In the Osafune neighborhood of the town of Setouchi, in Okayama Prefecture, a centuries-old cultural tradition continues to this day. It is the practice of swordmaking, and the area has quite a pedigree. Of the 111 swords that have been designated National Treasures, 55 of them are Bizen Osafune swords (Bizen is the town just next to Setouchi, and is also well known for its distinctive pottery.)

At a recent seminar held at a trade event for Okayama Prefecture, Tetsuya Ueno, a sword expert and chief curator of Hayashibara Museum of Art in Okayama City, explained some of the history and craftsmanship that goes into the manufacture of a traditional Japanese sword. As Ueno explained, the Bizen Osafune school of swordmaking rose to prominence in the 12th and 13th centuries, thanks to Okayama’s wealth in the raw materials needed for swordmaking, its relative freedom from natural disasters such as earthquakes, and its proximity to trade routes.

Although samurai dramas depict warriors whipping out their swords and clashing blades almost at the drop of a hat, Ueno said that during most periods of history, it was considered a greater skill for samurai to be able to bring an end to fighting without violence. That said, sword experts have noticed that blades made in the Bizen Osafune region actually differ in size and shape during historical periods of war and peace: swords made during wartime are larger and more sharply pointed than those made during eras of relative peace.

No longer needed as an implement of violence, Japanese swords still represent the tradition of bushido, the way of the warrior, and they are the product of the labor of at least seven different artisans.

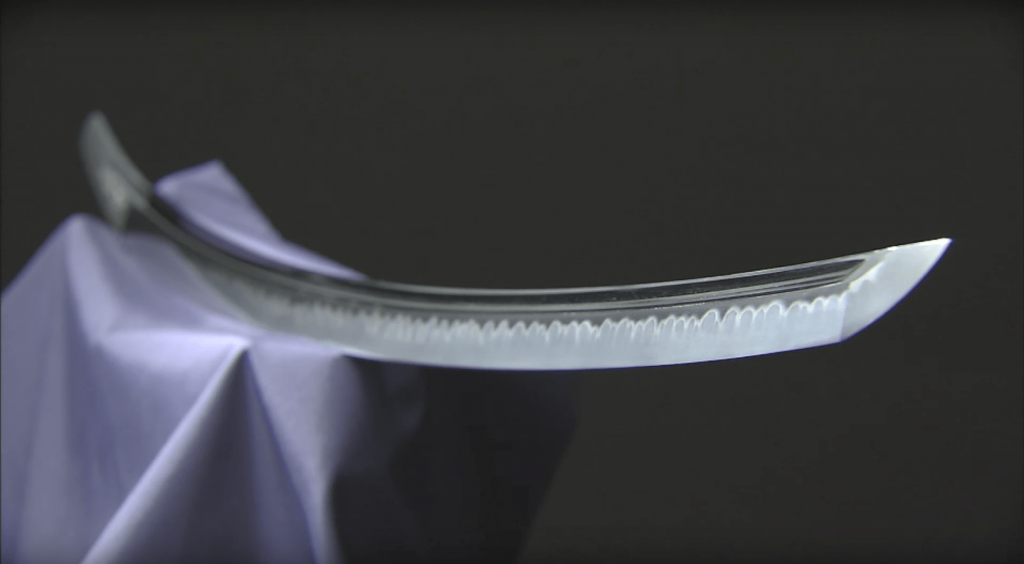

A video recently produced by the city of Setouchi delves into the work performed by these craftspeople. It begins with the katanaji, the swordsmith who beats the molten metal into the basic shape of a sword. Then, the togishi sharpens and polishes the blade, a process that can take anywhere from 80 to 100 hours. The work of the shiroganeshi comes next: this artisan makes the blade collar out of gold, silver, or bronze – this item keeps the sword from touching the scabbard directly. The scabbard for the sword is made by the sayashi, a specialized wood worker. A nurishi, or lacquerer, then coats the scabbard in multiple coatings of lacquer. This process involves more than a dozen coatings, and takes two to three months. The chokinshi is responsible for engraving the blade, blade collar, and blade guard with words or pictures. Making the hilt and the binding of the sword is the job of the tsukamakishi, who decorates the blade with brocade patterns.

All together, almost a year’s labor goes into the making of one sword, and the product of this collective work costs about as much as a car – a standard automobile in the case of basic swords, and a luxury car in the case of more elaborate weapons. If you visit Setouchi City, you can go to the Bizen Osafune Japanese Sword Museum, where you can see first hand how these artisans keep this venerable Japanese tradition alive. And if you have the funds available, you can order your very own sword.