This article appeared in Made in Japan Vol. 4.

To read the entire issue, click here.

It’s a Friday evening in Koenji. Swaths of workers pour out of the station and cross the road while the sound of an acoustic guitar washes through the warm air. Young groups begin gathering noisily by a saxophonist, as a skateboarder tries to pull off a trick but loses his footing. Someone is shouting in the distance; the passing salarymen don’t bat an eyelid.

A free-spirited neighborhood, Koenji was the birthplace of the Japanese punk scene and continues to attract generations of artists and musicians with its streets of indie stores and underground shows. Its small-town feel is the result of evading the creeping redevelopment seen elsewhere (for now at least), due in part to the JR Chuo Line only stopping there periodically, as well as a strong anti-gentrification sentiment from locals. Guidebooks often compare it to the hip neighborhood Shimokitazawa, thanks to the streets of vintage stores open during the day, but nighttime is when Koenji really comes to life.

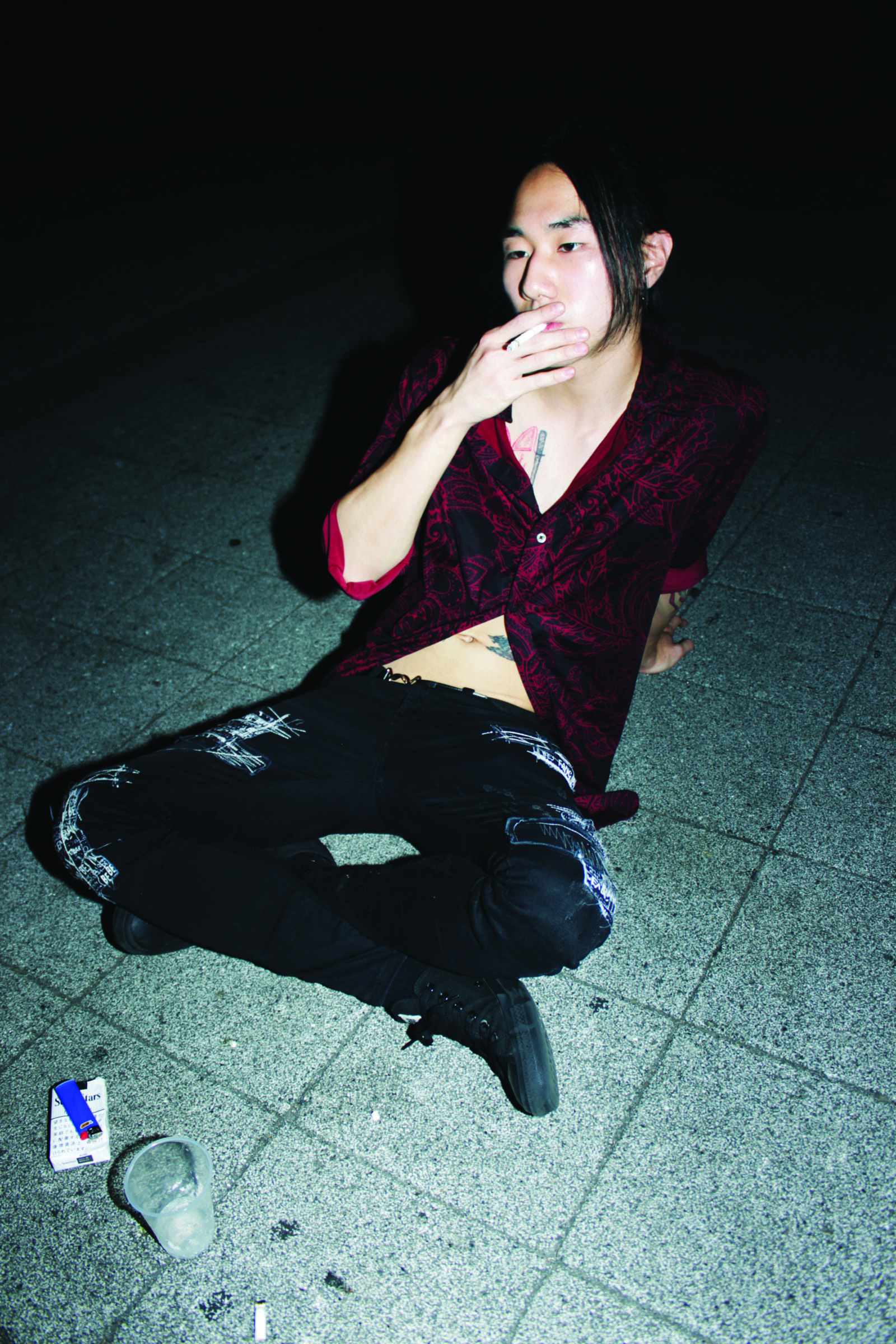

Photographer Lilise agrees, and last year she set up the Instagram account “Koenji Fashion Snap” to capture the area’s unique and chaotic effervescence. Typically taken during the night and drenched in flash, Lilise’s shots capture the buzz of DIY culture like an after-hours lovechild of Fruits magazine and an indie sleaze-era house party. Yet despite obvious nods to Japan’s rich legacy of street fashion photography, her shots feel fresh.

At a time of over-polished feeds and the meme-ish “irony” of high-fashion houses, the informality of Lilise’s subjects brings a real kind of magic: modern-feeling photography that takes the time to hang out. Living locally, I caught up with her to discuss fashion, subculture and late-night serendipity.

Full Interview with Koenji Fashion Photographer Lilise

What inspired you to begin documenting Koenji’s street fashion?

I was sitting outside listening to a street musician late one night, when a guy next to me began talking about how Koenji surprisingly doesn’t have a dedicated street fashion photography account. I thought this was such a great idea that I jumped on my friend’s bike, grabbed my camera and started taking photos. It was 4 a.m.

Your late-night fashion shots stand out from other street style accounts. Why do you choose to shoot at night?

