Kakunodate’s late-summer matsuri is a festival that begins with grace and ends with a celebration of a community’s fierce fighting spirit.

It starts off as a parade, a procession of floats and music. Young girls in kimono stand on the hikiyama floats, performing the slow, graceful moves of old dances of the North. Stepping lightly on the small stage at the front of the float, the dancers move to the melody of flutes and the rhythm of the drums. On its own, the music feels energetic, almost raucous. Channeled through the movements on stage though, the sound becomes more controlled, refined and subdued. It is the kind of scene that makes one understand how the idea of Akita bijin—Akita beauties—began. Outdated as the idea may seem today, the restraint and grace of the dancers seem to reflect an important part of Kakunodate’s history and tradition that the festival is trying to preserve. The focus now though is on understated elegance—the beauty of movement and performance are far more valued than a pretty face.

On September 7, each of Kakunodate’s neighborhoods unveils its long hikiyama float. Pulled by men, women, and children—some barely tall enough to hold the ropes—the groups make their way through the streets of Kakunodate’s historic town. At the center of each seven-ton wooden cart is a diorama, some with regal samurai figures, others with flashy warriors straight out of a kabuki drama. The more elaborate are topped with monsters and dragons from stories long ago. But unlike many of Tohoku’s more famous festivals like Aomori’s Nebuta Matsuri, the dioramas here are only a small part of the float. First and foremost, the Kakunodate Matsuri is a performance. Nearly half the float is made up of a stage at the front. On its way to Kakunodate’s Shinmei Shrine, each float will make numerous stops to perform for spectators and judges. The float’s two groups of dancers—one of young women, the other children—take turns performing as the float bearers have a seat on the ground to watch and cheer them on. The following day, there is more dancing and music as the floats parade through the streets again. Floats that meet in the street negotiate for the right of way, with one team laboriously navigating their float to let the other pass. The energy is festive and lively, but decidedly peaceful, even courteous.

For the first two days, it would be easy to think that the Kakunodate Matsuri is an exception to Japan’s bravado-filled festivals, with each neighborhood trying to out “macho” the others. And for nearly two and a half days it is. But on the final day of the festival things begin to change. The first thing one notices is that, after two days of being the focus of the festival, the dancers have left the stage. The next is that children are no longer pulling the floats. Mostly though, the energy is different. Without the need to accompany the grace of the dancers, the music and chanting takes on a harsher edge. It is as if a painstakingly developed tradition of arts and culture has been cast aside, revealing something much more basic, but beautiful in its own way. While the first two days of the festival preserve 350 years of tradition, the final night brings out feelings that are much, much older.

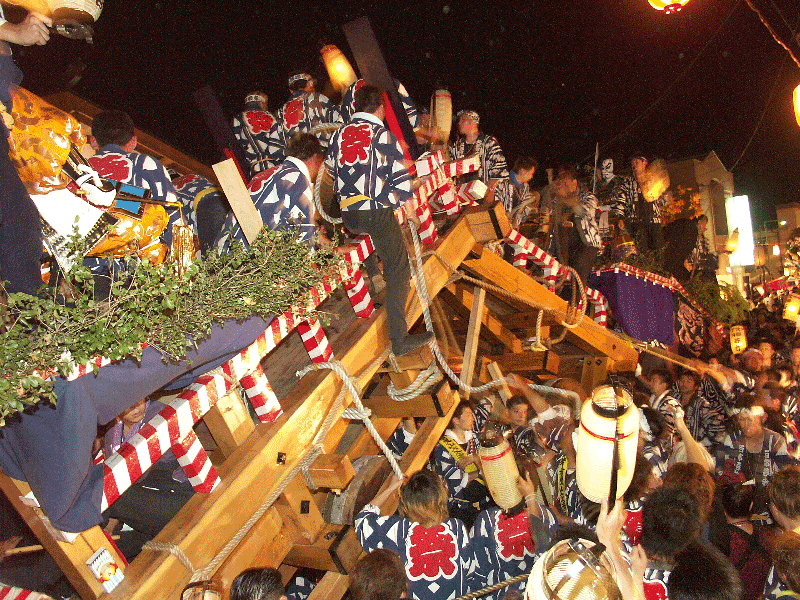

September 9, the final night of the festival, is the night of hikiyama butsuke – the battle of the floats. Hikiyama Butsuke is not an organized challenge; it is much more organic and primal than that. As the evening wears on, and floats meet in the street, negotiations for right of way become strained. When discussions break down, when neither team is willing to give way, they battle. After minutes of chanting, waving lanterns and posturing, the collision is swift. The two heavy floats ram into each other at speed, the front ends colliding and lifting into the air. Like a samurai duel of old, the build up draws out the tension, and the deciding blow comes in the blink of an eye. After untangling the floats, the victor can proceed, the loser having to turn and retreat. Through the night the hikiyama teams roam the streets, challenging and smashing into one another, cheers and the dull crack of collisions echoing through Kakunodate’s old samurai town.

Throughout the festival—both its graceful beginnings and wild climax—it is surprising how young the Kakunodate Matsuri feels. It is not just the dancers. Walking the streets during the festival, one sees float bearers, musicians, and onlookers of all ages. The number of school-aged children and teenagers makes one wonder if schools simply close for the festival. It is clear how important the event is to the whole community, and how it brings the town together today, in a celebration of its feudal past. In a time when so many people leave home for the big city, fewer children are born, and many towns are left with increasingly aging populations, Kakunodate has managed to do more than just preserve a tradition. It has made it a vibrant, relevant part of life for the community. It is something that those of us in the big city, with so many festivals seemingly focused on spectators rather than community, would do well to experience.

Seeing the Kakunodate Matsuri

The Kakunodate Matsuri takes place September 7–9 every year. Kakunodate Station is on the Akita Shinkansen Line, just 3 hours from Tokyo. The town itself, one of Japan’s many “little Kyotos,” has a charming historic neighborhood with beautifully preserved samurai manors, some of which have stood throughout Kakunodate’s 390-year history.

Sponsored Post

Updated On July 19, 2017