Japan is a real literary hub for excellent crime writing. Keigo Higashino, Hideo Yokoyama, David Peace and Kaoru Takamura have all set the crime genre on fire over the years. However, it is the translated work of Natsuo Kirino that most intrigues me. She’s known for her female-led narratives often set to the background of important and often overlooked social issues facing Japan. The page-turning plots and grisly murders make Kirino, now in her 70s, one of Japan’s greatest literary exports. Sure, she’s not as experimental as Sayaka Murata or perhaps as incisive as Mieko Kawakami, but Kirino’s three major translated novels strike at the heart of the Japanese crime genre and the greatest pity is that only a handful of her many novels have ever been translated into English.

However, I often ask myself why do we read literature? Why is it important? These are questions that I routinely ask. And as an undergraduate and graduate student of literature, these questions and many others became more apparent and crucial as I grew older.

Time becomes more precious, so naturally the books you read become more selected. Books are now, for me, chosen to be easily read on a commute and can comfort and ease rather than challenge or probe. The 2,000-page B.S. Johnson novel or James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake that you always planned on reading is replaced by the new Bret Easton Ellis or Siri Hustvedt book. Not that these are easy reads per se, but easier than Samuel Beckett, Joyce or Shakespeare. And essentially, literature that you already know and trust will always be insightful and will comfort you no matter what.

PHOTO BY HAKAN NURAL ON UNSPLASH

Comfort reading for me over the last few years, to be honest, has become the spy novels of John le Carré, the beautiful work of Chinese American writer Yiyun Li, the output of Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh and the nonfictional gems of Geoff Dyer.

If I find myself delving into Japanese fiction, then Shusaku Endo or Banana Yoshimoto are usually my first ports of call. A few years ago, however, I became intrigued by the work of Natsuo Kirino. I’m not a crime “reader” really. The only crime books I usually read and suggest are Donna Tartt’s masterful The Secret History, Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley series and the Martin Beck novels by brilliant anarchist Swedish duo Per Wahlöö and Maj Sjöwall.

There’s something about reading Kirino, however, that really draws me into her world. Her three major novels that have been translated into English over the years are Real World, Out and Grotesque. Here we look at why these novels are important and why they set Kirino apart from her contemporaries.

Real World, translated by Philip Gabriel

Probably the most accessible and lightest perhaps, in terms of themes, Real World is the novel that I would start with when delving into the mind of Natsuo Kirino. A look into the world of high school students who are entrapped in the narrative of a murdered mother, Real World is very much of its time. It touches on a host of themes which haunt teenagers the world over.

James Smart in The Guardian wrote that it’s, “a telling portrait of a group whose life of cram schools and preoccupied parents leaves them distrustful of the adult world they are being groomed for. It rarely pauses for breath, scurrying from girl to girl through bland malls and pervert-haunted trains, its pages stained with unhappiness, frustration and moral uncertainty.”

