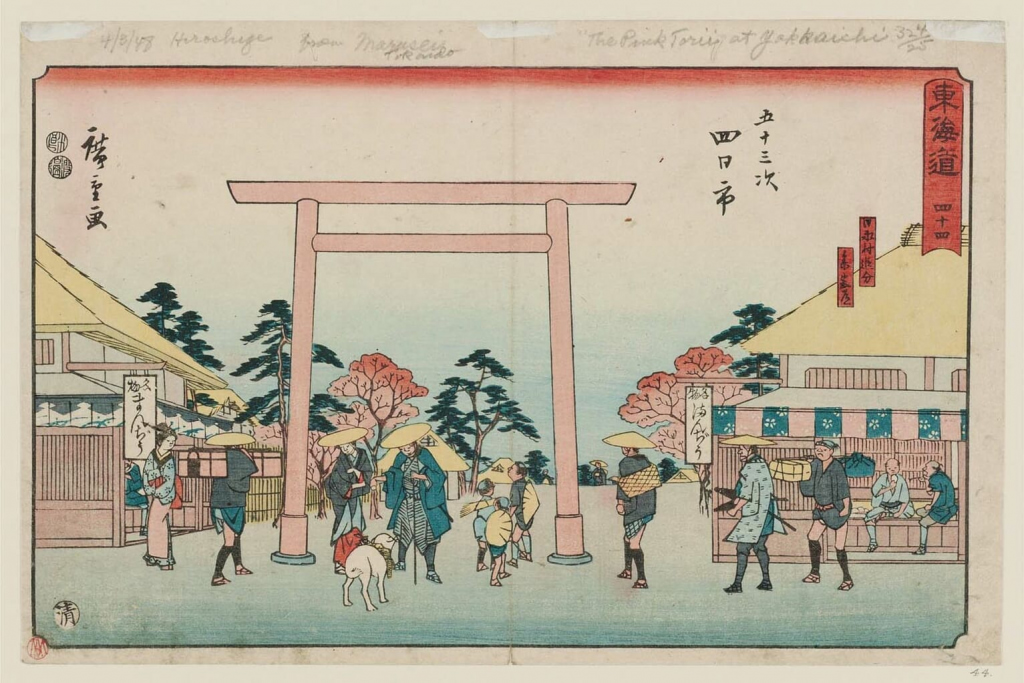

The Ise Grand Shrine in Mie Prefecture is such an important place of Shinto worship in Japan that it’s sometimes referred to simply as “The Shrine” (Jingu). Venerating the sun goddess Amaterasu and housing one of the Imperial Regalia of Japan, The Shrine has been attracting tourists and worshippers for two millennia now. But it wasn’t always the easiest place to get to. During the Edo Period (1603-1868), commoners actually needed special consent to leave their places of residence and go on the Ise pilgrimage. Sometimes they didn’t feel like waiting for permission and just went anyway, often in huge numbers, openly defying the laws of the land in more ways than one.

Ise (Ujiyamada), Mie, November 27, 2019. People worship to the Kotai Jingu, or main shrine, of Ise Jingu. Photo credit: b-hide the scene via Shutterstock.com

Turning a Sacred Pilgrimage Route into Fury Road

Okagemairi, also known as nukemairi, was the social phenomenon of sudden, mass pilgrimages to Ise without official permission from the authorities. Since Japan had to come up with two separate names for it, you can probably guess that this happened more than once. And, indeed, these kinds of abscondences were extremely common during the Edo Period. At the low end, they numbered in the thousands, but the biggest ones, which were recorded in 1650, 1705, 1771 and 1830, saw 2-3 million people descending on Ise.

