“I’m not a BDSM maniac” is among the first things Hajime Kinoko tells me when we sit down to chat in his studio in central Tokyo. That is what many people might immediately assume, given that he specializes in shibari – in other words, Japanese rope bondage.

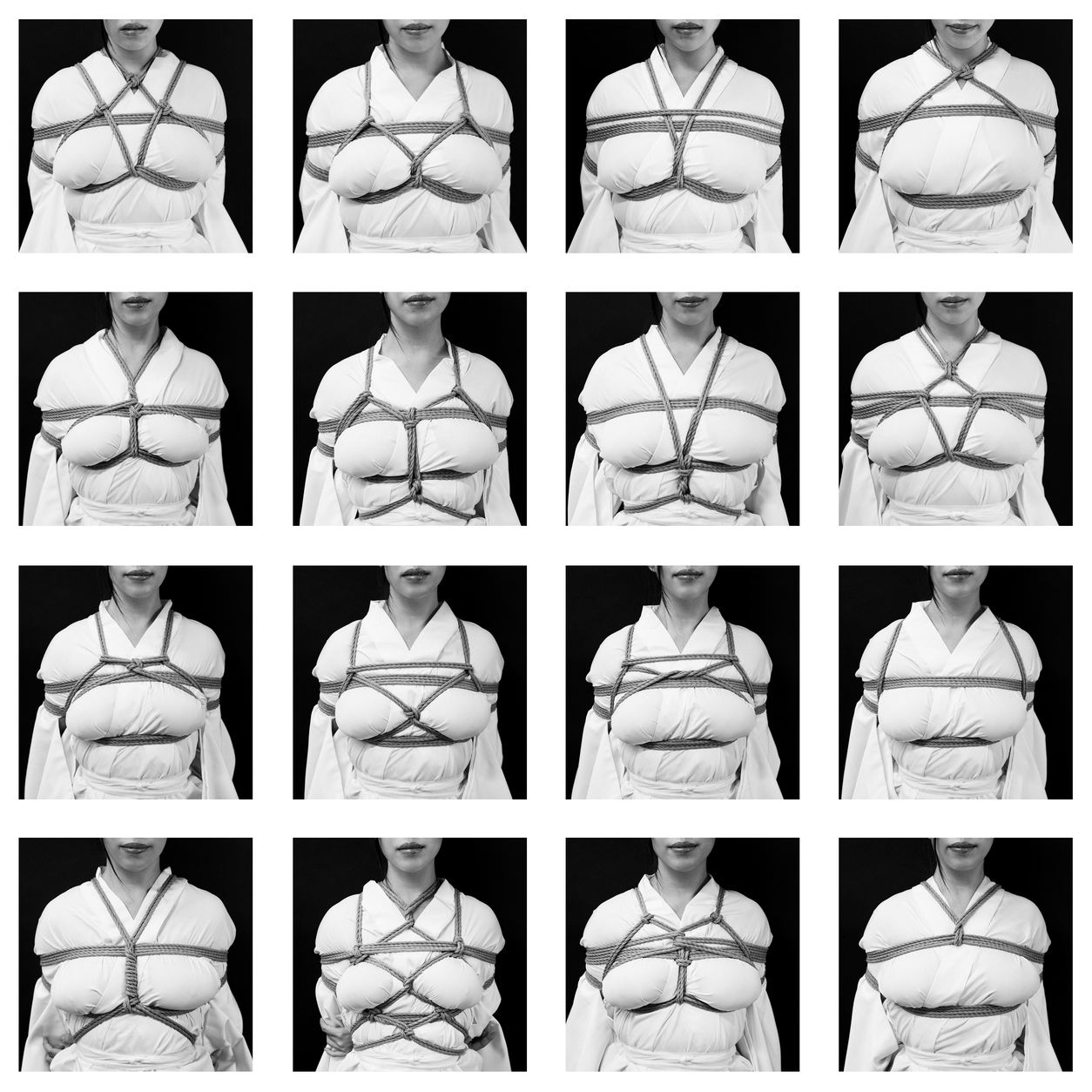

Shibari has always been done under the comfortable cover of darkness and behind closed doors. The eroticism of this tying technique thrives in privacy, while its criminal-restraining origins tinge it with some shame and guilt. Shibari is by no means secret, but it is whispered about sensually, practiced out of sight in windowless velvety or tatami rooms. Unless it is the kind performed by Kinoko. He dresses up shibari in its best outfit and takes it out in the sunlight for a walk.

