Japan is not typically known for progressive gender equality policies. As recently as 2023, Japan ranked the lowest among developed countries regarding gender equality under the law. Women were not granted suffrage until 1945, and the country’s gender pay gap remains the largest amongst all G7 countries.

That being said, throughout history there have been several pre-eminent women spearheading the country’s women’s movement. To celebrate International Women’s Day, we’ve put together a list of five influential Japanese feminists, from poets to pharmacologists, who have helped reform the country’s misogynistic policies and led the charge in the liberation of women across the country.

Noe Ito (1895-1923)

Feminist and anarchist Noe Ito is best known for her work with Seito, a feminist magazine of which she became Editor in Chief at only 18 years old. Based on the 18th Century English “Blue Stocking Society,” Seito was founded in 1911 by five women, including pioneering feminist Raicho Hiratsuka, and was dedicated to showcasing female literary talent. Under Ito’s helm, the magazine also became a radical force for tackling the social issues faced by women from all walks of life.

This involvement with Seito precipitated Ito’s involvement with Sakae Osugi, an anarchist political and cultural commentator. Together they worked on political writings and activism and developed a controversial romantic relationship.

Following the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, Ito and Osugi, along with other leftists, anarchists and the immigrant Korean population were targeted by the police raids that took place in the wake of this disaster. The pair, as well as Osugi’s 6-year-old nephew, were all strangled to death on September 16, 1923. Ito was only 28 years old. Despite her untimely death, she established herself as a critical figure in both the feminist and anarchist movements in Japan.

Raicho Hiratsuka (1886-1971)

Although primarily remembered for her stewardship of Seito, writer, political activist and anarchist Raicho Hiratsuka was also more broadly involved in Japan’s 20th century women’s movement. The daughter of a high-ranking civil servant, Hiratsuka’s position in society afforded her the privilege of a university education, permitted by her father on the condition that she enter via the Home Economics Department. It was her time at Japan’s Women College that began Hiratsuka’s interest in Zen Buddhism, bestowing within her a belief in the infinite possibilities of life.

Following her university graduation, Hiratsuka joined a women’s literary group, where she became involved with one of the group’s lecturers: a married man who chronicled the details of their unconsummated affair in what became a best-selling novel titled Baien (Smoke, 1909). Hounded by the press, Hiratsuka, once the daughter of privilege, became a figure of scandal.

This precipitated a turning point in Hiratsuka’s activism; she was encouraged by literary critic Ikuta Choko to begin a literary journal for women: Seito. Some five years later, Hiratsuka also founded the New Women’s Association in 1920, the first women’s organization in Japan to call for female suffrage. After a visit to a textile factory in Nagoya to inspect the conditions for female workers, Hiratsuka became incensed by the notion that women must, and should, act collectively to gain political rights and social reform. It was through the efforts of her leadership and this group that the ban against women participating in legal organizations was eventually overturned.

