I’m only 10 minutes into my interview with Ushio Amagatsu, founder of butoh dance company Sankaijuku, when he stands to demonstrate how he choreographs the abstract movements of his productions. So far, our conversation has also been pretty abstract, so I’m quite relieved that he’s chosen to show rather than tell at this point.

“When creating a piece, my approach is completely different to other butoh companies,” he says. “I don’t use mirrors or music in the rehearsal room. Instead, I create virtual settings for each movement. Even if it is only two seconds long, every movement has an imagined story attached, and in this way the dance is built on layers of meaning.”

Stretching his right arm out in front of him while pointing his forefinger towards the wall opposite us, he elaborates: “Imagine a very thin thread attached to your finger and dropping down. A miniature version of yourself is hanging at the end of this thread. You, in turn, are also hanging by a thread, and being carried by a bigger, giant version of yourself.” He takes a snail-paced but purposeful step forwards, keeping his arm and finger in situ. “If you walk a single, small step in this context, you are carrying yourself, but you are also carried by yourself. This a very basic etude to describe how I choreograph a step.”

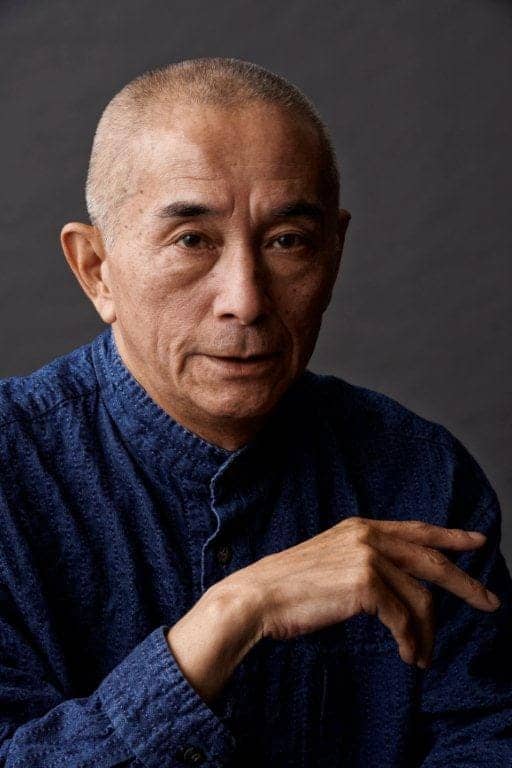

Ushio Amagatsu. Photo by Shintaro Shiratori

If you’ve ever watched a butoh performance, you’re likely nodding your head as Amagatsu’s description calls to mind this minimalist yet deeply expressive form of contemporary dance. Founded in the 1960s by Hijikata Tatsumi and Ohno Kazuo, butoh (which means “the dance of utter darkness”) was born out of the confusion and desperation felt after World War II and the atomic bomb attacks on Japan. It was also an attempt by Tatsumi to return to Japanese aesthetics as he felt the country was becoming too heavily influenced by Western dance styles.

“It’s characterized by intense, obscure movements performed by dancers with shaved heads and their entire bodies painted in white”

It’s characterized by intense, obscure movements performed by dancers with shaved heads and their entire bodies painted in white. The performers are at once ghostly, unnerving, and captivating. In 1987, The New York Times summed it up as “the avant-garde dance form that today is Japan’s most startling cultural export,” and stated that “it sets out to assault the senses.”

Decades later, Amagatsu’s company Sankaijuku, which he formed in 1975, is keeping this startling cultural export alive on stages around the world. The award-winning group has performed in 45 countries and visited more than 700 cities, and every second year they premier a new piece at Theatre de la Ville in Paris. This month, on November 25 and 26 (2017), they’re performing their piece “Meguri – Teeming Sea, Tranquil Land” at the New National Theatre, Tokyo, marking the first time the production has been shown in a national theater.

Sankaijuku’s “Meguri” performance

While Amagatsu’s style of butoh still has much in common with the original style, he is quick to point out that, as a second-generation artist, his subject matter differs to those of the first-generation artists, whose “experiences were very rooted in World War II.” As a result, Amagatsu says he began his own journey by asking the question, “What is butoh to me?” The answer he arrived at – which he has written about in several books (originally in French, and since translated into Japanese) – is that it’s a dialogue with gravity. “I think of the body with and without force; with and without tension. The traverse between these points really has an important connection to my style of butoh.”

He may not be as concerned as his predecessors were about the war, but it’s clear Amagatsu still pours a great deal of philosophy and existentialism into his work. Still, his aim, he says, has always been to create simplicity on stage. And as we continue to speak, I find some of his answers have a surprisingly practical slant.

I ask him how he feels when he dances.

He replies, “Empty.”

“Like meditation?”

“No. Because if you’re thinking of something, your body’s movement gets delayed. If you have a void mind, the dancer can effortlessly follow what he has rehearsed in the studio.”

I’m curious about the white make-up his dancers are cloaked in on stage.

He explains, “White make-up existed before us, for example in the masks of the noh theatre and kabuki actors. But it also existed in other countries outside of Japan. I came to understand it as a way of removing ourselves from reality, and of removing individual personalities on stage. Of course, the white paint also reflects the light very well. So you can make the dancer’s body like a canvas.”

I also want to know why Sankaijuku only employs male dancers.

He chuckles and says he’s been asked this question many times. “Please believe me, there is no discrimination against women. It was purely coincidental.” As it turns out, the reason is quite simply down to the fact that when he founded the company, he held a one-year workshop, and out of the 30 dancers who applied, only three men stayed for the full course.

As we wrap up our interview, he treats me to one more flicker of his abstract side. But this time his words are more inspirational than enigmatic. I ask what he likes to do when he’s not dancing. He replies, “I like to do nothing.”

He holds his hands in the shape of a bowl. “When a cup is full, nothing can be added to it. But if a cup is empty, you can put something new inside. So doing nothing is also very important sometimes.”

I leave feeling like I’d love to climb inside his inner world for a day or two, just to see what it looks like. And with the reminder that we don’t necessarily always need to understand something in order to appreciate the beauty in it.

For the latest news and upcoming performance schedule visit the official Sankaijuku website.

Updated On November 28, 2021