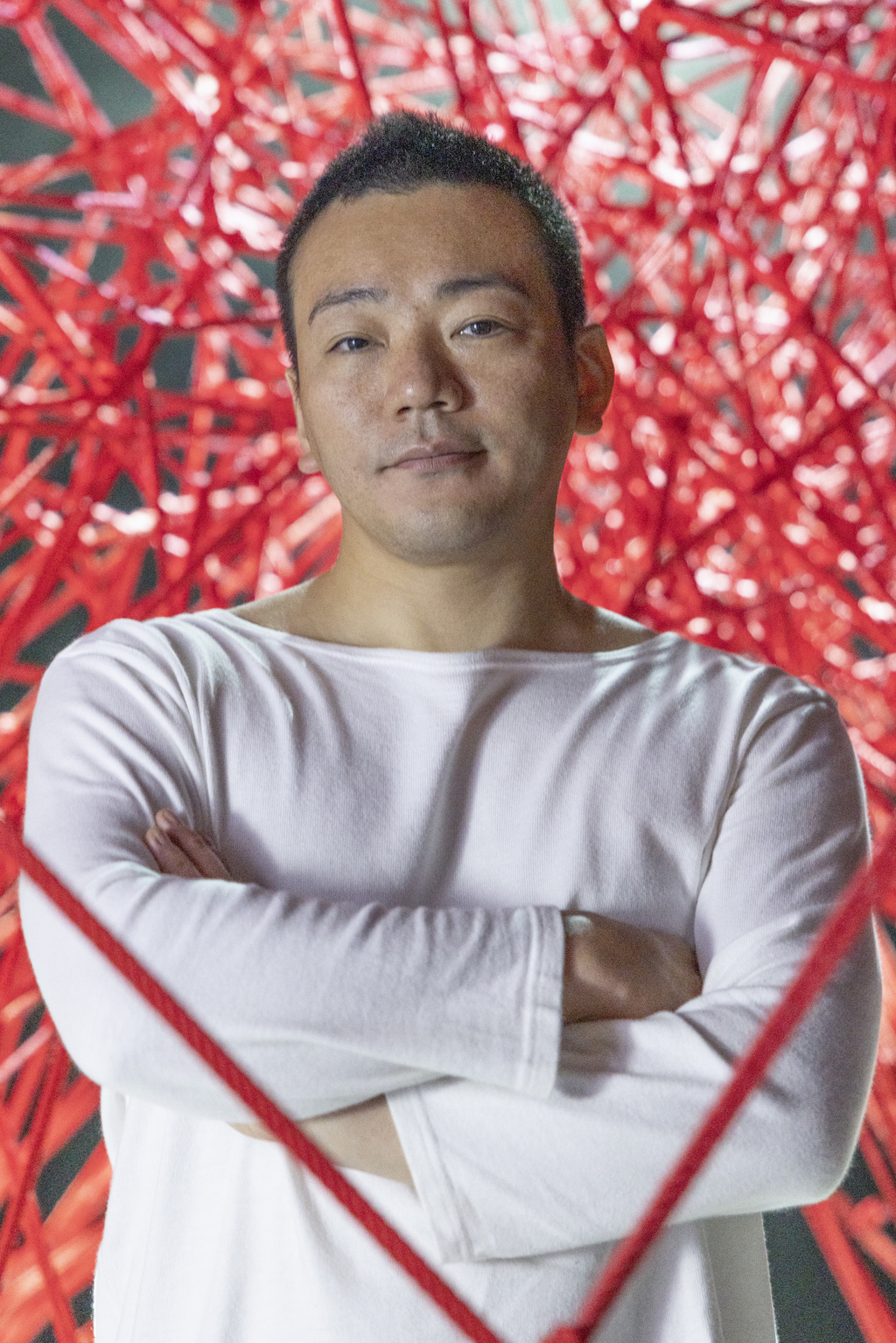

Hajime Kinoko

“Shibari is about connection,” Kinoko tells me. He explains that when tying someone, it’s not only about capturing or binding. That is the origin of the practice, but Kinoko goes well beyond that aspect. His shibari is a connection between him and the model, both a performance and an art sculpture.

“I create lines like those created by nature, and [they] only exist between the model and me,” his artist statement reads.

The word for Japanese rope bondage itself is a bit of a cross-cultural, cross-lingual tangle. In the West, the Japanese word “shibari,” simply meaning “to tie, to restrain,” has been widely adopted since the 1990s, while in Japan, there’s also “kinpaku,” which means “tight binding.” Many use these words interchangeably, but Kinoko prefers “shibari” for his artwork, saying “kinpaku” is more about the emotional exchange in bondage sessions. He also loves the word “musubu” because it is a soft, beautiful word that means “connection” and “intertwining.”

From invisible bonds between atoms to the imagined pathways between stars that form constellations, everything in this universe consists of ties, twists, bonds and lines upon lines drawn between everything. This is what becomes clear when we sit down to unravel Kinoko’s history with shibari.