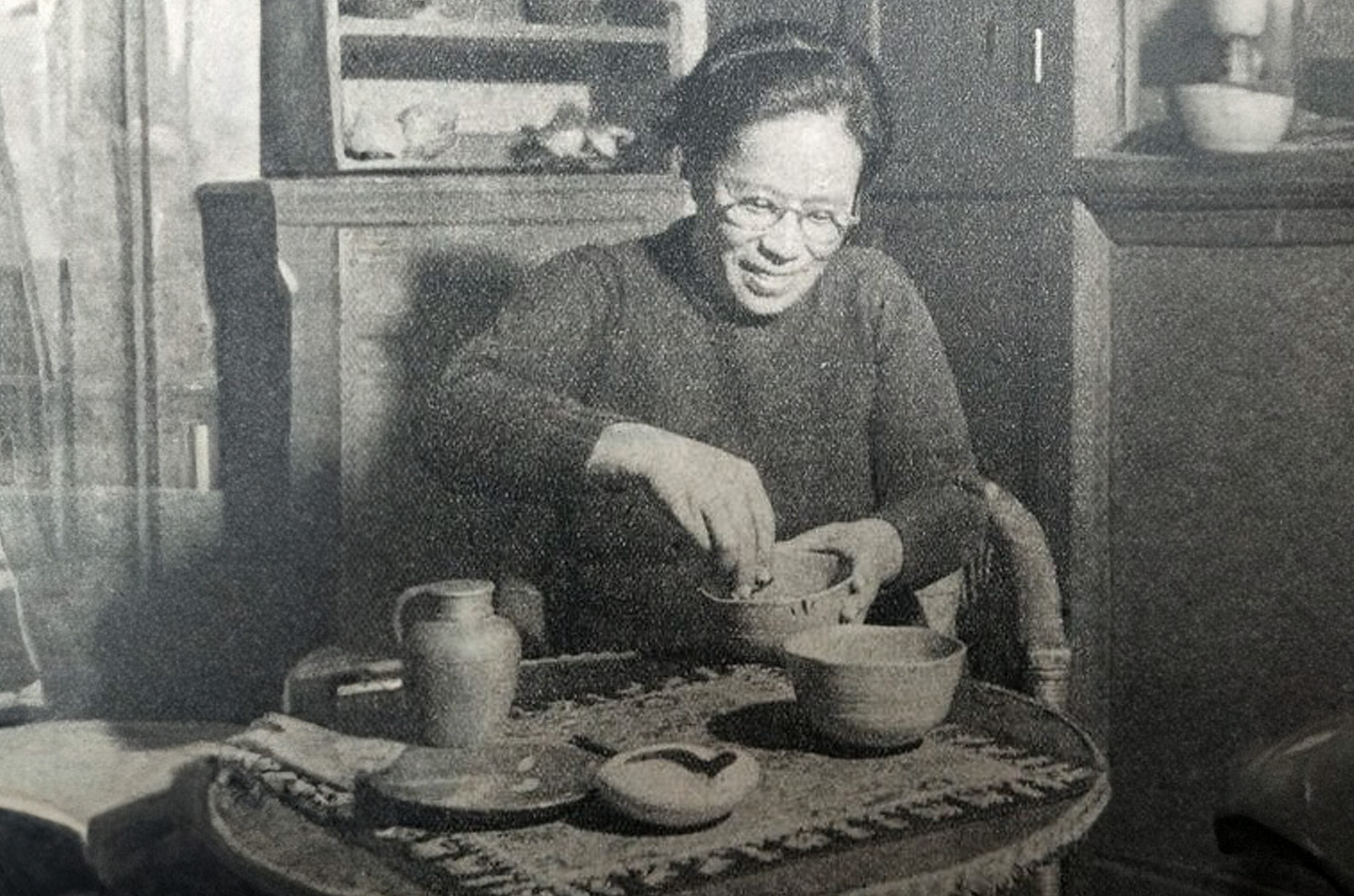

Taki Fujita (1898-1993)

Taki Fujita was a Japanese educator and women’s rights activist. Despite being a traditional, Christian judge, her father believed it essential that his daughter receive a modern education, and Fujita received schooling at both Tsuda College, a private university for women of which she would later become president, and Bryn Mawr, a liberal arts college in Pennsylvania. It was during this time spent in America that Fujita first became engaged in international affairs, and committed herself to the fight for equality between men and women.

Alongside American educator Lulu Holmes, Fujita co-founded the Japanese Association of University Women in 1946, and she served as the first president. The group, which is still running today, aims to improve the social status of women and girls in Japan, to promote life-long education for women, and to enable female graduates to effect change by way of their expertise.

Made president of the League of Women Voters in Japan in 1956, Taki was incredibly active in the fight for female suffrage in Japan, translating Western suffrage writings into Japanese to promote their circulation around the country. Despite suffering from car accident-induced injuries in her seventies, Taki headed the Japanese delegation to the World Conference of the International Women’s Year in Mexico City in 1975. She was later awarded the First Class Order of the Sacred Treasure for her services to women across the country.

Akiko Yosano (1878-1942)

Born in 1878 into a prosperous merchant family near Osaka as Ho Sho, poet Akiko Yosano was, and remains, one of Japan’s most controversial female poets.

Despite being the family member most responsible for the family business from age 11 onwards, Yosano’s interest in literature began to bloom in her childhood. She read extensively from her father’s library and subscribed to the monthly literary magazine Myojo, which she would later come to edit.

Yosano’s first collection of tanka poems, Midaregami (Tangled Hair), was published in 1901 and is her best-known work. Yosano’s tanka were renowned for her unusual expression of femininity. Her work espouses a revolutionary image of womanhood, posing challenges to the traditional patriarchal structures within Japanese society. While the collection was denounced by critics at the time, its passionate individualism marked a significant contrast to the other poetry of the Meiji period, and became a lighthouse for other free thinkers at the time. Throughout her career, Yosano is thought to have written somewhere between 20,000 and 50,000 poems, as well as 11 books of prose — although the latter have been largely neglected from scholarship.

A lifelong advocate of women’s education, Yosano helped to found the Bunka Gakuen in 1923, where she also became a lecturer and the first dean. Throughout her life, Yosano helped many other aspiring writers gain a foothold into the literary world, and translated the Japanese classics into modern Japanese for wider circulation.

Misako Enoki (1945-present)

A feminist, political activist and pharmacist, Misako Enoki played an invaluable role in the legalization of the birth control pill in Japan in the late 20th century.

In 1970, Enoki first became involved in a translation group referred to as the “Urufu no Kai,” or “Wolf Group” — a reference to the English writer Virginia Woolf. The group translated a series of essays that had first appeared in the US under the title Women’s Liberation: Notes from the Second Year. Enoki began distributing a pamphlet calling for the legalization of the contraceptive pill under the group’s name — although this led to discontent from members of the group who opposed her views.

In May 1972, Enoki attended the “Ribu Conference” (ribu standing for liberation), where she recruited women to form a protest group called Chupiren (Women’s Union for Liberalization of Abortion and Legalization of the Pill), sometimes referred to as the Pink Panthers. This radical wing of the Japanese feminist movement organization demonstrated a series of campaigns addressing the concerns of women, including legal rights in divorce and marriage, access to birth control, abortion and equal pay. The group often wore pink hard hats and white military-style uniforms to attract media attention, and performed guerrilla style publicity stunts such as confronting unfaithful husbands in their office

Despite the media ridicule they often received, under Enoki’s leadership, Chupiren played an important role in raising the profile of women’s issues, particularly on the long to the eventual legalization of the contraceptive pill at the turn of the century.

Related Posts:

- Spotlight: The Life and Legacy of Feminist Activist Noe Ito

- 5 Trailblazing Japanese Women Writers

- Fighting for Modern Japan: The University Protests of 1968–69

Updated On March 8, 2024