Koenji has a lively street culture at night, where people sit around wearing their favorite fashions while chatting and drinking with strangers. Spontaneous encounters happen and a certain energy comes to life, so I look forward to shooting during these late and early hours. There’s an area outside Koenji Station where people of all ages, genders and nationalities gather just to hang out. And while shooting in this laid-back environment, I’ll often share a drink with the people I photograph. This helps to build an equal and more intimate relationship, allowing me to capture their natural selves.

What kind of person attracts or excites you as a good subject? What do you think makes a good outfit?

I look for people who have intriguing items — whether it’s something remade, self-made, creatively accessorized or inherited from family. Fashion that expresses an individual’s uniqueness excites me.

Do you have any photographic or artistic influences?

On the first evening I started, I took a copy of Fruits magazine along with my camera, thinking, “This can be like the midnight version of Fruits!” I didn’t read it in real-time during the 90s, but I appreciate its legacy. Growing up, I read every issue of the Japanese edition of Elle Girl. Unlike other fashion magazines at the time, the clothes in Elle Girl shoots were sometimes partially

obscured or had blurry photos, yet the magazine managed to capture the essence and atmosphere of fashion completely. I loved the commitment to fashion that shone through in Elle Girl’s photography and design.

What do you think the future of street fashion will be?

Looking back at how street fashion has evolved, many areas and streets were tied to their associated styles, and there was a need for common codes and identities that were tied to those places. Koenji’s “rotary” (the paved area outside of the station) functions as a plaza rather than just a street, becoming a place where various cultures gather and mix, so it’s much freer.

Despite current fashion styles and trends becoming more shallow and focusing on consumption, young people still seek accidental encounters with others, and have the power to discover things on their own. I think as long as people possess this want, street fashion will continue to find new meanings.

Follow Koenji Fashion Snap on Instagram here.

Related Posts

- Lee Chapman’s Quietly Profound Photos of Tokyo Life

- Photographer Herbie Yamaguchi Has a Message for You: Stay Punk!

- Tokyo Minimalism: Maki Shinohara Photographs the Calm Side of the Capital

Updated On August 6, 2024