Connections and Ties to the Shibari Scene

Kinoko happened to get into shibari in 2001, coincidentally with the start of the new millennium. He didn’t plan, however, to usher in a new era of Japanese shibari too. He began casually, prompted by his girlfriend at the time. In the decade that followed, he was guided by several famous teachers in the bondage community in Tokyo — namely, the late great master Haruki Yukimura, Mistress Kanna, and Akechi Denki, who was holding workshops at the fetish bar that Kinoko was managing.

After doing shibari in Tokyo’s nightclubs and niche events for a couple of years, Kinoko burst onto the mainstream stage with his performance at Fuji Rock Festival in 2009. The following year, his first solo exhibition titled “The young woman and string” was held in Harajuku, heralding his work as a photographer and an artist. He says this is when he also began drawing international attention, holding workshops abroad, appearing in a documentary for Vice and creating a rope installation for the Diesel store in Tokyo. The brands and the media he has worked with since are too many to list here.

The master shibari artist stands out from the crowd with his inventiveness, creative twists and out-of-the-box thinking. Around 2011, he invented cyber shibari as a brilliant blend of traditional bondage and entertainment that was best received by the music and party scene. The traditionally brown or red ropes are replaced with ones of neon colors, creating close to an optical illusion of an independent floating ropework over a dark, mysterious silhouette. It was a successful break from the erotic nature of shibari, and it underlined Kinoko’s pursuits in tying people and objects to form a bond, not bondage. By 2016, Kinoko was performing cyber shibari to tie up the likes of Ayabambi, a duo that was part of Madonna’s backup dancers.

Nowadays, however, he has moved away from the club scene, dedicating most of his time to classic shibari and creating art with it. In the last few years, he has been exhibiting at various galleries and at the annual Tokyo Art Fair.

Connecting With the Surrounding World

Aside from people of any gender, Kinoko ties objects too — from vases and roses to sections of Aokigahara, a forest notorious for the high number of suicides committed there. He rode in to our interview on a motorcycle, and it too had at one point been tangled in his art.

“I’ve tied this motorcycle and a model on it, and suspended them from the ceiling,” he tells me.

His most recent headline-grabbing project was when he tied the whole building of the StandBy Gallery in Harajuku in May this year. The endeavor took days and dozens of helpers, cranes and even models tied up and attached to the building. It all culminated in never-before-seen sharp-edged raw concrete roped in bright red knots. Within the installation period, there was a 15-minute performance with clothed models, tied artfully without accentuating sexualized body parts and leaving their hands free to move.

For Kinoko, red is a color symbolic of connection. He tells me that red expresses mothers, ancestors, nature, peers, DNA, the future and connections between hearts.

“I use red rope to emphasize ‘connections’ such as blood or fate, which is expressed in the Japanese language as ‘the red string of fate,’” he explains.

Kinoko matches the rope to his subject. The next building he tied was a white cocoon-like structure named The Natural Ellipse, considered an architectural gem in its own right. To match the cool exterior and its uniqueness, Kinoko opted to tie with blue ropes.

“I am actually closer to an artisan, like a chef,” Kinoko says, “and my models and ropes are like ingredients. I match whatever works best for the desired art result,” he concludes.

The Natural Ellipse shibari art installation started in September and is still ongoing at the time of writing with its end date yet to be decided.

Tying Bridges to the Future

It’s safe to say that the shibari master will never tire of experimenting and inventing. He’s now making augmented reality shibari art that is sold as NFTs (non-fungible tokens). He frequently holds events, trains teachers and gives classes in his Tokyo studio, as well as traveling internationally to teach shibari. He just came back from a stint in Italy and is already booked for events around Europe in the near future.

Kinoko shares that his international following has grown to be bigger than his Japanese one. He doesn’t know the real reason, but his best guess is that foreigners engage with shibari without any cultural baggage. They can approach it solely with curiosity and appreciate its artistry. He also notes that his target audience has always been wider than just the bondage fans. He brings up pole dancing or drag, arts that used to also be done mostly away from the eyes of the public, but have recently stepped into the limelight and become more accepted.

“I want shibari to not only be erotic and fetishist, but more artistic and fashionable. I want to change the perception of shibari,” he says.

These are not just whispered wishes. Kinoko has already taken shibari out of the Tokyo fetish clubs and to the music scene, to art galleries and out in daylight, covering whole buildings. As his recent Harajuku tie-up demonstrated to an ever wider audience, he has devised a different, non-sexualized shibari for his public performances. His shibari is a web, a crafty creation showcasing the beauty of both the subject/object and the rope. And ultimately, it showcases a traditional Japanese craft that he hopes his fellow Japanese people can take more pride in instead of severing their cultural ties to it.

Photos by Hajime Kinoko. Follow Kinoko on Instagram.