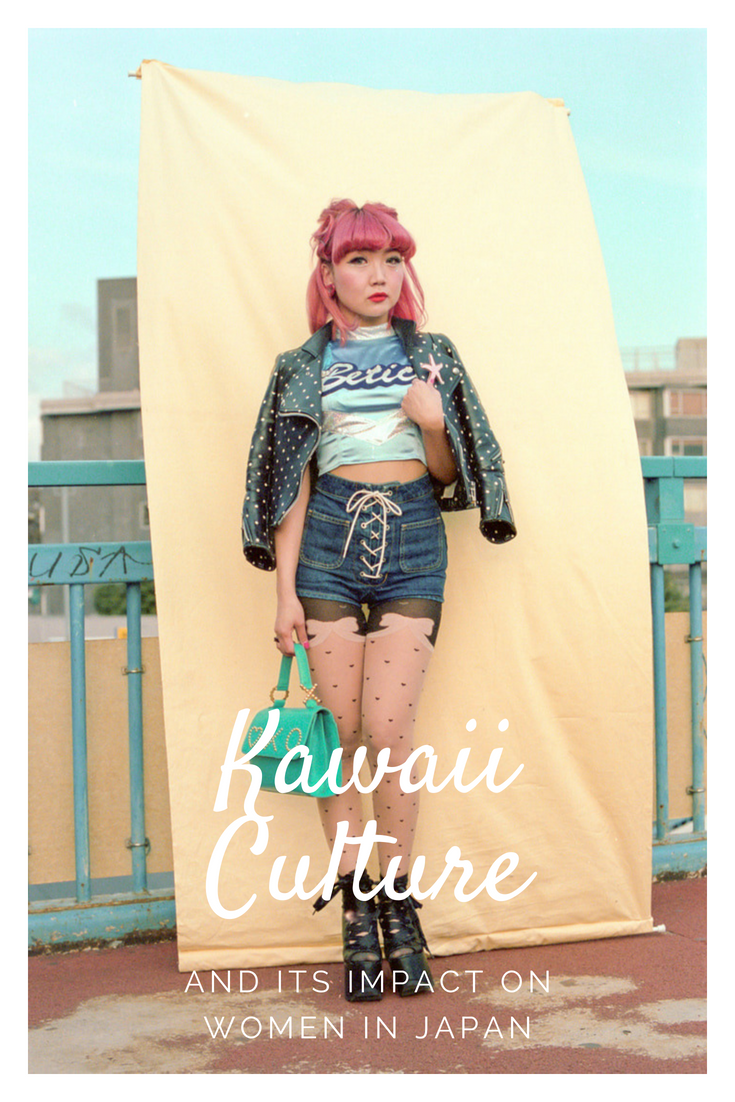

From frilly Lolita fashion and schoolgirl uniforms to voluptuous anime beauties and virginal pop idols, the discourse between Japan’s obsession with female “cuteness” and its outdated (but prevailing) lack of gender equality is often overlooked. Tokyo-based Austrian photographer Sybilla Patrizia’s “Strawberry Jam” series is an exploration of female representation, expectations and self-expression in contemporary Japanese culture, offering a deeper look at people’s real-life connections to “cute,” and inviting viewers to expand their perspectives.

Many Japanese women’s kawaii aspirations have long been dictated by popular culture and the media in a male-dominated society. Are those pastel colors, soft high-pitched voices, and artificially dewy eyes really what women want for themselves? Or is “performative cuteness” just a way to fit in and keep up appearances? Can kawaii ever be empowering? The photographer sits down with TW to discuss.

When did you begin working on this project and how did it come about?

This was a project for my university graduation while I was studying in London, and I was working on it for around two years in total. I knew I wanted to do something related to Japan, and pop culture; something modern. I was researching anime culture, female culture, kyabakura [host and hostess clubs], sex clubs, all this stuff that’s happening in Japan, and then I realized that what many people don’t talk much about is the representation of women in Japan versus in the West. I wanted to do something around that. I’m a woman and I’m young, so I felt I could relate to the subjects and the culture. I came to Japan for about two months to take the photographs, and then held an exhibition in London and produced a handmade book for the project. I held another exhibition of the series in Tokyo at the Austrian Embassy in March this year.

What do you find shocking about the representation of women in Japan?

I didn’t notice it so much the first couple of times I came here, maybe because I was younger, but later it just kind of hit me. It’s not just about women in Japan, but also the Japanese animation style – women with huge boobs, super sexualized … you think, “Oh my God, I watched this as a child? This is ridiculous!” When I’m looking at myself, my friends or women in most Western countries, it seems women are seeking to be empowered and strong, not so much cute – that’s more something we do when we’re younger. Coming here, it’s actually crazy, there’s such a huge difference in how many women dress, act and talk.

I interviewed some friends to get an idea of what the situation is like for women here, including within the work culture. I was asking them questions like, “Do you feel women are discriminated against?” and they were like, “You know, you’re right, it’s kind of fucked up, and maybe we shouldn’t do this … But it’s normal for us, and also we’re in this culture and we don’t want to stand out too much.”

“I realized that what many people don’t talk much about is the representation of women in Japan versus in the West”

I think a lot of the topics in my work are such everyday topics for many Japanese people that perhaps they’ve become normalized. As foreigners we often have a fresh view on these things. If you look at how sexualized schoolgirls are in Japan, that can have a lot of negative consequences. And if it’s just normalized and not really talked about, it could be quite dangerous. We need to look at it from lots of different perspectives.

Japanese society has an inherent and widespread appreciation for cuteness; even businessmen like cute mascots. So what’s wrong with women being cute?

I guess what’s important to notice in the project, or generally, is that cuteness can take on lots of different forms. Some of the people in my project, from Harajuku fashion, dressing in Lolita or Decora style, for them it’s a form of empowerment, that’s who they are, and that’s who they want to be. When I look at them I think that’s amazing; they have no fear of showing who they are. I think that’s great and anything that empowers you is good. I wouldn’t want to take it away from them. I love cute things, too! I think as long as cuteness is not used to overpower certain groups of people, it’s something positive.

I think what’s more troublesome is how in mainstream Japanese culture, women are expected to be shyer, softer, not raise their voice, sound cute … I don’t know if that’s something they’re happy with or if that’s something they want. I know certainly some women want to be like that perhaps because they believe it makes them more attractive to men.

That’s one negative aspect about Japanese culture; there’s a strong sense that you need to match up to or perform according to what’s expected of you, and people maybe sometimes don’t feel empowered enough to stand up [against it]. If that means women feel like they have to lower themselves to please their boss or whatever, then that’s bad.

In an essay accompanying the project, you mention the notion of “performative cuteness.” Do you think women trying to be cute reinforces a gender imbalance?

Many foreigners also grow up in a culture where women are sexualized. We see certain images in the media and subconsciously try to copy or follow these. But I think the Japanese media landscape is quite different from the West – women here are often portrayed in this really cute way so that’s the way Japanese women grow up, and those are the ideals they try to emulate. I don’t know to what extent people in Japan analyze it, but I don’t think this type of culture has a negative image here. Generally I feel like social issues – such as female empowerment, how women are portrayed, or how the women themselves play into this role of having a lower social status – aren’t really discussed here. Although recently the #metoo movement has come to Japan, so I think it’s discussed more than it was a few years ago.

Often the stereotype of “weird Japan” can cause audiences overseas to misinterpret cute as sexual. How do you consider the Western gaze when you present your work?

Western cultures looking at non-Western cultures is always difficult. With Japan there’s this specific image that the media have created, and some Japanese media reinforce. From the Western perspective, we tend to try to see things according to the way we grew up, and that’s problematic because the world isn’t centered around a Eurocentric or American point of view. We sometimes go into a foreign culture thinking “This is so wrong!” or “This is so weird!” But why is it weird? Just because it’s different? We need to take a step back sometimes and re-evaluate our own values.

One of the issues addressed through my project is that the viewer might look at the images with this reinforced stereotypical image of Japan, especially if you just see the images without any context. So I tried to make a point of showing various perspectives of cute culture, because it’s not just black and white. Not all cute is sexual. And just because Japanese culture values cute more than the culture I come from, doesn’t make it necessarily bad. Personally, I like the fact that here you can like cute things without being judged for it; guys can say, “Oh this is cute!” and they’re not getting negative comments from other guys, whereas in other countries we have that Western macho thing. I feel that people who engage more with my work and read my text or hear me talk tend to understand it on a deeper level; they learn something new about Japanese culture. Of course, with art, not everyone will understand the message, and that’s okay, but we can try.

Having previously photographed Tibetan refugees in India and the Umbrella Protest in Hong Kong, you seem to be drawn to capturing social issues. Why is that?

As an artist it’s important to expose yourself to different cultures and countries. A lot of people in the Western world live in a bubble, and don’t want to expose themselves to things that are uncomfortable. But this is so important in order for people to grow and society to get better. I think if you create art, it needs to have a purpose, whatever the purpose may be. For me, I notice things that are happening in the world that might be wrong, and I think it’s important for other people to know about them too. As an artist, as a human being, I can’t disconnect the two, so I think what’s the point of doing the project or taking the photographs if I don’t have some greater purpose or greater message I want to convey? Even if it’s just pointing out small issues, it’s important to me to have that.

See more of Sybilla Patrizia’s work and read her essay on the “Strawberry Jam” project at www.sybillapatrizia.com

Updated On September 9, 2019