the country’s four main islands. It might have funded a national rail system on its own had the public coffers not been depleted by the Satsuma Rebellion, a samurai uprising that was crushed in 1877 and dramatized by the Hollywood film The Last Samurai. By 1905, more than three–quarters of Japanese railways were privately owned.

Picking Up Steam

But the government soon stepped in to assert control. Citing train delays during the Russo-Japanese War, the government announced that it was nationalizing the railways in 1906. A Ministry of Railways, formed in 1920, was put in charge of the Japanese Government Railways (JGR) and the newly-created Board of Tourist Industry tasked with promoting railways to attract foreign travelers. New lines opened and innovative ideas flourished. Between 1906 and the end of World War II, the publicly funded Railway Research Office developed rust-resistant materials, made improvements to the efficiency of engine boilers and even invented a type of paint to discourage bees from building hives that interfered with train brakes.

JNR 583 Series train by Wanted-man, licensed under CC BY 4.0, 1985.

By 1949, when officials decided to replace the Japanese Government Railways with the Japanese National Railways (JNR), roughly 70% of the country’s train lines were state-run. For a while, things went smoothly for the government. Car ownership was still more than a decade off, and trains had a head-start in becoming the country’s dominant mode of transportation.

In the 1960s, more cars took to the roads, and JNR’s operations suffered. Service disruptions were all too frequent: Unions protesting against onerous workloads and meager pay rises staged strikes, slowdowns and walkouts. In response, JNR hiked train fares and cut back on rush-hour trains, angering the public. Trains were vandalized or set on fire. In one instance, an enraged mob took a stationmaster hostage. By 1981, despite efforts at reforms, JNR’s debt had swollen to a staggering $87 billion and its standing with the public was at a historic low. With little hope of a turnaround, the government resorted to privatizing JNR in 1987, making way for the former state-run railways to reorganize as regional JR companies. The government was no longer in the train business. But it was hardly a clean exit.

