Queerness and gender fluidity permeate the landscape of Japanese culture, from BL manga to onnagata in Kabuki theater (male actors who play female roles). Additionally, sexual acts among males were common in ancient Japan and a major cultural feature in the Edo period. Japan was open-minded and even, in some cases, enthusiastic about same-sex relations up until Japan opened its borders in 1859, when Japan began to adopt repressive, Victorian-era attitudes towards sexuality in response to Western influence. Though Japan’s current political stance on queerness leaves much to be desired, Japan has a surprisingly rich history colored by a generally positive outlook on sex and sexuality.

From sex between male monks to 17th century erotica, Japan’s queer history might surprise you.

5. Buddhist Monks Tolerated Homosexual Relations

In general, attitudes in early Japan towards sexuality were free and permissive. As Louis Crompton notes in Homosexuality and Civilization, “Shintoism… had no special code of morals and seems to have regarded sex as a natural phenomenon to be enjoyed with few inhibitions.” When Buddhism arrived in Japan in the seventh century, it did so against the background of these cultural norms.

For Buddhist monks, who vowed a life of celibacy in order to reach enlightenment, sexual acts in general were considered off-limits. However, homosexual sex was considered the lesser of evils. In Buddhism, women were considered to be inherently more sinful than men; by partaking in heterosexual sex, monks were considered to be defiling themselves, whereas homosexual sex was more likely to be thought of as a lapse in judgment. Especially because monks would train in isolated monasteries for several years, a little sodomy was, they supposed, bound to happen.

Crompton quotes an account from a Jesuit priest from Portugal, who arrived in Japan in the 1540s; when he visited a Zen monastery in Hakata, he was shocked to find that “the abominable vice against nature is so popular that they practice it without any feeling of shame.” Another missionary who visited Japan between 1579 and 1603 wrote that male-male relationships were “regarded so lightly that both the boys and the men who consort with them brag and talk about it openly without trying to cover it up. This is because the [priests] teach that not only is it not a sin but that it is even something quite natural and virtuous.”

4. Many Powerful Figures in Feudal Japan had Young, “Beloved Retainers”

Not unlike ancient Greece, where young boys “apprenticed” with older men, feudal Japan had a system called nanshoku. The term translates to “male colors” or “male desire,” and this practice was actually imported from China. Many samurai-class sons were sent to Buddhist monasteries to be mentored by an older monk. The younger acolyte would then learn from, and often partake in a sexual relationship with, their mentor. Gary Leupp in Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan describes nanshoku relationships as a “brotherhood contract,” and the partnership was meant to be exclusive and mutually beneficial.

This culture of nanshoku expanded outside of monasteries, where it was called wakashudo, or “the way of young men.” Buddhist education, coupled with the fact that there were far more men than women in samurai-governed cities, made for a lot of homosexual interplay. As the famous poet Saikaku Ihara famously said, “[Edo] was a city of bachelors … not unlike the monasteries of Mt. Koya.”

3. “Mentors” Included Takeda Shingen, Tokugawa Ieyasu, Oda Nobunaga and Miyamoto Musashi

Just to name a few. As wakashudo became common among the samurai class, the term popped up in literature, often with ties to notable figures. Leupp compiled a list of over 20 powerful figures that were mentioned in the context of wakashudo mentorship.

Homosexual sex during this period of feudal Japan was also an assertion of power and dominance, with the older partner taking on the dominant role. As sexuality researcher Georgie Williams argues, gender may not have even been the primary framework through which these relationships were understood: “In Japan’s Edo period, one’s age was often a highly important factor in how the dynamic of a relationship was established, as well as social influence and authority.” And although a modern read on these wakashudo relationships can romanticize a full-on gay relationship between these famous historical figures and their vassals, many of these figures, especially daimyo and shogun who had to continue their bloodline, also had wives and concubines.

2. Male Prostitution was Commonplace in Japan Until the 19th century

Wakashudo also trickled into the middle class, with merchants taking on servant boys and apprentices. At the same time, the samurai class grew poorer and no longer able to afford full-time apprentices, and the bourgeoisie became more prominent. This made wakashudo untenable for many, and increased the demand for both male and female sex workers. Male sex work was also seen in the theaters, where kabuki actors who played female roles (onnagata) would have many admirers who paid to bed them.

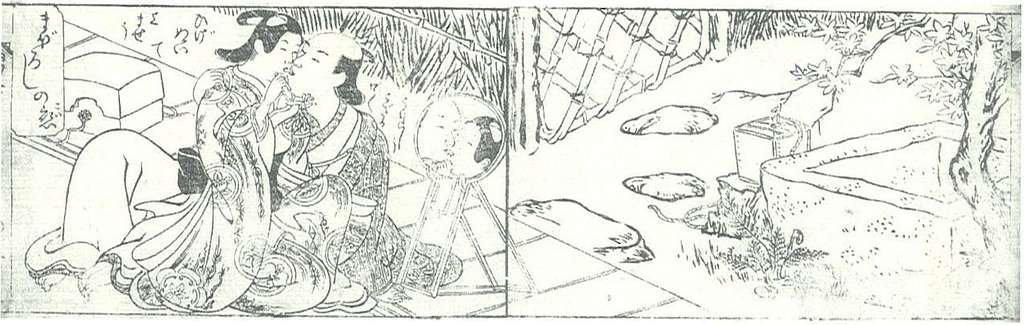

Ishigami, Aki (2015). Nihon no shunga, ehon kenkyu

1. Male Love was a Common, Widely Respected Theme in Art and Literature

In the indulgent time of the “floating world,” Edo was inundated with pleasure-seekers and art surrounding pleasure. Ihara Saikaku wrote Nanshoku Okagami (The Great Mirror of Male Love), a compilation of forty stories about the romantic relationships of samurai, monks and kabuki actors. The book is fiction, but paints an astoundingly vivid depiction of the extravagant and erotic lifestyles, including dramatic scenes of male lovers committing revenge killing or love suicides to escape a world in which they cannot be together.

Related Posts

- TW Queer Japan: A Quick History of Japan’s LGBTQ Icons

- TW Queer Japan: An Interview with the Vogue Artists of Japan

- Visit Japan: Tips for LGBTQ Travelers

Updated On April 15, 2024