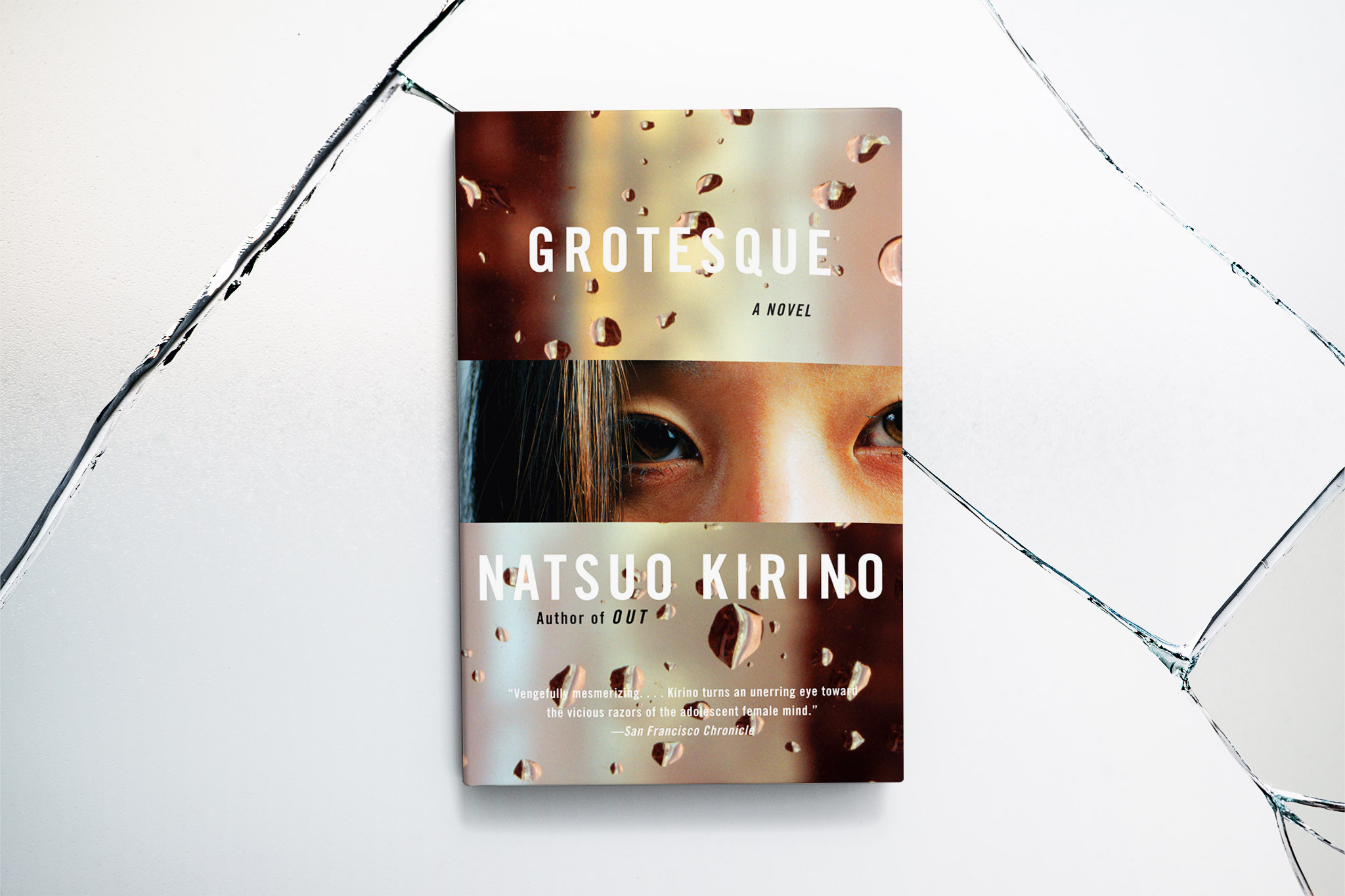

Grotesque, translated by Rebecca Copeland

Jam-packed with spite, hatred and vengeance, Kirino’s blockbuster work, released in the same year as Real World, Grotesque is a feminist-driven narrative in which two women are murdered and we, the readers, are taken inside the minds of one of the victim’s sister and former classmate of the other. The outrageously beautiful murdered sister and classmate are both sex workers and Kirino sets out her notion that acts of prostitution can also be considered acts of feminism, a device which was, in 2003, relatively provocative.

“My armor during the day was a flowing cape; at night it became Superman’s cape. By day, a businesswoman; by night, a whore. … I was capable of using both my brains and my body to make money. Ha!” It’s a fascinating and gripping piece of fiction which lingers and asks the reader to return to it for one more whirl into the mind of hatred and envy.