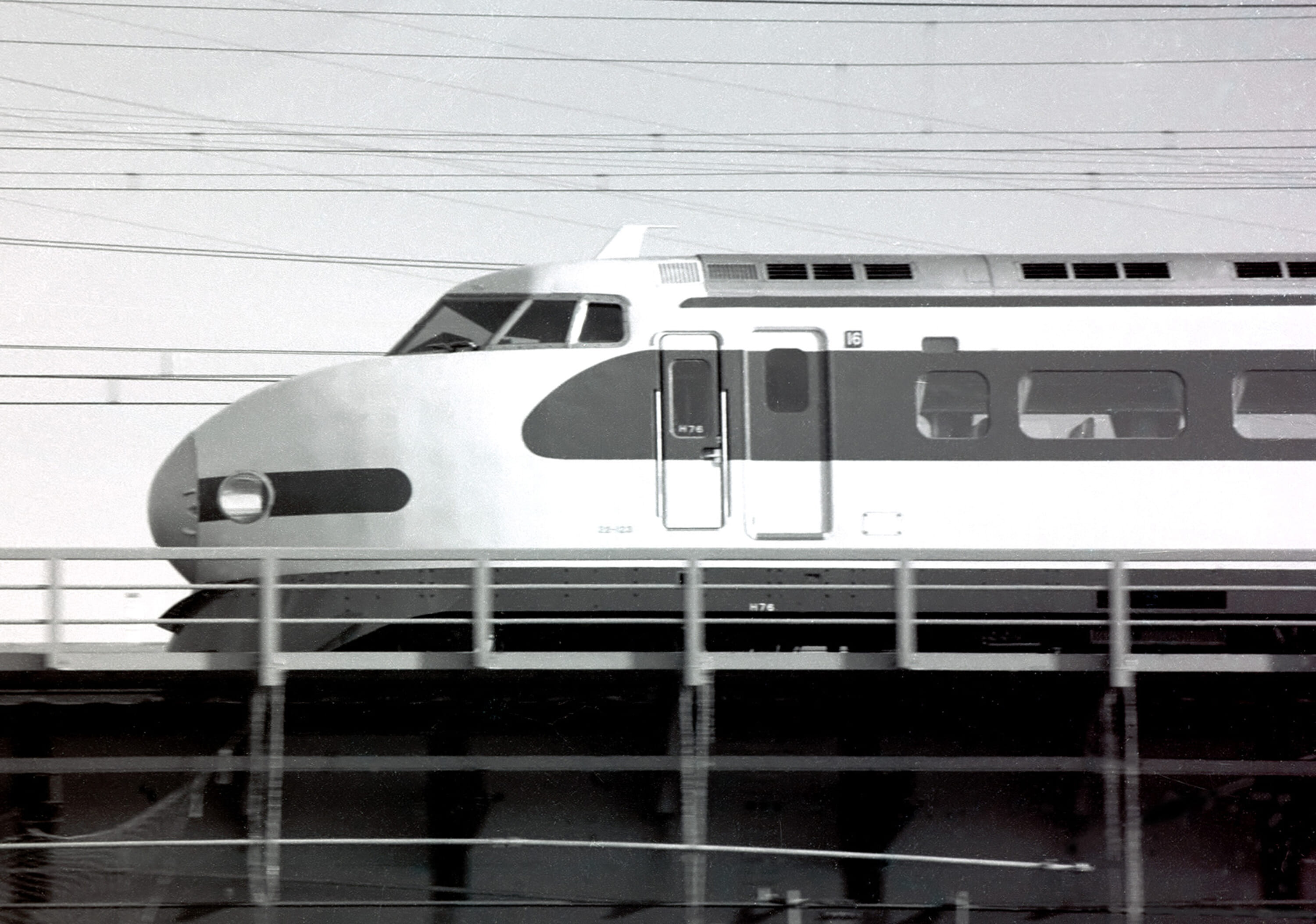

A specially decorated 0 series shinkansen running as an imperial train between Shin-Yokohama and Tokyo by Shellparakeet, licensed under CC BY 4.0, 1977.

Running Smoothly

Government officials knew better than to hand over a broken train system with spiraling debts and expect the newly privatized JR companies to have a quick fix. Taxpayers had to chip in, shouldering ¥14 trillion of JNR’s debts. For railways in less-populated areas, the government devised a special subsidy program that treated trains as a public good. With the extra funds, regional rail operators could keep fares low while paying for costly overhead –– ensuring that traveling by train anywhere from northern Hokkaido to southwestern Kyushu remained affordable.

Linear Chuo Shinkansen L0 improved test car by w-ken0510, Pixta

Meanwhile, the government continued to bet heavily on new train technologies. The state-funded Railway Technical Research Institute (RTRI), which took over for a former government lab in 1986, has explored ideas for safer, speedier, more comfortable trains that are also more energy-efficient. One high-profile RTRI-led project: next-generation magnetic levitation (maglev) Shinkansen. These ultrafast trains rely on magnets to lift off their tracks, zipping forward on special guideways at frictionless speeds of 600 kph. When Central Japan railway completes the first phase of its maglev line, the new Linear Chuo Shinkansen will shorten the one-hour-and-39-minute Tokyo-Nagoya trip to just 40 minutes.

The government’s involvement is, of course, only part of the Japanese rail industry’s story. Private enterprise deserves plenty of credit for the sector’s stellar reputation. Today more than 100 privately owned rail companies manage much of Japan’s 27,700 kilometers of track. Many of those businesses have turned train stations into city-building projects, creating jobs, lifting local economies. Entire communities, with shops and schools and parks, have sprung up along railway lines in once out-of-the-way places. There are now more luxury sleepers and fine-dining cars and tourist trains than ever before stopping in small towns and rolling through stunning landscapes. In the next few years, plans are afoot for Shinkansen extensions in western Kyushu, north-central Japan and Hokkaido that could improve access for remote communities and even bring in tourists. Overlapping public and private interests in Japan’s railways has never been free of messy entanglements, but they’ve also managed something that even early visionaries could not have dreamed of: a national train network that ranks among the world’s finest and restores faith in the romance and wonder of rail travel.

This article was originally published in the special issue En Route.

Updated On November 15, 2023