Japan’s ancient capital is loved as much for its nature as for its culture. The myriad of temples are revered for their stunning green gardens as much as they’re respected for their venerable history. Anyone sitting on the banks of the Kamo River flowing through Kyoto would agree that the city has maintained an enviable balance of the natural and the urban. Coincidentally, that is exactly where the fifth anthology of the Writers in Kyoto (WiK) had its al fresco book launch this May.

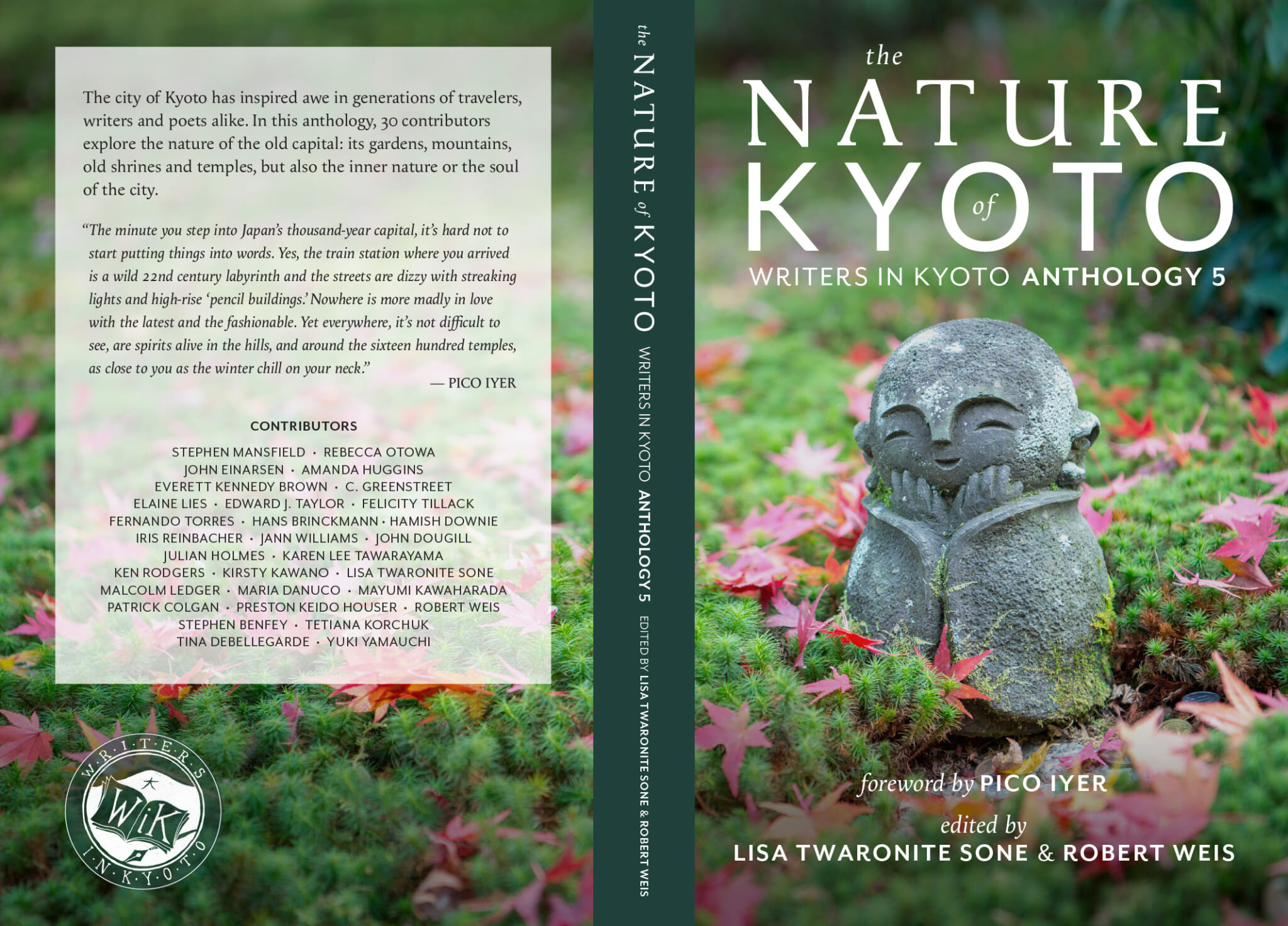

Coming out of a pandemic, I’d be remiss not to remark on the fact that so many of us turned to nature more than ever, whether it was the plant-buying craze, or the walks and picnics. WiK too have selected nature as a theme of their fifth anthology. This refers both to the physical nature around us, but also to the “inner nature,” or the spirit of the city. All the authors in the anthology either live in Kyoto or have some connection to the city. They have distilled their Kyoto experiences in prose and poetry. This anthology was edited by Lisa Twaronite Sone and Robert Weis, with Jann Williams as the anthology supervisor.

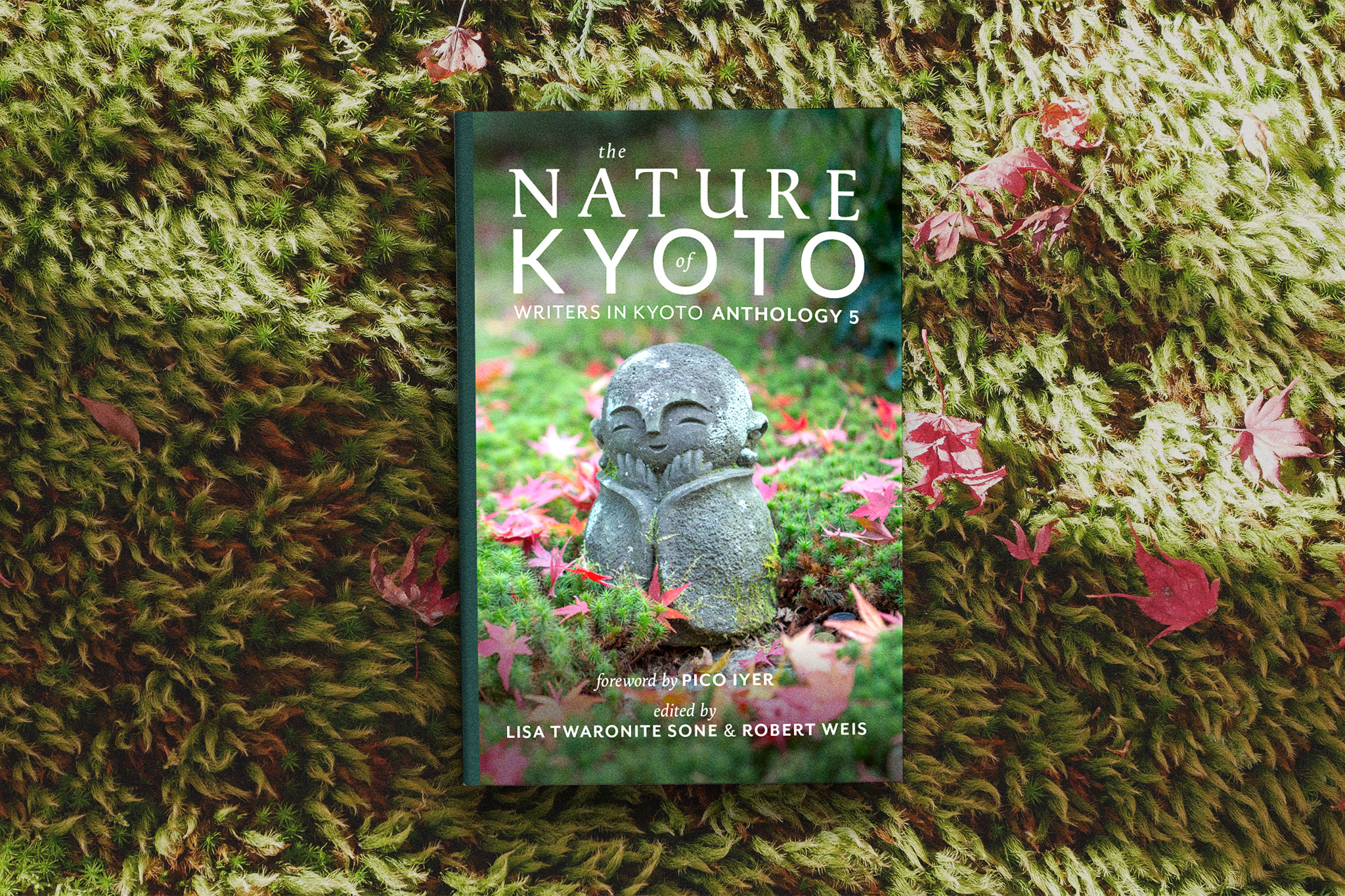

The Nature of Kyoto: Writers in Kyoto Anthology

Nature often escapes writers of the 21st century as we pick at the dystopian undertones of uber-capitalism, urban loneliness and mental illness. When it does make an appearance, it’s often to lament the lack of nature or its endangerment. As a Tokyo resident, I related to Stephen Mansfield’s essay, in which he juxtaposes Tokyo’s “demolition crews, chainlink fences, shuttered gaming halls” with Kyoto’s Zen destiny of being “predisposed to hosting the natural world.” This essay opens the anthology, as if welcoming readers from everywhere to Kyoto. It’s like a romantic longing for nature. For fair balance, the anthology closes with Yuki Yamauchi’s essay on wrestling with fear of nature and his visit to Sanzenin Temple.

The Nature of Kyoto anthology explores the different facets of nature. Besides Yamauchi, other writers also look at the dark side of it. This includes an essay by Fernando Torres titled “Nature is Trying to Kill You” and Edward J. Taylor‘s “Peeks on Danger.” Like the toothy fish in Ted Hughes’ poetry, stories like these remind us that nature is complicated.

Kamo River, Kyoto

On the lighter side, nature rules haiku with kigo (seasonal words), so it was enjoyable to read the “Keywords of Kyoto” haiku series by Mayumi Kawaharada. “Sudden Tsukimi” by C. Greenstreet, the winner of the 2022 Yamabuki Prize, shows the irresistible pull of nature that creates beautiful moments even in lonely situations. The delightful “Local News” by Ken Rodgers is all about returning to a life in nature.

Between enjoying nature and being scared of it, there are also works that remind us that nature shouldn’t be taken for granted. In the second story following Mansfield’s, Rebecca Otowa shows us that both Kyoto’s nature and culture are being threatened by urban development. Where the first writer sees an escape in Kyoto, the second shows us how it can all disappear in “The Pocket Garden.” Hamish Downie touches upon the changes, but is more optimistic in concluding “Kyoto doesn’t bend to the world — the world bends to Kyoto.” Towards the end of the anthology, the words of Kirsty Kawano embody the complicated coexistence of nature and human technology. She tells the ongoing story of a Shinto shrine’s survival efforts in “Nashinoki Shrine Makes Lifestyle Changes.” I’ll end with her words.

“The nature of a city with a long and rich history is that it knows time is always moving forward, and that we must move with it.”

About Writers in Kyoto

Writers in Kyoto (WiK) was started in 2015 by author John Dougill to be an informal and supportive space for writers living in the city. WiK counts over 70 members and hosts its own annual writing competition, the winners of which are also part of the anthology. See how to become a member here.

The Nature of Kyoto anthology is available for purchase online on Amazon.

Updated On June 19, 2023