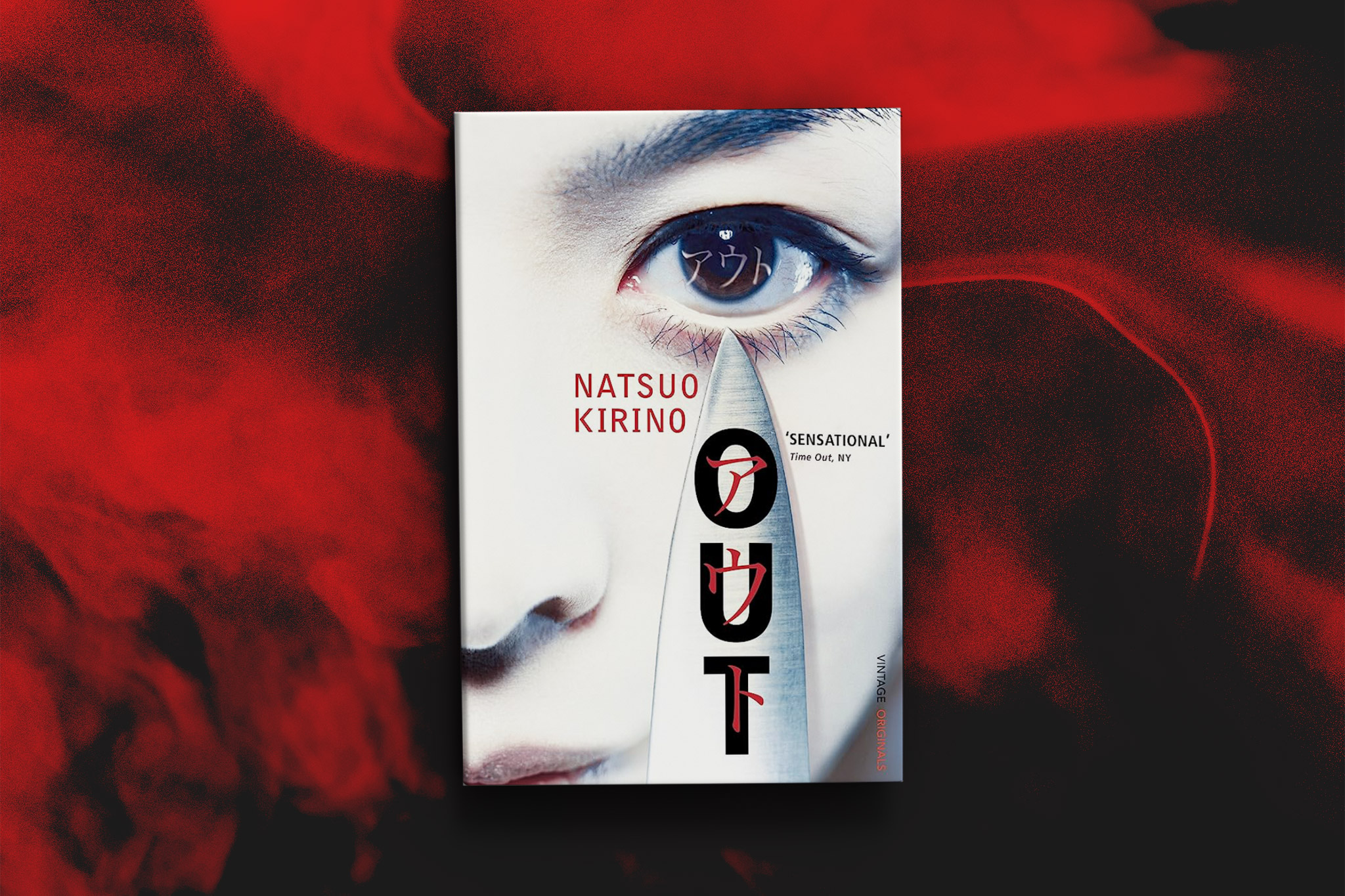

Out, translated by Stephen Snyder

Probably Kirino’s most loved and acclaimed novel is the superb Out. Adapted for film in 2002 (which can be enjoyed here on YouTube) starring Mieko Harada, Mitsuko Baisho, Shigeru Muroi and Naomi Nishida, Out is a gritty portrayal of friendship and murder with a background of domestic violence.

Interviewed in an article for Nippon.com, Kirino said, “If you’re writing about people who are being bullied and abused, people who are cut off from the mainstream, then inevitably you’ll be writing about women more often than not. The problems faced by women in contemporary society are sensitive and complex — so I always try to take care to make sure that I’m not treating the issues in a superficial way.” Out, with its narrative set in a bento factory, is claustrophobic, intense and hugely enjoyable and marked Kirino out as a real leader in the realms of Japanese crime writing.

More Japanese Literature

See our other bookish recommendations: