I will make my film!

That’s why I have dared

To enter this world of cinema

To show men, not to work for them!

Tazuko Sakane wrote these words in 1936 when she believed she was on the verge of forever changing the world of Japanese cinema. But somewhat appropriately for a poem titled “Intoxication,” Sakane’s declaration amounted to little more than wishful thinking. In the end her life had turned out almost the exact opposite of what she’d hoped.

Sakane in a (Controversial) Nutshell

The aspiring artist did end up making a motion picture, thus earning her the title of Japan’s first female director, but it was a story that the studio wanted to tell, not her. Worse yet, the critical response to it was as lukewarm as it was sexist, meaning she lost her position within the studio. It also led to her being relegated back to the position of an assistant to a male director. In other words, working for men.

Although, as an editor and script supervisor, Sakane was given a lot of freedom to experiment with the craft of filmmaking, which is evident in the many non-fiction movies she went on to make. Now, a lot of them were wartime propaganda as that was the only way for unfairly marginalized artists to continue making movies. However, that didn’t mean they weren’t without artistic merit. But, still they were wartime propaganda. And that’s a quick summary of the complicated legacy of Japan’s first female director.

Here’s a longer version:

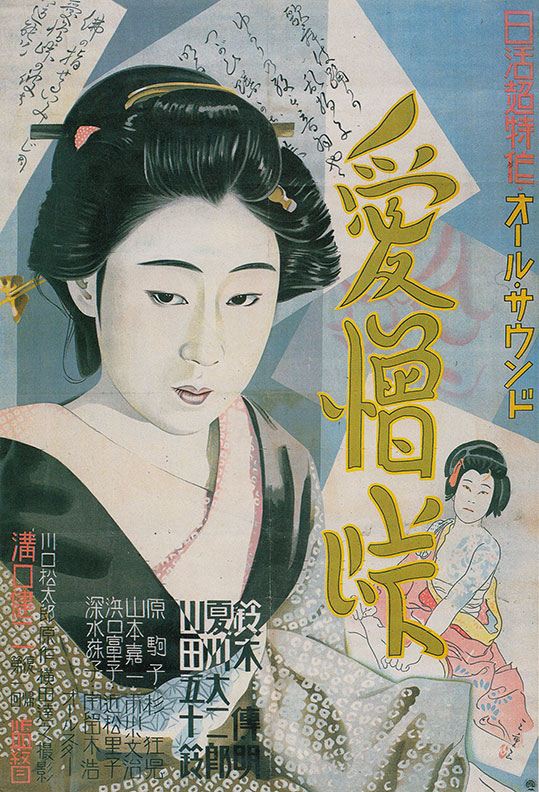

Poster for The Mountain Pass of Love and Hate (1934) for which Sakane was assistant director to Kenji Mizoguchi

A Woman Ahead of Her Time

Born in Kyoto to a well-off family, Sakane’s early life was characterized by a high degree of freedom seldom enjoyed by other women. For example, she was encouraged by her father to go to the cinema as often as she wanted and develop her interest in art. She even briefly studied English literature at college before her mother forced her to quit and arranged for her to get married. She went through with it, possibly to get her mother off her back, but then quickly got divorced and followed it up with something bordering on scandalous in those days: she got a job.

Her father helped her get hired as an assistant to Kenji Mizoguchi, one of the most influential figures in the history of Japanese cinema. He was known for his stories featuring complex female protagonists challenging social norms and fighting resiliently against a patriarchal society trying to crush them. Mizoguchi and Sakane quickly developed a rapport and the young woman became his disciple. She worked as an editor on his movies and even assisted him with directing at times. Throughout all this, Mizoguchi kept pushing various studios to let Sakane make her own films. Finally, one agreed.

Tripped at the Starting Gate

Sakane hoped that her debut film could be about female students reshaping the fabric of Japanese society. Instead, the Daiichi Eiga studio in Kyoto saddled her with a period drama about the doomed love between a geisha apprentice and a Buddhist acolyte. Hatsu Sugata (1936) is unfortunately now lost and all we have left from it is the promotional profile of Sakane that the studio put out before the premiere (which, for whatever reason, includes questions about the status of her virginity) and the reviews. According to critics, Sakane was imitating Mizoguchi’s style, the same one she herself helped develop as his editor. She also supposedly lacked “female sensibilities,” which, as men, they would know all about.

After Hatsu Sugata flopped, the studio lost faith in Sakane, if they ever had any. She subsequently went back to working as Mizoguchi’s assistant. And then World War II broke out.

From left to right, Shin Takehisa, Tazuko Sakane and Tokichi Ishimoto at Daiichi Eiga – Circa 1936

The Propaganda Work of Tazuko Sakane

Japan’s wartime period meant tightened censorship of movies. But it also increased the demand for filmmakers to make government propaganda films. In 1942, after years of being sidelined because of her gender, Sakane moved to Manchukuo, the puppet state created after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, to make “educational” films encouraging Japanese people to move out west. One of those movies, Brides of the Frontier (1943), is the only surviving directorial piece by Sakane. Although its goal was to get Japanese women to come over to Manchukuo and marry farmers, there’s real artistry to the film, like its splendidly-crafted pacing or its use of symbols showcasing Sakane’s mastery of the rule of “show, don’t tell.”

However, it’s hard to look past the fact that the movie was promoting colonialism. Sakane herself claimed that she had no political leanings, but that is a poor excuse. In her defense, after the fall of Manchukuo, Sakane stayed in China to help train a new generation of Chinese filmmakers. Sadly, she wouldn’t be shown that much respect back home.

Ukiyo-e print, “Women Embracing in a Green House”, Edo period, circa 1765-1770 – by Suzuki Harunobu

Forgotten Queer Icon?

After returning to Japan in 1946, Sakane could not get hired anywhere as a director and so went back to being Kenji Mizoguchi’s right-hand woman, fanning the decades-long rumors about there being something between the two. We have no historical source that would back this up, though. What we do have are clues to Sakane possibly being a part of the LGBTQ community, like her dressing up in male clothing. Some have tried to explain it away by her trying to fit into the male-dominated world of filmmaking but, for example, Kinuyo Tanaka, Japan’s second female director and Sakane’s contemporary, didn’t dress like a man. She ended up directing six motion pictures to Sakane’s one.

Also, besides her failed marriage, there are no records of her ever being involved, romantically or otherwise, with a man. Finally, Sakane did say on more than one occasion that one of her greatest inspirations was the German film Mädchen in Uniform (1931), one of the first depictions of lesbian relationships on film. Was Sakane gay? We can’t say for sure. It would be great if we could analyze her fiction work for clues but none have survived. So, for now, she must remain a pioneering mystery with a penchant for challenging social norms and a complicated legacy.