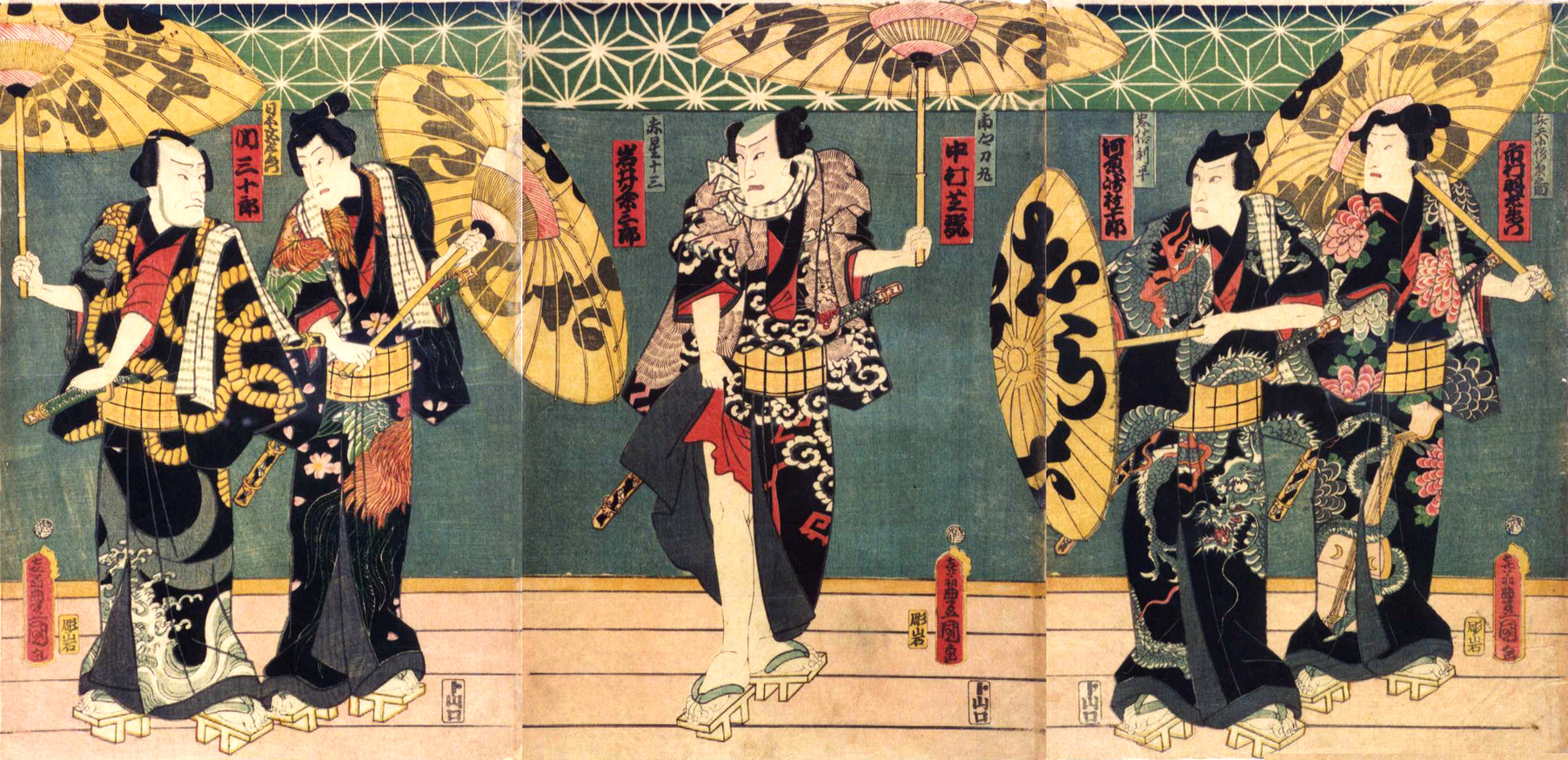

The problem with that, though, wasn’t accommodating the many travelers. It was what they did on their way to The Shrine, which often included gambling, pickpocketing, starting fights, robbery and visiting brothels. Many kabuki plays such as Shiranami Gonin Otoko (The Story of Five Notorious Thieves) by Kawatake Mokuami are actually dedicated to the subject of people turning into brigands on the way to pray to the most important deity in the Shinto pantheon.

A print by Utagawa Kunisada depicting the kabuki play Shiranami Gonin Otoko (The Story of Five Notorious Thieves). Image from Wikimedia Commons.

A Rare Source of Freedom

In the rigidly hierarchical society of feudal Japan, everyone was supposed to know their place and keep an eye on their neighbors to ensure everyone who wasn’t rich (meaning the vast majority of the country) was equally miserable. A pilgrimage, mass or otherwise, offered a way to escape that. Once they were outside their home provinces, the pilgrims were among strangers and could thus cut loose.

Combined with a break from their work life, it created a powerful psychological effect that gave them a rare feeling of freedom. Wanting to experience that feeling so badly, many didn’t wait for such things as permission. They just went, surviving on the road through the very thing they were seeking, freedom. Specifically, freedom from feeling they had to obey the law. The lawlessness exhibited on the road to Ise was actually a symptom of a deeply oppressed society that was just looking for a release valve.

Another release was through visiting the many brothels near Ise. Some sources estimate that there were as many as 1,000 prostitutes in the vicinity of Ise servicing customers drunk on their first real feeling of freedom. And probably copious amounts of sake. With time, visits to The Shrine became so synonymous with sex that a combination joke and urban myth emerged claiming that anyone who cheated on their spouse during an Ise pilgrimage would become fused to their lover’s body. The only way to get unstuck was for the cheaters’ conjoining to be witnessed by 1,000 people.

The Parlor of a Brothel. Ukiyo-e by Utagawa Toyokuni

The Dark Side of Pilgrimages as Social Rebellion

In the 18th century, spontaneous trips to Ise became especially popular with teens as a way to rebel against their parents and society. While these young people were still close to Edo (modern-day Tokyo) during the early days of their freedom-filled travels, they probably were having a blast. But as soon as they got far enough from the seat of power and organized law enforcement, the party quickly stopped.

In short time, the rebellious teen pilgrims became targets of slave traders who kidnapped and sold the girls to brothels and boys to far-off farms where they were reportedly treated worse than livestock. Slavery had been outlawed in Japan by that time, but a simple falsified document of debt and indentured servitude provided an easy loophole that fueled one of the darkest “industries” of the Edo Period. In many cases, the parents assumed that their child was “spirited away” by the gods when in fact they were taken away by humans on the road to meet the gods.

The Edo Shogunate’s control of travel ended with the Meiji Restoration in 1868. By that point, the pilgrimages started shedding their darker history and helped establish an infrastructure for travelers and a booming domestic travel industry that’s robust to this day.